On September 9, at the break of dawn, Yameen and his family fled Kutbi, their ancestral village, in a military rescue truck after a night of terror where they were besieged by hundreds of armed men. “Some 300 people, the Jats of Kutba and Kutbi along with outsiders, pounced on us with guns, knives and lathis. We hid for 12 hours, fearing for our lives every second,” says Yameen.

In Kutba, it started the day before. Tractor-loads of Jats were returning from a mahapanchayat held to mourn —and debate—the death of two boys of the community in Kawal. The entourage was attacked, four people died. After the resultant bloodbath, people like Yameen joined thousands who fled their villages across this belt of western UP, to become refugees in Muslim-dominated hamlets. Nine weeks later, the social landscape of Muzaffarnagar continues to alter.

A steady stream of ‘tempos’ litters the highways, packed with Muslim families and their possessions as they leave their mixed-community villages. “We will never return,” says Yameen. “We sharpened the Jats’ farming instruments, their ploughs and sickles for generations...and they used the same things to cut us. We’ll never return.”

In Kakda, a few miles away, some Muslim families have returned from the camps to gather their belongings. They are not staying, which seems enough reason for the Jats and other Hindu residents to taunt them. “We never asked you to leave, but if you’re going, don’t come back,” a group of women hiss at Ibrahim and Ilyas, as they load a tempo with their cot and few other meagre possessions. The story’s the same throughout this belt, Shamli, Sisauli, Shahpur, Jauli, Bahavadi, Phuguna, Bohpa—it’s evident that a new phase of reorganisation, or call it ghettoisation, is well under way in western Uttar Pradesh.

There are some 1,000 refugees in Shahpur’s Camp No. 1, and it is lacking in everything essential. “From food to water, toilets to healthcare, the state only provided help for 15 days...we’re on our own now,” says Irfan, who moved here from Kawal, the epicentre of the riots that broke out in late August. And where the state moves out, other players move in. In Shahpur, even the tents providing shelter are provided by the Jamaat. The children say they want to return to school but it’s difficult, most of their documents were lost in the melee. Some parents, reluctantly, are letting the children join madrasas instead of regular schools. “We are living off charity, dying slowly without any work,” says Ibrahim, a mason who also came from Kawal two months ago. “We don’t have the luxury of choice.”

The women are worse off. Underage or not, over 200 have so far been married off in haste as their families pass on the job of protecting them to their husbands. Many women have been transferred from one camp to another. Almost every tent has a family member who died—some in the violence, some at the camps after catching some disease.

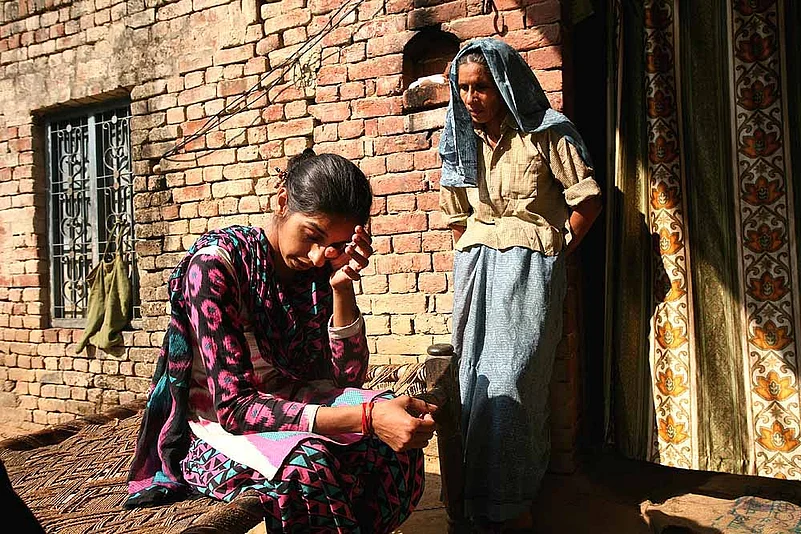

Muslims from Kutba village at a relief camp in Shahpur, Nov 5. Not one Muslim family remains in the village. (Photograph by Sanjay Rawat)

Back in Kutba and Kutbi, the Jats claim they made “repeated requests” to the Muslims to return. “Some of them did return, but then the government announced Rs 5 lakh compensation for people who lost their homes. So they left once again,” says a relative of the local pradhan, Devinder Singh. He says the Jats will vote for the BJP in the coming elections (“this government has displayed a biased attitude”). Dr Jitender Singh, head of a prominent land-owning family of Kutbi, though, is more worried about the harvest. “The cost of getting work done has jumped dramatically after the Muslims left. The sugarcane is rotting in the fields with no one to harvest it.”

In the Jat hamlet of Malikpura, Ritu Kumari, 21, carefully thumbs through a magazine, a picture of anger and distress. “If only the government had been ours,” she says. “Nothing would have gone wrong if the government had not been partisan,” her father Bishan Singh interjects. A headline in the magazine, the Rashtriya Jat Kranti Patrika (National Jat Revolution Magazine), screams: ‘Behen ke maan-samman ki raksha ke liye mamere bhaiyon ka balidaan (Cousin brothers sacrifice their lives for the honour and dignity of their sister)’. The magazine is published by Ashok Katran, a former journalist from Jansat near Muzaffarnagar. He says people are “very sensitive” about women being harassed. “It’s a serious issue here,” he says.

Ritu was just another college girl, passing through Kawal daily. She never told anyone about Shahnawaz who used to allegedly “abuse her”. “I was afraid my brothers would get angry if they found out. That day my brother Sachin was escorting me home. When Shahnawaz accosted me, he saw it,” she says. Sachin and his 17-year-old cousin Gourav later confronted Shahnawaz. “They sent me home alone. I don’t know what happened next,” Ritu says.

What happened next is unclear, but Ritu’s brothers didn’t make it home alive. Neither did Shahnawaz. The deaths triggered a storm of violence that’s left over 70 dead, most of them Muslim, hundreds more injured, and thousands of Muslims homeless. The region is simmering with discontent like never before. The relentless Jat refrain is of “ek-tarfa karrwahi” or one-sided action against them by the state government. How true this is is anyone’s guess: the makeshift camps in which 20,000 Muslims (down now from a peak of 50,000) now live a destitute existence tell another story.

That the Samajwadi Party government misread the situation and more, played votebank politics, is by now a given. The Jats are furious for initially no compensation was announced for them. The state did so later, but only after protests. It took more protests to ensure that dead Jat and Muslim victims got the same compensation—Rs 10 lakh. “They want to benefit from compensation...they set fire to their own homes...they don’t want to repay our loans,” allege Jat landlords in Kutba and Kakda’s Hindu residents. The administration also stands accused of filing FIRs quite at random. “There’s no thought going into who they are filing cases against,” says RLD’s Chauhan. The SP, meanwhile, has sought to paper over the crisis: “The Muslims have returned to their villages. There are very few left in the camps,” says SP district president Pramod Tyagi. He adds that the moment relief measure are announced for one group, the other pipes up alleging favouritism. This is true too: both Jats and Muslims, left to the mercy of religious bodies, have dug in their heels.

Muslim families in Kakraula village loading up their belongings to leave for the relief camp, Nov 5. (Photograph by Sanjay Rawat)

“They registered FIRs against us and our family,” say Sachin and Gourav’s fathers, Bishan and Ravinder. Both claim they weren’t present at the site of the crime. And they chafe over the fact that they are being prevented from joining the string of Jat khap meetings (now rechristened “shok sabhas”) where politicians of every hue—BSP, BJP, SP, Congress—have been straining at the bit.

Some 437 riot-related FIRs have been filed in two months, says Chandervir Singh, a prominent lawyer in Muzaffarnagar. Chandervir, who is vying for a BJP ticket in 2014, is representing all the Jats (and other Hindus) accused in the FIRs. So far, 5,000 people have been named in FIRs and 14,000 “unknown persons” have been charged—an “indication of outsiders” playing a much greater role in the violence than is being acknowledged. Harinder Singh Malik, a prominent Jat leader and ex-Congress MP, says the Jats are afraid of admitting that “outsiders came to Muzaffarnagar to cause riots”.

Leaders also say the violence this time is being engineered along fresh lines of discontent, the “bahu beti izzat” issue in particular, to whip up emotions. “If there were no elections in 2014, there wouldn’t have been any riots,” Chauhan says.

Rakesh Tikait, Bahujan Kisan Dal (BKD) leader and the late Mahendra Singh Tikait’s son, says he spent Diwali in Bijnor with thousands of cane farmers protesting against payments of roughly Rs 280 crore being delayed by a year by the sugar mills. With the Muslims having fled and others reluctant to leave their homes in fear, this year’s crop of sugarcane lies uncut, rotting in the fields. Tikait underplays the Jat element and says the riots were not Jat-Muslim but Hindu-Muslim. “Jats won’t get swayed as easily in the polls as people think today,” he foretells.

That’s not to say the political parties aren’t trying their best. The blood hasn’t dried but already parties are parrying for position, the latest being the move to add the Jats to the OBC central reservations list, a sure Congress-RLD move with 2014 in mind. After the communal uproar, will it now be a Mandal battlefield next?

(Some names have been changed)

By Pragya Singh in Muzaffarnagar