In Bihar, the channel between stardom and politics is organic

Bhojpuri stars wield an enviable emotional thrust

The rise of actor-politicians in Bihar unmasks the performative dimension of political culture

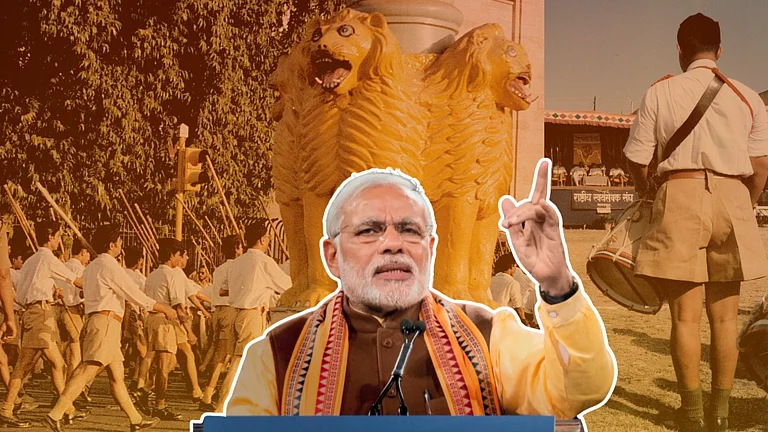

Theatre Of Power: Bihar’s Actor–Politicians And The Political Potency Of Stardom

On the grand stage of Bihar election 2025, acting, singing, and campaigning are no longer separate professions—they are overlapping performances within a shared economy of attention. It perfectly defines one of the strangest paradoxes of Indian democracy: that in Bihar, to be a politician often means to already know how to act.

In Bihar’s unruly theatre of politics, the boundary between performance and power collapses into spectacle. The state has consistently created space for a distinct kind of leadership which rises from the screen to the constituency. Manoj Tiwari, Ravi Kishan, Dinesh Lal Yadav “Nirahua,” Khesari Lal Yadav, Pawan Singh, Shatrughan Sinha and Kunal Singh exemplify this strange, magnetic intersection of cinema, celebrity, and governance. It perfectly defines one of the strangest paradoxes of Indian democracy: that in Bihar, to be a politician often means to already know how to act.

The turn from stardom to politics in Bihar is neither accidental nor spontaneous. Bhojpuri cinema, with its vast migrant audience spread across Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, Delhi, and the Gulf, has long been a cultural lifeline for those displaced from home. Its heroes are often working-class, romantic, earthy, and occasionally lawless, mirroring the very demographic that constitutes its fanbase. When they step into politics, this fan base organically transforms into their voter base, the emotional shorthand built through film and music naturally translating into political capital.

When Manoj Tiwari, once the “voice of Purvanchal,” joined the Bharatiya Janata Party, he carried with him a ready-made ecosystem of fans. Dinesh Lal Yadav “Nirahua,” who joined the BJP in 2019, built his political persona around the same archetype that made him famous: the underdog who takes on a corrupt system. Ravi Kishan, now a two-times BJP MP from Gorakhpur, embodies the same synthesis of entertainment and oratory, fusing his movie bravado with the rhetoric of Hindutva populism. Khesari Lal Yadav, one of Bhojpuri cinema’s biggest modern icons, formally joined the Rashtriya Janata Dal in October 2025, completing a symbolic symmetry in which each major party now flaunts a film star or singer as its cultural mascot.

Why does acting sit so comfortably beside gangsterhood and governance here? Because Bihar’s political modernity was forged amid the social framework of criminality. Since the 1980s, local strongmen and caste-based enforcers have controlled votes through visibility and fear. In such an environment, fame itself becomes protection. Both the actor and the gangster operate through reputation, charisma, and fear. The politician, especially in Bihar’s populist grammar, borrows from both. An actor-turned-politician can therefore enact toughness and benevolence in the same gesture: motivating people at a rally, threatening an opponent and simultaneously singing a folk song about honor. Theatricality here thus becomes a form of governance.

Bhojpuri cinema already romanticizes this archetype. A leader who can threaten and charm in the same breath is the perfect populist product. Bihar’s rallies often resemble concerts: fireworks, dhol beats, film dialogues, and crowd chants. Music, too, is political infrastructure. Each actor controls a mini-industry of content creation: YouTube channels, music labels, stage-show circuits, and fan clubs. During campaigns, these become multimedia propaganda networks. Bhojpuri YouTube channels often blur the line between entertainment and political messaging. Manoj Tiwari’s “Rinkiya ke Papa,” once a household tune, became a nostalgia weapon at BJP rallies. Nirahua’s campaign number “Nirahua Hindustani” mixed nationalism with Bhojpuri pride, while Pawan Singh’s stage shows, often held at party events, turned cultural fandom into political currency.

Behind the camaraderie of these stars lies a competitive fraternity. Rival singers have been seen sharing stages during elections, only to release diss tracks weeks later. The friendships between Tiwari and Kishan, or the soft public rivalry between Khesari Lal and Nirahua, are rarely ideological; they’re negotiated through patronage networks and party allegiances. Still, their shared working-class origins lend them moral weight. Many of these actors come from modest economic or caste backgrounds—Khesari Lal Yadav famously sold litti-chokha before he sang his way to fame. Their entry into politics represents a second social ascent. The promise of representation of “one of us” entering the corridors of power adds a moral texture to their popularity.

If Tamil Nadu made gods out of MGR, Rajnikanth and Jayalalithaa, Bihar props folk heroes who are more relatable than divine. The Tamil star-politician governed through myth; the Bhojpuri one operates through mimicry. He reflects his audience’s struggles rather than giving them a pedestalised figure to worship. Moreover, Bhojpuri stars command an emotional geography that other politicians envy. In a state where migration is the dominant life experience, supporting one’s favorite actor-turned-candidate becomes an act of reclaiming dignity for a community long caricatured by mainland media. In this sense, their politics is also a politics of belonging.

Several of Bihar’s political figures outside cinema, such as Anand Mohan Singh or Pappu Yadav have cultivated an image of the “Robin Hood”, who protects his people from the system. If anything, Bihar’s fondness for Bhojpuri cinema is a study in masculine restraint and vulnerability. These stars sing of heartbreak one moment and flex biceps the next, promising both affection and aggression. Their appeal lies in this contradiction—the assurance that power can also weep. In a region historically caricatured as lawless or backward, such performative pride becomes its own kind of resistance.

Yet the halo of celebrity can fade quickly. Voters in the constituencies where these stars have stood for elections, have proven capable of separating cinematic loyalty from political performance. Nirahua’s 2019 defeat in Azamgarh, for instance, was a reminder that charisma doesn’t always convert to votes. Manoj Tiwari, though successful electorally, has faced criticism for prioritizing performance over policy. The phenomenon’s endurance depends on whether these stars can evolve from symbols of identity to agents of governance.

For now, though, their appeal remains potent. A lot of politics today is theatre, and Bihar simply admits it more honestly. The actor, the strongman, and the neta are three masks of the same performance. At its core, the rise of actor-politicians in Bihar reveals how deeply performative our political culture has become.

Acting, singing, and campaigning are no longer separate professions—they are overlapping performances within a shared economy of attention. In this theatre, gangsterhood, celebrity, and power are merely different costumes of the same archetype: the man who can command a crowd. For Bihar, the challenge lies not in the existence of this phenomenon but in what it says about representation itself.