It's a late night ride back to McLeodganj, after dinner at the home of filmmakers and directors of the Dharamshala International Film Festival, Ritu Sarin and Tenzing Sonam. We are telling each other our Himachal Pradesh stories. Mine is the one to do with the secluded Malana village, how its quaint inhabitants regard themselves as descendants of the Greeks and treat all outsiders as untouchables. It had created much mirth and amusement in my family that I too had been treated like one when I had gone there on work.

For soft-spoken poet and filmmaker Nagraj Manjule, travelling quietly with us that night, untouchability, however, has not been something to laugh about but an ugly reality he has had to contend with almost every single day of his life. No wonder next morning his stark and hard-hitting depiction of it, in the Marathi film Fandry, brings my latent guilt to surface. Yes I may not have been prejudiced but did I ever truly empathise and engage? I may have been sensitive as an individual but did that remotely alter things in the larger social canvas?

Fandry is about a much oppressed family of pig catchers living on the very margins of rural Maharashtra. They trap pigs for their daily meal, the very pigs who feed on human excreta. The film implicates many a privileged viewer in the humiliation of its young Dalit protagonist Jabya, specially in the long, harrowing last sequence capped by a jolting climax. It reproaches and in turn brings out our collective remorse.

We discuss this over lunch. I tell Nagraj how throughout the film I felt one with Jabya and his forbidden love for the high caste classmate Shalu till the last scene made me realise my own otherness in his world. We talk about how not asking anyone their surname, dismissing caste talk with the shrug of a smug shoulder is also a privilege of those who are already entitled. "Most have no choice. Caste biases are too finely entrenched to vanish with the personal correctness of a few. The stigma of caste remains," says Nagraj. No wonder some viewers, despite having witnessed a devastatingly unequal and inhuman world in the film, still ask Nagraj about the "lopsidedness" of caste-based reservations. His argument is clear-eyed: "Reservations are necessary till everyone reaches the same stage, when everyone can run the race from the same starting point. But Dalits are still more than 500 metres behind the rest."

That inequity also holds true in the world of mainstream cinema, that knows only two Gods--money and success. "We embrace Dalit characters like Kachra in Lagaan only when we need him to win the battle against the Britishers," says Nagraj sarcastically. He himself was asked to change his name to M. Nagraj to hide his caste. A Dalit crew member told him how he felt one with the film, but he said so in private. Nonetheless Nagraj is hopeful that this veil of secrecy may lift one day. "At one time Dilip Kumar, Meena Kumari adopted Hindu names to mask their Muslim identity. Now the filmdom is openly dominated by the Khans. Tomorrow Dalits may also come to rule Bollywood," he says, quickly adding: "Hiding your identity is not a good thing, openly talking about your caste is not a big deal either. One should only be proud of being a good human."

It's a focus on such significant social issues that seems to have become DIFF's calling card in just two years of its existence. The spirit goes well with the region's consistent politics and its long-standing support for and seminal engagement with the Tibetan cause. Most of the chosen films are driven not just by the aesthetics and craft but a distinct independent spirit.

Like Amit Virmani's Menstrual Man, about Muruganatham's fascinating journey in producing affordable sanitary napkins for the poor women who otherwise end up using unhygienic rags and husk during their periods. A school dropout and a man of limited means Muruganantham shows the way to a successful social entrepreneurship model, that he himself calls the Butterfly model as opposed to the Parasite model of profiteering. It hasn't just made basic hygiene accessible to the poor but the various, easily assembled machines and production units have also given them sustainable means of employment. The quirky film comes alive with Muruganatham's own self deprecatory humour and the many jokes about his weird research methodology--involving artificial uterus, football for a bladder, goat blood and even wearing the pad himself. It made his wife and mother think of him as some pervert. Amit highlights these dramatic moments by using melodramatic clips from Bollywood films. But between the many laughs Menstrual Man's essential cause is never forgotten: not to scale up but scale deep to reach the sanitary drive to the remotest corners of India.

Nishtha Jain's Gulabi Gang is also driven by the rough sense of humour of its central character, Sampat Pal. She is the leader of the pink sari-clad gang that fights for justice for women and Dalits in Bundelkhand. Their battles could be as diverse as irregularities in the BPL schemes or the mysterious death of a young woman. Most of these vigilantes are uneducated, their feminism unstudied, the subversion of patriarchy is spontaneous and the need for change is strong. Yet the movement itself is weighed down by its own complexities, dichotomies and dilemmas. They come to fore when one of the activists sides with her family than the movement on the issue of honour killing. But Nishtha doesn't take sides, she just presents the situation without pronouncing any judgement. As she herself says: "It's good to maintain a distance. There is a danger in romanticising such a movement. I have tried to present a realistic picture than turn it into some kind of a hagiography." And that's what makes the film powerful.

***

A few weeks after Dharamshala I bump into Nagraj Manjule again. This time at the International Children's Film Festival India (ICFFI) in Hyderabad. He is talking to the press about how our mainline feature films are becoming "bachkaani" (childish) while our children's films talk more serious and sensible stuff. Not just his debut feature but the award-winning short, Pistulya, has also been about kids, more specifically their struggle for education. I wonder if the kids would understand the caste debate of Fandry. He informs me that they do, specially those from the Andhra Pradesh schools.

The child viewer is not juvenile, I realise. Renowned filmmaker Raj Kumar Hirani, while watching films along with children, admits they can actually be very demanding. "There's an immediacy of response. They either get deeply involved or may get easily distracted," he says, adding that "the information overload and attention span deficit of today's generation makes things more difficult." He finds it daunting to even think of making a film for them or work with child actors. But a project has been playing at the back of his mind which he might get involved with once Peekay with Aamir Khan finds a release in June 2014.

What's more the children are also taking on the likes of Hirani by turning filmmakers themselves. Be it a ghost story or that on bullying or a homage to the school sweeper, they seem fairly evolved in their narratives as witnessed in the section on films for kids made by the kids themselves. "All we need is a story and a camera, even the one in a mobile will do," says one precocious child filmmaker.

No wonder Children's Film Society of India, the autonomous body in charge of production, distribution and exhibition of children's films under ministry of I&B, has also had to grow to keep up with its changing audience. "The Little Directors section barely had any entries in the last edition. This time we received more than 123 films," says CFSI CEO and festival director Shravan Kumar. According to him the budgets of children's films have increased, so has the stringency in quality control and transparency in green lighting the projects. "We are willing to give from Rs 2 crore to as much as a project demands," he says. There's acclaimed director Buddhadeb Dasgupta's Woh, based on Rabindranath Tagore's Shey, on his own relationship with his granddaughter. Six other films are on the floor. The marketing and distribution bottlenecks are also being addressed. "We tied up successfully with schools for block bookings of Gattu. We are also trying to include some of our films in the school curriculum and keep trying to take them to screens in tier 2 and 3 towns," says Kumar.

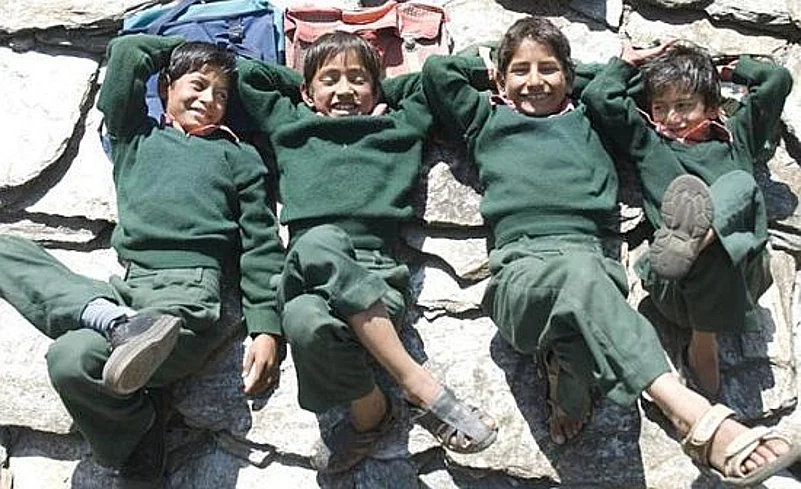

One small, simple yet nuanced take on the complexities of childhood screened at the festival is Batul Mukhtiar's Kaaphal (Wild Berries). Batul confesses that she finds it easy to talk and listen to the kids, write stories for them and working with them. Set in a remote village in Uttarakhand her film uses local kids as actors, one of the reasons why it feels rooted and authentic. Let alone working in stage or films these kids hadn't even seen a film in a theatre. Kaaphal's screening in Ranga theatre turned out to be their first.

Kaaphal is set in a village that has no men. They have all left the hills in search of jobs. There are only women, their kids and a few old men around. And many tales about the "pagli dadi" who lives on the outskirts. It's a carefree, fun life that gets broken one fine day when the father returns and decides to instil some discipline. Soon the excitement of meeting him gives way to an intense desire to see him leave home again for work. He becomes a nuisance as he curbs their freedom and mischief. The film talks about one of the most central feelings of any child: unquestioning love for a parent that gets broken at times by a strong hatred. A film that an adult can identify with as much as a child.