Many of us in the Northwest feel a certain privileged connection with Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan because of his six-month residency at the University of Washington Ethnomusicology Program from September 1992 to March 1993. Students and staff from across campus registered for his classes, and others from off-campus and even out-of-state came to register for his classes through University Extension, just for the chance to sit with him in small groups to learn qawwali.

Those were heady days for many of us in Seattle, when Nusrat could be seen walking around the block in his Adidas athletic clothes, at a public swimming pool with some of his students, riding one of the Washington State ferries, or shopping at a local Pakistani-Indian grocery store where surprised customers recognized him, spoke to him, and sent him gifts of halaal lamb, rice, etc. His 5-bedroom home in Lake City was always full of friends, students, family, musicians, fans and promoters. Nusrat enjoyed his relative anonymity in Seattle which permitted him to do what he could never dream of doing in Pakistan.

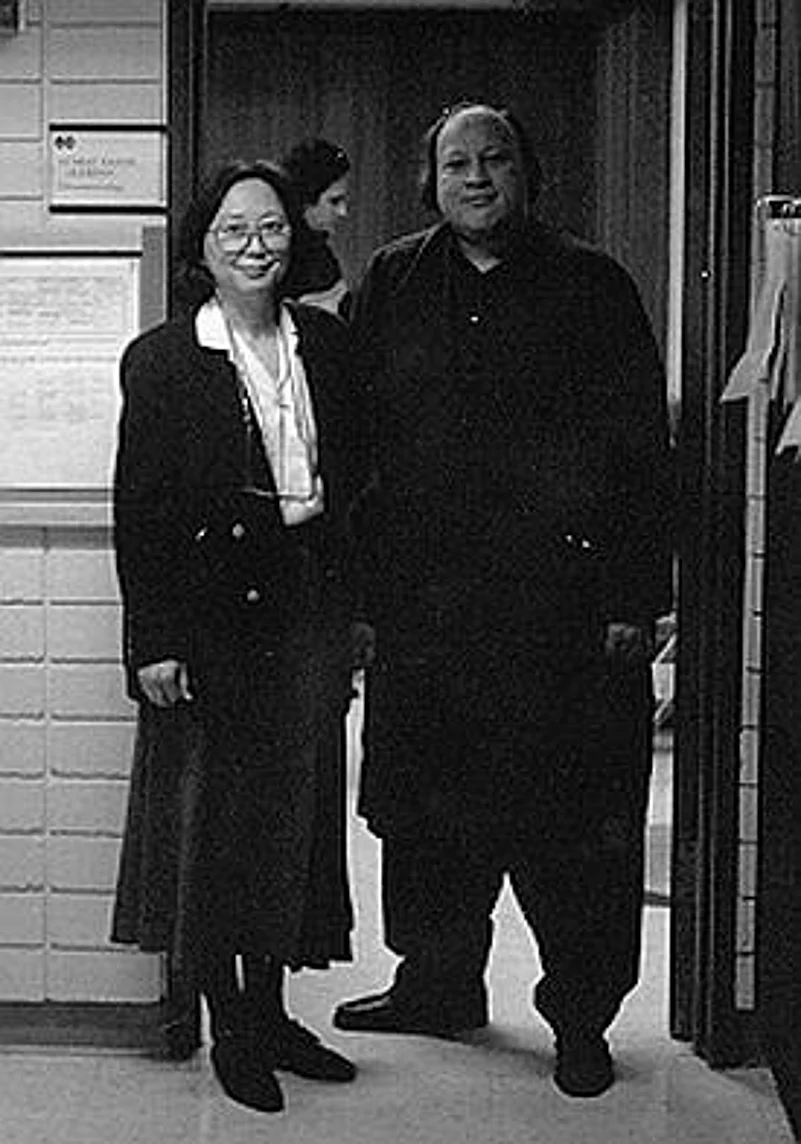

| Professor Hiromi Lorraine Sakata with Ustad Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. Photo: Shantha Benegal |

Nusrat’s decision to accept his teaching position at the University of Washington was not an easy one to make. On the negative side was the fact that the position was for Nusrat alone, not for his entire qawwali party. The livelihood of approximately 100 people (families of his ensemble) depended on the performances of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and his Party. How could he take six months out of his full performance schedule and still help the members of his ensemble maintain their livelihood? On the positive side was the full health care benefits provided to full-time faculty members. Even his ensemble members could see that Nusrat needed the time to seek special medical attention at a top-rated medical facility. Another perhaps more convincing reason was the opportunity for Nusrat to reach out to new audiences to convey the Sufi message of love, for he took his missionary work seriously. What could be more exciting for him than to spread the spiritual word of love to new, western university audiences? He was always a musical innovator who incorporated the sounds that attracted his listeners everywhere.

Understanding his dilemma, we worked out a schedule that would allow him to concertize on weekends. He would teach all day on Mondays, Tuesdays and Wednesdays, and half-a-day on Thursdays. Thus he was free to travel for weekend concerts. Members of his troupe would come to Seattle and stay with him for weeks at a time in order to perform with him. His wife and daughters also came to stay with him for a few weeks. Although this schedule seemed reasonable, it soon became apparent that it was a gruelling schedule that conflicted with the advice of his doctors who were mainly concerned about his high blood pressure and diabetic condition. His doctors wanted him to watch his diet and reduce the stress of his travel schedule. At one point, a sincere, but frustrated doctor asked Nusrat the rhetorical question, “do you want to die?” He gave the answer of any good Muslim, “if God wills.” For Nusrat, there was never a choice between his music or his health, or anything else—Nusrat lived for music and it trumped everything else in his life.

The highlight of Nusrat’s residency at the University of Washington was his faculty concert at Meany Theater on the evening of January 23, 1993. Since Nusrat was teaching qawwali, I wanted the faculty concert to be a traditional qawwali concert involving his entire ensemble of 10 musicians. Nusrat agreed to bring his musicians for the concert at his own expense, however, when it became apparent that there was a possibility that his musicians would not be able to get their US visas in time for the concert, he invited Pakistan’s great tabla player, Ustad Tari Khan, (Abdul Sattar Tari) who was living in New Jersey at the time, to perform with him. Although Nusrat had arranged for all contingencies, I was beside myself with worry when I did not hear from the musicians until the night before the concert date—they had flown into La Guardia from Lahore and still had to arrange to fly to Seattle the next day! They finally arrived some time after noon, just in time for the sound check. They must have been exhausted and I could not imagine how they could perform that evening. In my more calm states-of-mind, I surmised that this must be the kind of hectic schedule these musicians were used to. I recalled how Nusrat and his ensemble always seemed to arrive a few minutes before (or sometimes, after) their scheduled appearance, coming straight from the airport to the shrine or concert hall, and performing with exuberance and energy that only they could muster, but these thoughts never entered my mind on the day of Nusrat’s Meany Theater concert—I was destined to be a nervous wreck!

Fretting back stage, I missed the rush of the audience who clamoured and climbed over seats to get to the best possible seats in the festival seating arrangement. Luckily, there was only one report of a sprained ankle in this mad dash. The concert was completely sold out with many friends of Nusrat managing to come backstage to plead vainly for extra tickets (which he didn’t have). The first part of the program was the singing of the classical rag “Gawati” with Nusrat’s brother, Farukh, singing and accompanying him on the harmonium and Ustad Tari Khan on the tabla. [1] This was a rare performance where I heard for the first time, Nusrat’s complete mastery of tala which he learned in his youth. Nusrat first learned to play tabla on his own when he was discouraged from carrying on his father’s and grandfather’s musical tradition. His parents wanted him to become a doctor. When his father realized that music meant so much to his son, he relented and started teaching his son tabla in earnest until his mother pleaded with her husband to teach him to sing instead because the tabla player always sat in the second row, often unnoticed by the audience. If her son was going to be a musician, she wanted him to sit and be seen in the front row.

I managed to peek out from backstage after the beginning of the qawwali program to view the fully engaged audience and came out to stand near the stage on the side of an aisle. Audience members started to come up to the stage to make offerings (vel) to the musicians, some by discretely placing money on the stage, others by flinging or scattering bills over the heads of the musicians, and audience members began dancing in the aisles. Some people spied me standing by the stage and came to me to change their large bills into dollar bills. I was completely unprepared for this request, even as I suddenly recalled it was the duty of the manager of the group to make change available for the listeners. I soon got caught up in the spirit of the evening, stopped worrying and joined the audience in experiencing one of the most invigorating and magical evenings in my life. [2]

Days after the performance, the excitement and stir caused by the concert abounded with exaggerated stories of thousands of dollars showered on the musicians and women throwing their jewellery to the musicians, neither of which were true to my knowledge. Some people complained that the concert was too brief, and in that, they were correct, for traditional Sufi performances go on until the wee hours of the night or the next morning, but in these cases, there are more than one qawwali group involved. Aside from the complaints of a too brief performance, of no arrangements to make change for vel, and of not enough available tickets, the glow from the memory of that evening remains and has become a part of Seattle lore (or at least a part of University of Washington lore).

1. Live in Concert, Washington University USA, Ustad Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. Released and Distributed by Oriental Star Agencies Ltd., CD SR 108. It never occurred to the CD producers, or for that matter, the musicians, that there is a distinction between the University of Washington and Washington University.

2. The qawwali portion of the program sans the encore, can be seen on Nusrat! Live at Meany. Arab Film Distribution, 1998. www.arabfilm.com.

Professor Hiromi Lorraine Sakata is Emeritus Professor at the Department of Ethnomusicology at UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music and originally wrote this remembrance for the internet journal Ragavani in 2007 and graciously allowed us to publish it here.

***

Also See: NFAK Playlists