| “You question the legitimacy of state power. But you won’t condemn deliberate, heartless violence.” P. Chidambaram, Union home minister |

| “If media reports are true, (the attack) is absolutely inexcusable and cannot be justified on any count.” Arundhati Roy, Writer-activist |

| “Silence cannot be construed as complicity or approval. We have expressed disapproval at several forums.” Dr Binayak Sen, Activist | ||||

| “The Maoist issue can be solved through talks. The BJP is forcing the government to take harsh steps on them.” Narendra Modi, Gujarat chief minister |

| “Both Chidambaram and Raman Singh seem to be disciples of Bush. If you are not with us, you are against us.” Ramachandra Guha Historian |

| “You cannot say that you want to build a just society by means that are not human.” Harsh Mander, National Advisory Council | ||||

| “Dissenting voices help democratic functioning. It’s only when some civil groups maintain silence, it’s a problem.” Prakash Singh Former DG BSF |

| “The connivance of some rights groups with Maoists is what is dangerous. Some are financed by them.” Ajit Doval, Former director, IB |

| “Corruption built into a system which fails to deliver is more destructive than rights activists’ criticism.” K.P.S. Gill, Former Punjab DGP | ||||

| “Chidambaram should read Roy rather than get inputs from intelligence agencies. He should talk to civil rights groups.” K.S. Subramanian, Retired DGP |

| “Though I am critical of human rights groups, let us not confuse who our enemies are. The Maoists are the enemy.” Ajai Sahni, Inst. of Conflict Management |

| “When the Maoists say, ‘overthrow the state’, it’s like saying we don’t need the UN. Where do you go in a crisis?” Maroof Raza, Security analyst |

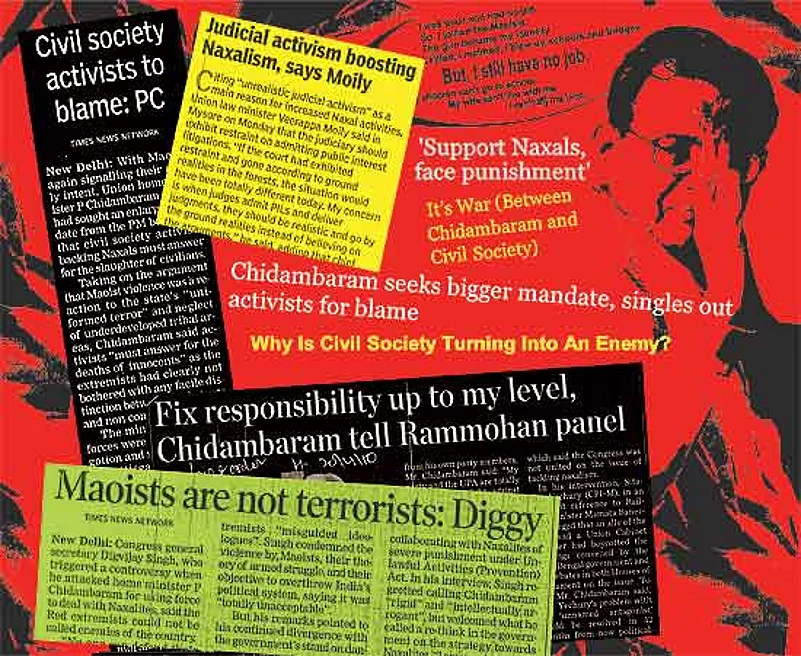

Welcome to the zero tolerance zone of dissent. Mostly located in the cool environs of a television studio, here power flows from the lung. And ever since the Maoists massacred 76 CRPF jawans in the jungles of Dantewada on April 6, that high-pitched power has been directed towards a new internal security threat: the Maoist sympathiser aka the human rights activist, and civil society.

Collateral damage Injured of the May 17 bus blast recover

They emerged Public Enemy No. 1 yet again when the Maoists struck a second time on May 17, this time blowing up a bus in which 16 civilians and 15 SPOs were killed. The deed done, the faceless, nameless Maoists retreated into the jungles, leaving the media to latch on to the more visible enemy: ones the media might describe in flattering terms as “well-read, articulate intellectuals” but who through Union home minister P. Chidambaram’s bifocals appear as suspicious sympathisers who must periodically be asked to prove their allegiance to the state. Their faces are flashed across TV screens, their names are vilified at will, they have become the favourite whipping boys in the state’s battle with the Maoists.

At the top of this hate list is writer Arundhati Roy. Asked about her in particular, Chidambaram told a TV channel, “She is such an eloquent writer. I wish I could write like her.” He was no less eloquent himself when he said it is civil society, to a large extent, that has weakened the efforts of the state governments in battling Maoists by questioning the government instead of questioning the Maoists. He was swiftly turning the battle between the Maoists and the state into an ‘Us vs Them’ debate by asking, and in some cases urging, people to stand up for the state.

Arundhati Roy did condemn the May 17 attack. To quote from her statement: “Media reports say that the Maoists have deliberately targeted and killed civilians in Dantewada. If this is true, it is absolutely inexcusable and cannot be justified on any count. However, sections of the mainstream media have often been biased and incorrect in their reportage. Some accounts suggest that apart from SPOs (special police officers) and police, the other passengers in the bus were mainly those who had applied to be recruited as SPOs. We will have to wait for more information. If there were indeed civilians in the bus, it is irresponsible of the government to expose them to harm in a war zone by allowing police and SPOs to use public transport.”

It was clearly not enough for the home minister. Endorsing the home secretary’s demand that “Maoist sympathisers” condemn the May 17 attacks, he said that “if the civil society organisations which rush to condemn the government question the legitimacy of government action and won’t say a word on what happened (in Dantewada)—that’s a very sad commentary on the state of our civil society organisations.” The home minister in fact went so far as to say that the chief ministers of state governments like Chhattisgarh had come to him and complained that they were spending more time fighting legal battles with human rights groups accusing the state of sundry violations and transgressions than tackling the Maoists.

This is a tricky situation for those who question the methods of the state in Naxal areas. “It’s a tightrope walk for the human rights groups, which have to demonstrate their neutrality,” says doctor and activist Binayak Sen, who was arrested for his alleged Maoist links and released after nearly two years in jail in Chhattisgarh. “But their silence cannot be construed as either complicity or approval. We have expressed our disapproval in many forums, irrespective of who engages in violence. In this case, a civilian transport cannot be made a target even if SPOs were travelling in it. We cannot approve of this collateral-damage principle.”

Walking against the comrades An anti-Naxal march in Jagdalpur

Noted human rights activist K.G. Kannabiran was equally indignant at the home minister’s call to express their condemnation of the May 17 attack. “Is this some kind of a Brahminical ritual that we need to stand up every time when attacks are perpetrated by the state or the Naxals?” he asked. “Does the home minister listen to us when we speak up on violence?” According to him, the recent massacre of civilians has to be condemned, and was condemned. “But did the minister hear us? It would appear that he focuses his attention only when we critique the state for its violence and not when we condemn a Naxal attack.”

As far as civil society groups see it, human rights violations by definition relate to those perpetrated by the state. The Maoists are not exactly the state but private actors and the violence they commit is an act of crime. The attack on the CRPF jawans and the blowing up of a civilian bus were criminal acts which have been condemned. The People’s Union of Civil Liberties (PUCL), in fact, issued a press note, roundly condemning the bus blast. “The killing of innocent civilians,” it says, “is the most heinous crime against humanity and has no justification whatsoever. PUCL feels that no objective could be desirable that is sought to be achieved at the cost of human lives and security. As is evident from the past experience, dialogue remains the most potent and viable means of lasting peace.”

This was a point driven home by Kavita Srivastava, the PUCL national secretary, on national television when the anchor sought to explain to her Che Guevara’s theory on the use of violence. “So, we have expressed anguish and horror,” she said. “The whole situation has gone far beyond condemnation. What we’re witnessing is a brutalisation of society. Does the state have a plan in place to counter the Naxalites? Can we go beyond just condemnation and see how we can address the violence?”

It is precisely this—post-violence analysis and reports written by human rights activists—that gets the state all hot and bothered. Essentially, human rights groups step in as inquirers or investigators into human rights violations. “We also investigate,” says Kannabiran. “So why blame us? We collect facts as courts do not take note of pre-trial illegalities and the state too is a party to human rights convention, so why is the state suspicious of what we do?”

Historian Ramachandra Guha endorses this viewpoint. “Any independent reporting or inquiry becomes very difficult in states like Chhattisgarh, which has its own laws to prevent such exercises,” he says. While Guha admits that there could be some front organisations for Naxalites, there are newspapers which are propagandists of the home ministry. “I, for one, am not a Maoist sympathiser and am completely opposed to violence on both sides.” Guha says the stamping out of dissent is worrying and, in Chhattisgarh, it is impossible to report because of the stringent law of the state—the Chhattisgarh Public Safety Act—which makes independent inquiry difficult. Guha was dubbed a Naxalite by the state’s top cop when he went to Dantewada two years ago as part of a fact-finding panel.

Ask for a securityman’s viewpoint and Prakash Singh, former DG BSF, will tell you where their problems lie. What is worrying, he says, is that the intellectual class, which has not been to troubled areas, gets swayed by the opinion of writers like Arundhati Roy. “When magazines publish articles by activists, they expose themselves to the charge of being a mouthpiece of the Maoists,” says Singh. Such articles also encourage the Maoists, as publicity is oxygen for them.

Under fire Arundhati’s ‘Walking with the comrades’ is now being attacked

Ajit Doval, former director IB, is more charitable. One can’t paint all human rights groups with the same brush, he points out. “Some are definitely fronts of the Naxal groups while others are ideologically sympathetic,” says Doval. “The silence of civil society per se is not disconcerting. But if we have a law that prohibits abetting and supporting Naxals, then the law has to be followed.”

It is, however, when there is some real soul-searching that former cops start seeing eye to eye with civil society. So when former Punjab DGP K.P.S. Gill asks what use is a highway in Dantewada to a tribal when his basic needs of a hospital, school or employment are not addressed, one wonders whose side he is on. Or when he observes that “corruption built into the system which fails to deliver is more destructive than the criticism of the civil rights groups”. It is a view that is echoed by former IPS officer, K.S. Subramanian, when he says that there is a lot of structural violence in the state, and Naxal violence is a response to it. According to him, Chidambaram should perhaps start listening to human rights groups instead of relying heavily on intelligence inputs from cops who have a security mindset, oblivious to the larger issues of structural imbalances, development issues and displacement.

Perhaps that’s the advice the home minister should take. Listen to human rights activists for a change instead of blaming it all on them. And then listen some more.