Maqsood Karim of Turkman Gate, old Delhi, is a strapping, tall man who, as batsman, would proclaim the sixers he was going to smite; he’d then match words with deeds. But he has remembrances far more sombre than the matches he played in his youth. In his mind are etched dates that shaped the Muslim psyche over the last 34 years—the removal of shops of the poor in old Delhi in 1975; the demolition of flats at Turkman Gate in 1976—“with 52 bulldozers in one night”; the violence at Meerut during Ramzan in 1981, and the 1983 Nellie massacre; the assassination of Indira Gandhi in 1984 and the resultant change in leadership, “causing the opening of the gates of the Babri Masjid in 1986”. The narrative of the 1980s, from the Muslim perspective, was marked by strife and uncertainty, and beginning to be soaked with a feeling of self-pity and victimisation.

And then, Karim fondly remembers, there was Mohammed Azharuddin.

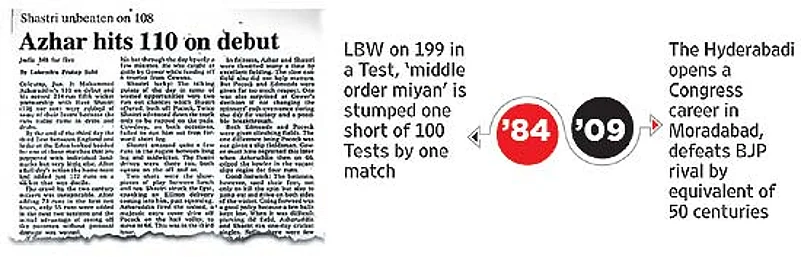

On the last day of Year 1984, a lanky young man from Hyderabad first played cricket for India, in Calcutta against the touring Englishmen. At stumps on the first day, Azharuddin was on 13 runs; rain and smog allowed him to add only eight runs in 20 minutes on new year’s day; January 2 was rest day. On the third day, Azhar made his first Test century—the ninth player do so on debut for India. And then, the next two Tests saw him score two more centuries, an unprecedented feat.

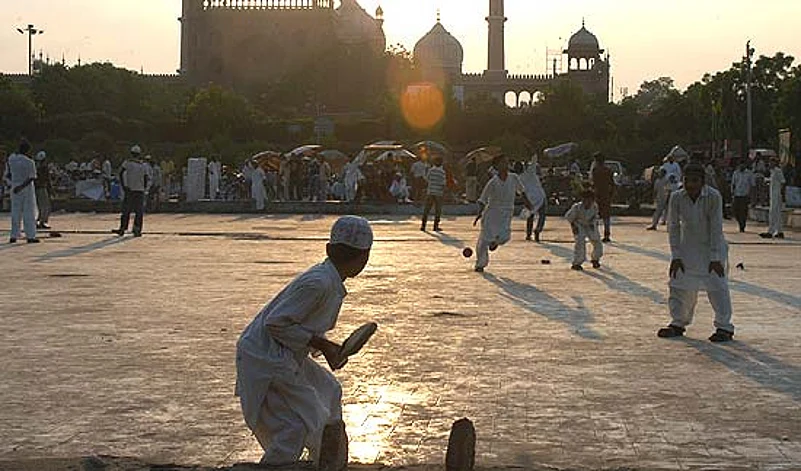

Azhar’s emergence, especially his performance against the touring Pakistanis in 1987 (when he scored two Test centuries), inspired Karim to play cricket. This seems to have been the trend in many localities. For instance, Abdul Sattar and Kamal Nigam, who live in the Muslim-dominated old Delhi and also run cricket clubs, say Azharuddin, playing with rare grace, aplomb and a lithe athleticism, drew Muslims to the game. “His approach was positive, his fielding electric,” Nigam remembers. “Football was more popular in old Delhi earlier. But after Azhar, young people started following cricket more.”

The impact beyond the boundary was much more marked in his hometown, Hyderabad. With Azhar’s continual rise, culminating in him becoming captain, change set in. “The community had been in a sort of depression,” says Amir Ali, editor of Urdu newspaper Siasat in Hyderabad. “Having ruled India for 400 years, they’d talk about the contribution of ancestors in the past. But confronted with reality, they had preconceived notions of prejudice. They thought: ‘We can’t get jobs. We’re being discriminated against.’”

That has changed over time, says Ali. And Azhar has much to do with it. His supple wrists and those drives of limpid, fluid grace elicited universal praise and the sheer sense of elan he generated—it seemed to spread out from him. The community’s identification with Azhar was not communal as the term is understood; it didn’t, for instance, mean demanding privileges at the expense of others. It was in fact the reverse: Azhar came as an exemplar, a symbol of hope for Muslims, drawing them into the mainstream, making them believe that talent is recognised and awarded in secular India. Not just in cricket, but in other fields, in jobs, in life.

Azhar had a greater, more profound effect on that vexed problem of Pakistan. Muslims are periodically accused of sympathising with Pakistan, of supporting their cricket team even against India—and it has all the force of a self-fulfilling prophecy. It’s a classic case of psychological switch—not being accepted, perpetually suspected, an outsider often becomes or pretends to be what he’s accused to be.

Businessman Haseeb Ahmed, 29, cites an example. The night India beat Pakistan to win the Twenty20 World Cup in 2007, Ahmed and his friends went to the India Gate, seeking, like hundreds of others, fresh air and ice-cream. Since it was the month of Ramzan, he and his friends wore sherwanis and skullcaps, looking every inch the stereotype Muslim. “Here we were, delighted at India’s win, and then a group of young people, including women, started abusing us,” recalls Ahmed with disgust. “They were saying ‘we’ve beaten you’. This sort of thing happens often—it’s frustrating.”

But many Muslims are dismissive of such incidents, their nationalistic resolve in cricket hardened over the years, courtesy Azhar’s rise to the pinnacle of glory. After him, there was a deluge—Zaheer Khan, Mohammed Kaif, the Pathan brothers, Munaf Patel. Indeed, the Azhar phenomenon helped instil confidence among Muslims, enabling them to brush aside taunts from Hindu chauvinists. It worked equally on non-Muslims—Azhar’s performance undercut the appeal of, say, Bal Thackeray to Hindus susceptible to the Muslims-support-Pakistan rhetoric.

The Siasat editor says earlier, in sensitive parts of Hyderabad with mixed populations, people would burst crackers, with no intention other than to pique the other community, when India or Pakistan won a match. Sometimes, this caused clashes. “Now that’s changed completely,” Ali says. “Muslims realise bitterly how they’re suffering due to Pakistan’s mischief-making in India, but Azhar has been a factor, too, an important one, especially after he became captain.”

After Independence, prior to Azhar, India had one Muslim captain—the charismatic Mansur Ali Khan Pataudi. Abbas Ali Baig too was a popular star. But they were aristocrats, not easy for the Muslim masses to relate to. There was also the vastly talented but mercurial Salim Durrani, but he lacked consistency, was in and out of the team. Unlike him, Azhar was one of the greats, a middle order titan, India depended on his performance. Above all, Azhar’s was a rags-to-riches fairytale. A story the lower-class Muslim could relate to, pine for, aspire to. His rise also coincided with the cricket and TV boom in the ’80s, making him a bigger icon than his predecessors.

Boys like these, playing cricket near Delhi’s Jama Masjid, have come in Azhar’s wake

But Azhar became a Muslim icon also because he was one bright spot in those gloomy decades. “To the Muslim eye, he was an assurance that even in a situation where most people carry a communal outlook, one could make it to the very top. Azhar disproved the belief of bias against Muslims,” says political scientist Imtiaz Ahmed. “He also demonstrated that with effort and energy, you can make it, even if the odds are against you. Azhar became an idol of the Muslims.”

Pataudi too had been that. In fact, Shahid Siddiqui, editor of Urdu weekly Nai Duniya, believes Pataudi presided over the Indian team in much more fluid and uncertain times. “When Pataudi batted, Muslims would pray, with tears in their eyes, I remember,” says Siddiqui. “In fact, the 1971 war with Pakistan was the watershed for Indian Muslims. The illusion of Pakistan as protector of Muslims was shattered.” Bangladesh was born, discrediting the two-nation theory.

Among Muslims, those not wedded to the idea of India were deprived of an alternative, competing nationality. Siddiqui says such Muslims used to migrate to Pakistan even in the 1960s—the cricketer Asif Iqbal, for instance, did so in 1961. Post-1971, Indian Muslims had no choice but to fight for a place in India. “Azhar was the face of the confident Indian Muslim,” says Siddiqui.

But for Azhar, unlike Pataudi, there was also a fall from grace. And it was not merely because he was accused of match-fixing. Most people Outlook spoke with—man on the street, cricketer or expert—emphasised that his divorce was more damaging than the match-fixing allegations. Take Delhi sales executive Uvais Karim, 29, who says he has no doubt that Azharuddin’s biggest mistake was to divorce his first wife. Karim wonders if there was any truth in the match-fixing allegation. Former Uttar Pradesh bowler Obaid Kamal agrees, “The veracity of those allegations can be doubted. But the divorce is a fact. Everyone asks me why he did it. I’ve had to explain to thousands of people that he had reasons.”

Imtiaz Ahmed too says Azharuddin’s divorce ended the period of obsession, he was idolised no more. Before that he was extraordinary; now he was shown to be quite fallible like anyone else. “Personally, I believe he tried to settle it as amicably as he could,” Ahmed adds. “But the divorce and his second marriage have stuck in the Muslim mind.”

Happily for him, so has all the good work he did on the cricket field. Nine years after he last played for India, Azhar still causes a minor melee when he steps out on a street in Hyderabad; it’s why he could win an election from Moradabad, UP. Azhar is the reason why the likes of Karim or Sattar—perhaps lakhs like them—picked up bat and ball and dreamt of playing for India.