For what is still notionally an anti-corruption party, I thought this was the nadir: give a Rajya Sabha seat to a millionaire who had recently defected from the Congress—that, after striking a deal on getting him nominated to Parliament. What’s more, the man, Sushil Gupta, is also part of an “education mafia”, as termed by Manish Sisodia, a leader of the very party, AAP.

But the slide didn’t end there! Just one-and-a-half month thence, after the midnight of February 19, two legislators of the ruling AAP assaulted none less than Delhi’s chief secretary (CS). The MLAs, Amanatullah Khan and Prakash Jarwal—both have a criminal record—manhandled Anshu Prakash after the soft-spoken IAS officer was summoned to the residence of chief minister Arvind Kejriwal.

A third of the 21 cameras in the venue were shut down, yet I believe the ruckus wasn’t pre-planned. It might have happened on the spur of the moment, with Kejriwal raising his voice and telling the CS that the CM was the unchallenged malik of the National Capital Territory. At this, the top bureaucrat might have averred he is answerable only to the Lieutenant General. That may have incensed some hotheaded MLAs.

The CM should have immediately realised the gravity of what had happened. He should have called the media, accepted the mistake and sought action against his MLAs. Instead, what happened was actually Kafkaesque: the outdoor CCTV cameras suddenly developed an error or were doctored suitably to show a delay in the exit of Prakash, who later alleged assault. That ‘time gap’ of 40 minutes and 42 seconds is something the AAP concocted to ‘prove’ that the CS was ‘lying’. It was for this the party held a press meet. For that twist in the tale, the government came up with this false camera records and a fake statement. To me, the worst part of the episode was when the AAP played the Muslim and Dalit cards for the ‘victims’, Amanatullah and Jarwal. Never have even a Mayawati or Laloo Prasad Yadav sunk to such lows. Overall, communal and caste politics, lies and fabrication from a ruling party whose own leaders assaulted a senior civil servant!

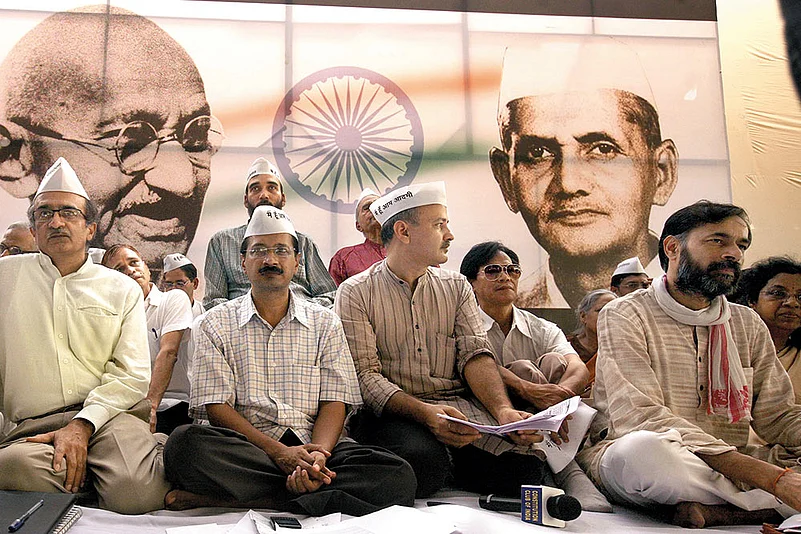

So where did the fall begin? Are there specific events that saw the APP slide from being a moral, ethical and even revolutionary party formed to fight social and administrative maladies? At what point did things go wrong for the ‘idealistic’ party that was formed (in November 2012) on alternative politics based on participation, accountability and decentralisation? Let me recount a few events:

- The loss in the 2014 general elections, where the nascent party accepted senior ideologue Shanti Bhushan’s suggestion and fought over 400 Lok Sabha seats, creating unrest and sullen anger down the ranks. Kejriwal started questioning the logic of listening to Bhushan, his lawyer-son Prashant or Yogendra Yadav, another founder-colleague of the AAP. The seeds of distrust were sown. Kejriwal, in his mind, was busy calculating the usefulness of all three; he had begun considering them to be redundant.

- In the December 2013 Delhi assembly elections, the AAP won 28 seats, BJP 32 and the Congress 7. After the AAP government exited in mid-February 2014, we were waiting for re-elections. That was when the BJP had begun trying to win over some of the Congress MLAs in a bid to form government. That unnerved Kejriwal and his small team of advisors. They decided to approach the Congress and re-form the government in partnership with that party. The AAP leadership was uncomfortable while being out of power. They were not willing to stay on their principles and wait for the next polls.

- The impatience led them to take questionable decisions. For instance, it was overriding democratic decisions by the AAP’s own Political Affairs Committee (by a 5:4 vote) that the party joined hands with the Congress. Luckily for many, the Congress did not agree to the AAP offer. That was when I first raised my antenna of suspicion against my party.

- Then, during the 2015 Delhi assembly elections, the AAP decided that “winnability” of candidates was more important than their earlier focus on principles. The desperation to win somehow marked a moral descent. Alternative politics was put aside for electoral power. Outside the AAP, not many knew that this was no longer the same party. The Delhi electorate had given the party massive support, believing it was honest—that’s how it won the February 2015 elections with unprecedented margins. But the party had started corroding from within.

- Prashant and Yogendra were upset that so many compromises were being made. They kept on raising these issues within the party. Kejriwal and his team decided to discard them, considering that these two leaders could not influence too many votes. Such was the snub that, as one of the leaders said, it “set an example for none later to have the guts to ever raise a voice contrary to Arvind’s”. So, the party became one of the biggest proponents of two things against which had initially fought: authoritarianism and arrogance.

- Having won Delhi by such huge margins, it grew eager to capture India. So, that became the next target even as the party was completely unprepared for such a task: it had no organisation, management bandwidth or understanding of national politics. The strategy drawn was to take on Prime Minister Narendra Modi at all levels.

- The BJP had, in summer 2014, won with 31 per cent of the country’s votes. The AAP wanted to become the magnet for the balance 69 per cent. Therefore it took certain decisions: attack the PM three times a day, fight against him in the Varanasi polls, call Modi a coward and a psychopath, allege that the PM was planning to kill Kejriwal (so as to show the AAP leader as the BJP’s worthy opponent). The AAP had neither organisation nor workers across the nation; therefore it went on to plan a weird 2019 election strategy—somewhat on the lines of a presidential contest.

- The AAP decided that a ‘Modi versus people’ mantra was to be created with a plethora of opposition leaders in a grand anti-BJP alliance without the Congress. The plan was to cobble up a coalition with regional satraps like Mamata Banerjee, Nitish Kumar, M. Karunanidhi and Navin Patnaik. But two things happened. One, the JD(U)’s Nitish dramatically supported the BJP-led NDA. Two, the AAP, contrary to its hope, lost in the 2017 Punjab elections. Together, they jeopardised the party’s desire to lead an imagined mahagathbandan. Attempts are still on to create this line-up: the RJD’s Laloo (before he went to jail) and son Tejashwi Yadav met Kejriwal four times. The AAP founder should have just focused on giving good governance in Delhi and creating an administrative model. Instead, he was in too much of a hurry to become a national alternative.

- When it fought in Punjab in February last year, the AAP knew it was a big state used to electoral tactics on caste and communal lines. Far from attacking them, the party found these as the only way to succeed—only to ultimately lose the polls. “We” were fast becoming “them”.

Having mishandled the official funds the party got to fight the elections honestly, the AAP had no option but to remove the donation list from the website. The final fig leaf was off even as volunteers, supporters and even donors were aghast. Money stopped flowing, coffers became empty. Then, much like a gambler who has already lost, the party decided to fight more and more states: Gujarat, Goa, Manipur, Nagaland and Karnataka—with disastrous results. From where is the money to come for the party to fight these expensive elections? That is when it was forced to compromise with the likes of Sushil and N.D. Guptas. Now, on top of it all, the ugly CS incident.

In any democracy, a constant foul-mouthed confrontation with our own administrative tools is just the way towards disaster. Calling the L-G a chaprasi (peon), dalal (middleman) or chor (thief) cannot ensure you cordiality, leave alone smooth functioning. Using foul language against a duly elected PM cannot assure you support from the Centre. They will surely use that power against you if you provoke them—unlike your ex-partymen who you humiliated. The AAP mulishness has let down the people’s mandate. How will this party in Delhi deliver governance without the support of the administration for the next two years? Why would the NCT’s citizens again vote for the party that cannot deliver governance?

The AAP has someone very self-destructive at its highest decision-making. I cannot see a way by which the party and the government can redeem itself, unless it apologises to the bureaucrats. It is still not too late to redeem themselves, but, for that, one has to have the strength of character and an ability to transcend one’s ego. Will they?

(The writer was a member of the national executive of the AAP. His AAP & Down: An Insider’s Story of India’s Most Controversial Party is a best-seller.)