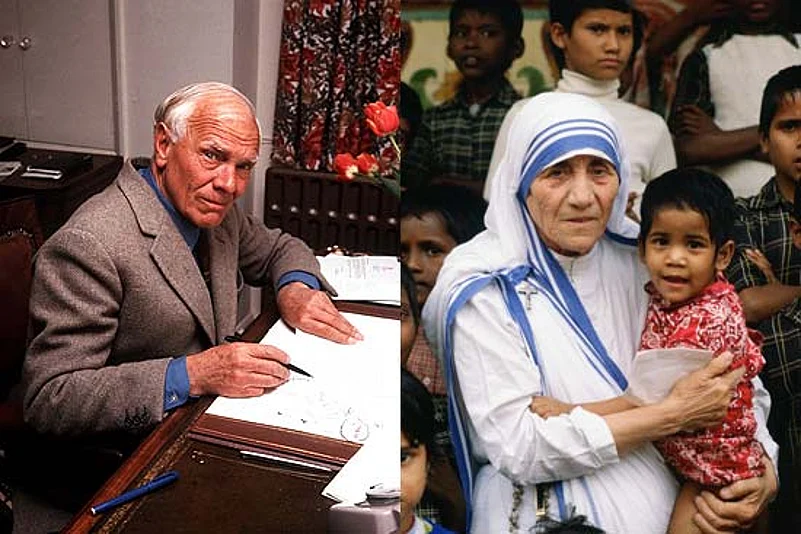

Malcolm Muggeridge (1903-1990)

‘Journalist, author, broadcaster, soldier-spy’

- 1925-27 Taught English in India

- 1932 Correspondent for Manchester Guardian at Moscow

- 1934 Penned a novel Winter in Moscow

- 1936 The book The Earnest Atheist gets him recognition

- 1940 Enlisted with Military Police at the outbreak of the Second World War; soon shifted to the intelligence wing

- 1946 Joined the Daily Telegraph

- 1949 Appointed editor of Punch

- 1969 His film Something Beautiful for God is released

- 2008 Posthumously awarded the Ukrainian Order of Freedom

***

Twenty-four years after his death in 1990, and 17 years after hers in 1997, broadcaster and writer Malcolm Muggeridge and Mother Teresa, whom he familiarised to the Western world through his writing, are back in the news at the same time. Recently, RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat caused outrage by alleging that Mother Teresa served the poor only because she wanted to convert them to Christianity. Muggeridge was dragged into the news by a new book, Pinkoes and Traitors: The BBC and the Nation—1974 to 1987, by BBC historian and media professor Jean Seaton. It alleges that the legendary writer was a “serial groper” and abused his authority to molest women.

In a letter to the Daily Telegraph, Muggeridge’s niece Sally Muggeridge acknowledged that her uncle was “anything but a saint in his first 60 years”. She wrote that he had been nicknamed ‘The Pouncer’ and nsit (acronym for ‘not safe in taxis’). But, she added, his well-publicised conversion to Christianity, in no small measure due to his encounter with Mother Teresa, had been truly life-changing. After that, Muggeridge adopted austere living and gave up meat, smoking, drinking—and yes, even sex.

Of late there has been a spate of exposures of celeb TV and news personalities—many of them facing allegations of serial molestation of women through misuse of authority or their position and influence. Seaton’s book lets off Muggeridge and Sir Huw Wheldon, a top BBC broadcaster and executive, relatively lightly, describing them as gropers. But another former British TV presenter, Jimmy Savile, has been accused of raping 34 women and of “126 indecent acts”. An eccentric TV personality, he was also known as ‘Saint Savile’ for raising 40 million pounds for charity. While London’s Metropolitan Police has been investigating the cases, a 45-year-old woman came forward this week and offered to undergo a DNA test to ascertain if her grown-up daughter had been fathered by Savile. The long and sordid list includes Irish film and TV actor Wilfrid Brambell, American-British TV presenter Paul Mathew Gambaccini and others.

It was in 2011, after the death of Savile, that the truth about the misconduct of some of BBC’s most “high and mighty” patriarchs started coming to light. By 2014, nearly 60 cases of sexual harassment came to light against Savile. The Savile trials in turn emboldened other victims to lodge complaints against top BBC bosses.

A former BBC employee claimed that she was molested by presenter Dave Lee Travis when she was a 17-year-old trainee. According to a report by John Twomey in the Express, “The alleged victim told the jury, ‘During that time I just got on with it. You had to get on with it. There wasn’t anybody to talk to about it. The more time I spent at the BBC, the more I realised it was common practice to have tongues down your throat, tongues in your ear, bums being squeezed.”

On condition of anonymity, a BBC editor told Outlook that the idea was, if you can come out to work, you should be ready to do what it takes to come out to work. “Men were still not used to the reality of seeing women on an equal footing with them and here was a situation where these vulnerable young women were at their mercy and the men just went berserk,” she said.

In her book on the BBC, Jean Seaton (Right), a media historian, shines the light on widespread sexual harassment by men at the top.

Muggeridge worked for the Statesman in Calcutta as a deputy editor in the forties. But he first met Mother Teresa in 1967, when he interviewed her for the BBC. The interview did not excite the editors much and it was eventually telecast late on a Sunday night, a low-viewership slot. But the response was overwhelming, with viewers sending in cash, cheques and letters saying that nobody had spoken to them as the quaint Albania-born nun had.

He returned to Calcutta in 1968 to film a documentary on the nun. While the unit apparently wanted to shoot for six weeks, it is said Mother Teresa allowed them just five days. During the shooting, the cameraman told Muggeridge it was impossible to shoot in a dark room with little or no light. Egged on by Muggeridge, he did finally shoot and when the film was developed the room appeared suffused with what Muggeridge called a ‘divine light’. The time he spent with her apparently convinced him, an agnostic, to convert to Christianity. The film, and his book Something Beautiful for God were followed by another book, Jesus Rediscovered. But if Seaton’s revelations are taken at face value, the conversion failed to curb his predatory sexual instincts.

In her book, Seaton says top BBC staff were “known to proposition younger women, especially secretaries, for spanking sessions”. She says Huw Wheldon and Muggeridge were both gropers, though so were most other men in most other British institutions then. The term ‘sexual harassment’ did not exist then.

In Calcutta, veteran city journalist Tarun Ganguly, who was with the Statesman for a number of years, says the allegations against Muggeridge may not be entirely baseless, but the subject was rarely discussed at the time. “In those days such matters were rarely reported. Though I joined after he left, his reputation was that of a sound journalist who cycled to work and wore spotlessly clean white shirts and trousers. His personal indiscretions, if any, were never discussed,” Ganguly says.

Mother Teresa’s close aide Sunita Kumar recalls an interaction with Muggeridge 30 years ago. She’d been volunteering with the Mother, who once asked her to deliver a letter to Muggeridge when she was going to London with her husband Naresh Kumar, the tennis player. She says that unfortunately, owing to a match at Wimbledon, she could not meet Muggeridge, though she spoke to him on the phone. “I have no reasons to doubt Seaton’s allegations, but I can tell you that even if they were true, it would not have stopped Mother from trusting in him. She always said, ‘Forgive, forgive, forgive’. In her eyes, no one was a sinner.”

Indeed, it is said about Muggeridge in Calcutta that he was a deeply dissatisfied man: by his own admission, he had attempted suicide at least once, and he was constantly groping in the dark for answers—until he met Mother Teresa. His life was marked by many sharp turns. He abandoned atheism and leftist ideology, growing disillusioned with Communism. Towards the end, he was a devout Christian and swung towards the right-wing.

Does the new book zero in on merely a phase in Muggeridge’s life, in which he and so many of his colleagues found that in the “material world”, which he so vehemently spoke against later in his life, depended for its pursuit of happiness on exploitation and abuse of power? Why else would he write: “The pursuit of happiness..tends to involve...trying to perpetuate the moods, tastes and aptitudes of youth.” And why would he state with as much conviction, “One of the many pleasures of old age is giving things up.” Men with great gifts seem to be packaged with even more serious flaws.