The desire to have normal relations with Pakistan has long dominated the Indian foreign policy establishment. It was a constant obsession with Jawaharlal Nehru, who took over the reins of newly partitioned India, and several prime ministers who succeeded him. But three wars and generally hostile relations between the two countries over six decades have seen only three Indian prime ministers visit the estranged neighbour in any sort of proactive bid to improve bilateral ties. Ditto for Pakistan; the army generals or the civilian leaders who have run the country have had few occasions to come to India on official visits. More often than not, such trips have been couched as side-shows to a cricket match, or stopovers on a pilgrimage, as Pakistan President Asif Ali Zardari did last Sunday in Delhi.

The Bhuttos and Zardaris are believed to be great followers of pirs. The Pakistan president has a resident pir at the Awan-e-Sadr, the presidential house in Islamabad, who guides him on matters personal or political. He is also known to sacrifice black goats at regular intervals to tide over various crises. The joke in Pakistan is that were he to get a second term in office, there won’t be any black goats left in Islamabad. Zardari’s coming to India for a visit to Ajmer Sharif was thus of a piece with his divine inclination. Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s ‘graciousness’ in hosting him for lunch afforded an unscheduled, informal chance to the two leaders to discuss the entire range of issues on the bilateral track, besides exchanging views on other regional and global developments.

At the end of their talks, the Pakistan president in reciprocity revived the invitation for Manmohan to visit Pakistan. But no sooner than such a proposal came up that views on the subject started pouring in from various quarters in India, with some even wondering whether Manmohan should go there at all.

“While Zardari could describe a working visit as a pilgrimage, no such subterfuge is available to the prime minister,” K.C. Singh, former secretary in the MEA, told Outlook. “This is because the condition precedent to Manmohan Singh’s visit will have to be credible action by Pakistan on the 26/11 perpetrators, particularly Hafiz Saeed.”

The monster of terrorism has indeed loomed large over Indo-Pak ties, with India having been at the receiving end of terror attacks originating from Pakistan for decades now. But never did it hover as sinister as it did after the 26/11 attacks in Mumbai four years back, which millions of horrified Indians watched unfold in gruesome detail on their TV screens for three days running. Mumbaikars and the rest of India resumed normal life soon thereafter, but normality went on long leave from the Indo-Pak relationship. Few in India are willing to forgive or forget the Indian state’s helplessness in the entire sequence of events then, while the tardy process of trial of the 26/11 planners in Pakistan now has only heightened misgivings about Pakistan’s sincerity of intent. America’s $10-million bounty on Hafiz Saeed’s head on the eve of Zardari’s visit has further served to bring the issue back into sharp focus.

Few Indians would expect Pakistan to hand over Saeed or the 26/11 perpetrators. But the cynics now only grow in voice and number each time there’s talk of improving and normalising relations with Pakistan. “It should not just be an occasion for a photo-op where the real issues are brushed under the carpet,” says Leela Ponappa, India’s former deputy national security advisor. Since politics in Pakistan has not yet come together, she thinks the “elephant in the room continues to be the Pakistani army”.

| “If the PM goes to Pakistan, it has to be a substantive visit. But Pakistan too has to reaffirm it won’t allow terror on its soil.” Yashwant Sinha, Former foreign minister |

| “While Zardari could describe a working visit as a pilgrimage, no such subterfuge is available to the prime minister.” K.C. Singh, Former secy in the MEA | ||

| “Hafiz Saeed is a sore point, but do we want the most extreme elements in Pak to dictate the scope of our engagement?” Srinath Raghavan, Centre for Policy Research |

| “Manmohan has been in power since 2004, and every Pakistani leader has invited him, but he has not come.” Riaz Khokar, Former Pak foreign secy |

| “Manmohan’s visit can be a CBM if it’s without any preconditions. Else, any Pak govt will be suspected of appeasement.” Shireen Mazari, Vice-president, Tehreek-e-Insaf |

Others too dig in their heels to say the Indian PM should go to Pakistan only if Islamabad does what India wants it to do. Former Indian foreign secretary Kanwal Sibal lists out some of the conditions which might satisfy India, but it also seems unlikely that Pakistan would act upon them. “Will they take Hafiz Saeed out of the equation? Will they proscribe the jehadi groups operating from Pakistani soil? More importantly, will they take any meaningful action against the perpetrators of 26/11?” he asks rhetorically.

But any precondition to a Manmohan visit to Islamabad is anathema to political parties in Pakistan. “His visit can be an important confidence-building measure if it is without any preconditions,” says Shireen Mazari, vice-president of Imran Khan’s party Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, which is fast gaining ground in Pakistan. “Otherwise,” she adds, “it will have little value and will make it difficult for any government in Pakistan to move ahead without being suspected of appeasement.”

South Block officials too are against setting preconditions, even as they acknowledge that 26/11 remains an important issue in Indo-Pak talks. They point out that if Pakistan makes progress on Kashmir a precondition for talks, Indians would strongly oppose it. What little headway was made with Pakistan was only after the two sides agreed that it would be foolish to make any one issue central to their engagement. Terrorism from Pakistani soil has by no means taken a backseat, but rather than making it a stumbling block, a better way would be for India to convince its neighbour that terrorist activities are harmful for bilateral ties and ultimately hurt the country that sponsors terrorism—as the case is turning out to be in Pakistan.

“We seem to have placed too much premium on the symbolic significance of dialogue, which is not very helpful,” Srinath Raghavan, strategic analyst with the Centre for Policy Research in Delhi, told Outlook. “It would be better to present dialogue with Pakistan as part of normal diplomacy.” He thinks it is important to have reliable channels of communication even in times of crisis. “Dealing with Pakistan will require a more sophisticated mix of negative and positive levers to shape its behaviour.”

But what levers does India have to deal with Pakistan? Some argue that Pakistan should be told in no uncertain terms that any future terror attack on India might be met with armed retaliation. But this could well lead to a war with unknown consequences and might prove costly to India as well, derailing its economic growth and development. It would be the last resort for the Indian leadership.

Then there are others who think the desire to normalise relations with Pakistan is a ‘north Indian’ obsession. P.V. Narasimha Rao, who was from the south and enjoyed a full five years as PM, expressed no such inclination. Nehru and Rajiv did, and Vajpayee was almost making a habit of it. Manmohan, who dreams of a peaceful and stable South Asia, also leans in that direction.

And while there is ambivalence within the Congress on Manmohan’s visit, the BJP is not totally against his visit, given Vajpayee’s overtures during his tenure. “If the prime minister goes to Pakistan, it has to be a substantive visit,” says former foreign minister and BJP leader Yashwant Sinha. Agreements on Sir Creek, Siachen and trade liberalisation could help achieve that. But he also wants Pakistan to act against terror groups and the 26/11 perpetrators. “Pakistan will have to reaffirm the commitment it made to Atal Behari Vajpayee in 2004 not to allow its soil for terrorist activities against India,” says Sinha.

Raising Pakistan’s stakes by strengthening economic trade ties—much like India and China have done—could be another alternative. “The trade potential is so huge that any step India takes with Pakistan on this will transform the relationship,” says C. Rajamohan of the Observer Research Foundation. This could expand the constituency for peace in Pakistan and minimise the chances of future terrorist attacks on India.

While India debates Manmohan’s proposed visit to Pakistan, many in the neighbouring country remain sceptical on the eventuality. “He has been in power since 2004 and every Pakistani leader has invited him, but he has not come,” says former Pakistan foreign secretary Riaz Khokar. “Maybe he is politically too weak to take any bold decisions,” he goes on to say, making light of India’s demand for action against 26/11 perpetrators. “Maybe Zardari has charmed him or maybe Hafiz Saeed will be gifted on a silver platter.”

The question then remains: should Manmohan go to Pakistan whether or not it hands over Saeed or others to India? “Hafiz Saeed is a sore point,” says Raghavan, “but do we want the most extreme elements in Pakistan to dictate the scope of our engagement with it?” The future of the Indo-Pak relationship rests now on Manmohan Singh’s answer.

Pilgrim’s Progress

Since Partition 67 years ago, only three Indian prime ministers have visited Pakistan so far

Jawaharlal Nehru Visited the country first on April 26, 1950, 18 days after the Nehru-Liaquat Pact on minorities was signed in New Delhi. He visited the country again in September 1960 to sign the Indus Water Treaty with Ayub Khan. The water treaty holds even today.

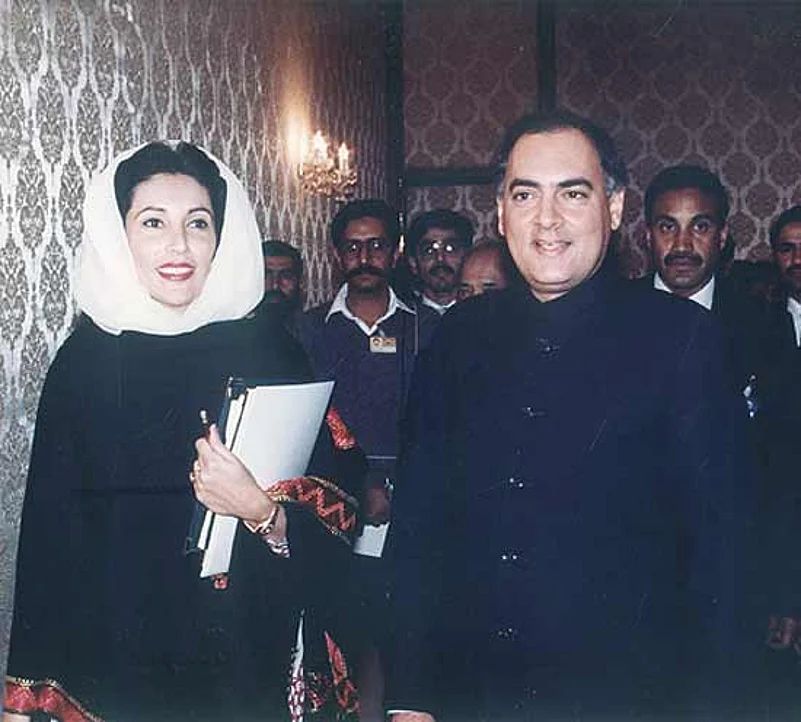

Rajiv Gandhi In July 1989 to hold talks with his Pakistani counterpart, Benazir Bhutto. The meeting of the two young leaders led to the end of militancy in Punjab but the subsequent months paved the way for increased militancy in Kashmir.

Atal behari Vajpayee In Jan 1999 on the ‘peace bus’ to Lahore for talks with Nawaz Sharif and in Jan 2004 for talks with Pervez Musharraf. The first initiative ended in the Kargil conflict, though Musharraf’s commitment to end terror from Pakistani soil towards India held for a while.