It wasn't the most propitious start to the life of a man who, in the years to come, was to become a powerful Communist leader in the world's largest democracy. But in the autumn of 1948, when he was barely six months old, Prakash Karat fled his birthplace—Letpadan, 100 miles north of the Burmese capital, Rangoon—in a truck, to escape advancing Communist insurgents. It was the year Burma, now Myanmar, gained independence from the British on January 4, only to be engulfed in successive insurgencies by the Red Flag Communists and the White Flag Communists, led by army rebels calling themselves the Revolutionary Burma Army.

"That, ironically enough, was my first brush with Communism," recalls an amused Karat. "My mother, sister and I were evacuated from Burma, along with other Indians. We went to Palakkad, in Kerala, where I spent the next four and a half years, before returning to Rangoon to rejoin my father."

For Karat, the next four years in Rangoon, spent in a railway enclave—his father, Chundoli Padmanabhan Nair, was a clerk in the Burma Railways—are bathed in the golden glow of an idyllic childhood. Home was a wooden bungalow with polished teak floors. The neighbourhood was filled with children. Karat learned to speak Hindi at the Indian school he attended and Burmese from his friends. Those were magical years—watching football matches, for instance, at the nearby 40,000-seat Aung San Stadium with his father (football remains Karat's favourite sport, which he follows to this day). "I remember an Indian team once playing a Burmese team, but I was rooting for the Burmese. I had a certain feeling for Burma already," says Karat. Or playing with friends on the empty platforms of the newly-built Rangoon Central Station. "Very few trains passed through the station, thanks to the continuing insurgency," says Karat, "so we children had the free run of the place, which was walking distance from my home." And then there was the food: while the meals at home were traditional Malayali, there was wonderful Burmese street food in the bazaars waiting to be sampled. And finally, he recalls, the lazy Sunday picnics with other Indian and Burmese families at the lakes that dot Rangoon.

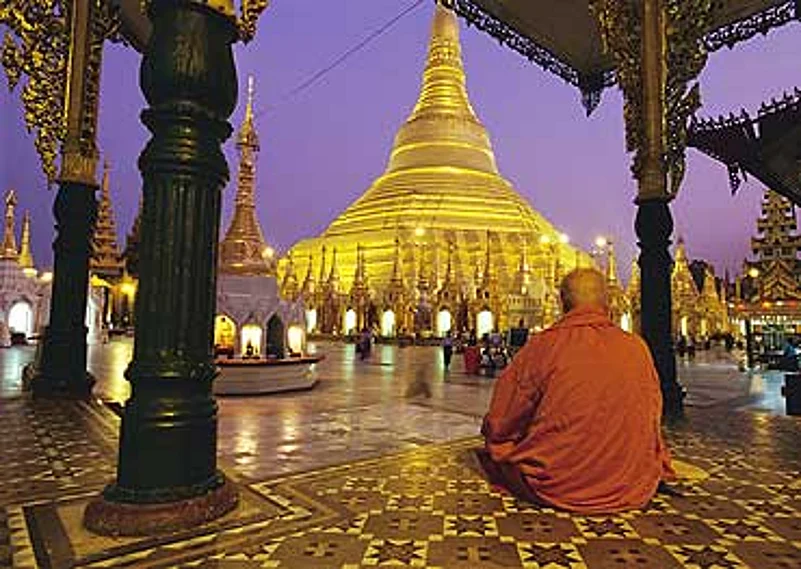

"One of my most abiding memories of that time is the Shwedagon pagoda, one of the most sacred Buddhist temples," says Karat. As he sits in his spartan office at the CPI(M) headquarters, it is evident that more than 50 years later he is still mesmerised by the memory of the radiance that emanated from the pagoda, its great golden stupa dominating the Rangoon skyline. But it was not just the dazzling beauty of the pagoda that drew Karat to it. "People would throng the place not just for worship; it was a meeting place—things happened there." Indeed they did: in 1920, students held a protest strike here against the new University Act which they believed would only benefit the elite and perpetuate colonial rule; and in 1938, oilfield workers established a strike camp here. In January 1946, Gen Aung San addressed a mass meeting at the pagoda, demanding "independence now" from the British. (Forty-two years later, in 1988, his daughter Aung San Suu Kyi too would address an enormous crowd here, demanding democracy from the military regime.)

Of course, Karat didn't witness any of these events—he had only heard about them. But one afternoon, just outside his home, he saw a large body of monks clash with the police, who charged them with their batons. "That afternoon still remains vivid in my memory. I stood there bemused, I had never seen anything like that before." In the years to come, once he joined politics as a student, clashes with the police would, of course, become commonplace.

So how did Karat's parents come to be in Burma, so far from their native Kerala? "It was an old British colony and many people from India, particularly Bengal and Kerala, went to Burma for white-collar jobs, like my father's elder brother had—he worked in the accountant-general's office there. So my father too moved there in the 1940s." In the case of his mother, Karat Radhabai, she had been adopted by her elder sister and brother-in-law, who was a doctor in Rangoon. "My mother grew up in Burma and when she met my father, she decided to marry him," Karat says.

Insight and change: Shwedagon temple hosts both meditators and protesters

That four-year idyll came to an abrupt end, when Karat's sister Kamala, four years his senior, tragically died in 1957. Shattered, the family left Rangoon and returned to India. His father then took up a job with the Burma Oil Pipeline Project, which took him to different places in Bihar and Bengal. Another tragedy struck the family four years later—his father died. Coping with the gaping holes in his family was hard enough; forgetting his beloved Burma made it harder on Karat. "I was used to a certain way of life—a placid, quiet life," he says. "It took me quite some time to get used to the new life."

But that "feeling" which made him cheer the Burmese football team as a child hasn't quite left him. His current interest in Myanmar—he keeps in touch with Burmese students and activists involved in the restoration of democracy in that country—goes beyond the political: "I have a special empathy for the Burmese people. It's a rich rice-growing country, rich in natural resources and precious stones. Its people were exploited by their colonial rulers and by Chettiar moneylenders."

So has he been back? "Burma is a country which doesn't leave you," says Karat. "I always wanted to go back—and I finally managed to do so as a tourist, on a private trip, only as recently as 2002. Once I landed there, it all came back to me. I took a taxi straight to the Aung San Stadium and from there directed him to the railway enclave I had lived in as a child. But sadly, today, all but one of those old wooden bungalows has been pulled down." Describing his five-day-long personal pilgrimage to the land of his birth as "fantastic", he says, "Rangoon city has not changed much—it still retains its old-world charm. I visited the lakes, Mandalay, the temples in Bagan on the Irawaddy. And Bahadur Shah Zafar's tomb, where I left a donation." And that was how a commissar paid homage to an emperor.