- Man, girl killed, in landmine explosions in Sui and Kohlu

- Unidentified men blow up gas pipeline, supply to Pir Koh gas plant disrupted

- Five people shot dead in Quetta, Dera Murad Jamali

This is just a sampling from a litany of page-one headline news from trouble-torn Balochistan, and they are laden with the misery of nameless, faceless Pakistani citizens. Balochistan, seething under a long-running secessionist campaign, has boiled over in recent months with ethnic strife and brutal army action. Missing, though, from the news columns are the daily kidnappings for ransom, and scores of tortured and bullet-riddled bodies dumped by the wayside. Settlers from Punjab and Hindus, as it’s well-known, make easy prey for Baloch nationalist extremists.

As became evident at the recent US congressional hearing—where many speakers stressed the Baloch “right to self-determination”—Balochistan is also the frontline of the new Great Game, with Pakistan resisting US pressure to set up consulates there. It fears the US would try to destabilise Iran through the Jundullah—a pro-Baloch, Iranian religious group with alleged CIA links—which operates on the Pak-Iran border.

The frontline is also in Islamabad. Camped for two weeks before the majestic buildings that house the president, prime minister, Parliament and the Supreme Court, a group of men, women and children—among them a month-old infant—huddle together in below-freezing temperatures. They are the near ones of the swelling ranks of ‘missing persons’ from across the land, but mostly from Balochistan. Their numbers grow by the day; the government remains unmoved.

“We will die here or return with our beloved ones. Those responsible for this cruelty should be exposed,” Amna Masood Janjua, chairperson, Defence of Human Rights, told Outlook. Only stray, expected voices rose in support. London-based MQM chief Altaf Hussain criticised PM Yousuf Raza Gilani’s call for an all-party conference for “collective thinking” on Balochistan. “You are dumping their corpses every day, yet want them to remain loyal,” he said.

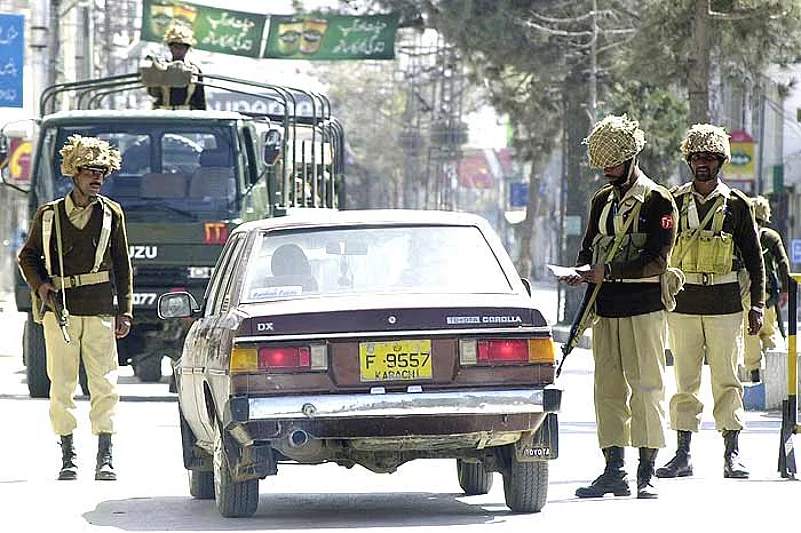

Baloch nationalist tribals. (Photograph by AFP, From Outlook, March 12, 2011)

The plight of the wronged in Pakistan’s largest but least populated province might not register on Islamabad’s radar, but its untapped mineral wealth—oil, gas and copper—and its strategic significance, bordering as it does Afghanistan and Iran, lends it great importance. Balochistan’s Gwadar Port on the Arabian Sea, a mere 120 km from the Iranian border, sits close to the busy oil-shipping lanes to and from West Asia. No wonder China has long eyed the province—its firms have conducted mining operations there. Pakistan is reportedly keen on Beijing setting up a base at Gwadar.

Even as poor Balochis in the interior huddle together in the bitter cold at night for warmth, Balochistan’s reservoirs supply piped gas from Sui to homes and industries nationwide. The under-construction Iran-Pakistan gas pipeline will also run through the state. While foreign firms vie among themselves for contracts here to explore oil and gas, and mine minerals such as gold, copper, limestone, barite, marble and chromite, central apathy ensures that Balochistan’s natural wealth has yielded no benefit to Balochis. Clearly, a terribly myopic policy has blighted a province that could have been Pakistan’s goldmine and hosted its Dubai.

Together with corrupt Baloch sardars and an insatiable centre, the military establishment rules Balochistan with an order so repressive that the khaki is as hated as it was in former East Pakistan. The roots of the current bloodletting can be traced to the killing of Baloch nationalist leader Nawab Akbar Bugti in 2006 that fed fresh tinder to the embers of the freedom struggle.

Bursting with fractious strife, bloodied at every corner, Balochistan is ripe for a clean breakaway. Already the crescent and star of the national flag has been replaced in areas, while the national anthem has been banned in some educational institutions. Six decades of repressive rule and several military operations are more than what proud Balochis could bear, and with matters coming to a head in recent months, the nationalist cause is gaining popularity, and many sympathisers offer refuge (and arms) to rebels as they take on the state.

As a weak democratic set-up bears mute witness to the military’s repressive tactics, there were, till recently, few signs of a let-up from the establishment. That came last week, after the shock the US congressional hearing delivered Pakistan, when interior minister Rehman Malik offered amnesty to exiled leaders of the insurgency like Brahamdagh Bugti (Akbar Bugti’s grandson) and Hyrbyiar Marri, and urged them to return and sit at the negotiating table with other Baloch nationalists and the centre. The offer was turned down by Baloch leaders.

“What is the point of more talks? First create an environment conducive enough for us to sit at the table,” pleads Hayee Baloch, head of the National Party. The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan has called for the immediate demilitarisation of Balochistan as the first confidence-building measure towards a political dialogue. It has warned that if corrective actions, in agreement with the Balochis, are not taken, the country may dearly regret the consequences.

“The existence of checkposts causing inconvenience and humiliation was reported by people all over Balochistan.... personnel manning these checkpoints insulted the people by shaving their moustache, tearing the Baloch shalwar and making other gestures derogatory to their culture,” notes the HRCP.

The separatist movement itself, meanwhile, has evolved. A younger generation has taken over from the older sardars; media-savvy separatists now fight for their cause from world capitals. Traditionally, it was Afghanistan and the Soviet Union that provided funding and safe havens to Baloch separatists. India and the United States followed in their footsteps, and Europe openly provided visas and asylum. In 2009, amid loud applause in Pakistan, Balochistan was mentioned in the joint statement of the PMs of Pakistan and India at Sharm-el-Sheikh. It was duly claimed as a tacit owning up of Indian interference.

Some years back, at a meeting between then president Pervez Musharraf and Afghan president Hamid Karzai, the general presented evidence of Afghan help for Brahamdagh Bugti, leader of the Baloch Republican Party. Karzai denied the charge, but as the two countries went into a tactical embrace, Bugti was asked to leave Afghanistan, though he was never really denied assistance. “I first went to Kandahar, then relocated to Kabul. The Afghan intelligence head treated me like a brother and kept me safe from several assassination attempts,” Bugti later remarked in Geneva.

Leaders from various Baloch tribes appear regularly on the electronic media, with a defiant Mir Mehran Marri telling Express TV, “If India was helping us, Balochistan would have broken away a long time ago”.

And holed up in London is Mir Suleman Daud Ahmadzai, the present Khan of Kalat, who, together with US congressman Dana Rohrabacher, managed the latest coup in rekindling the Baloch cause. In a hearing of the US House Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations that palpably shook Islamabad, witnesses detailed human rights abuses, and US lawmakers stressed on the Baloch right to self-determination. While Islamabad shrugged it off as “foolhardy global vigilantism”, Ahmadzai retorted: “I have told the US Congress about our situation with Pakistan since 1947, the human right violations and the military operations, including the occupation of our sovereignty.”

Usman Khalid, chairman of the pro-Pakistan Rifah Party, advocates a solution from the other extreme: “The most effective response to treason and rebellion is decapitation. Pakistan hesitated in East Pakistan in 1971 and it is hesitating now. It is counter-productive to kill hundreds; it is best to deal with leaders as was done with the Khan of Kalat....”

Akhtar Mengal, former Balochistan chief minister, argues with cogency and reason: “Why are Pakistan’s rulers criticising the word ‘self-determination’ when they use the same slogan for Kashmir?” Balochistan, assailed by outside forces, fought over by nations across the seas, and collapsing by the day from within, is near the end of its tether. It needs urgent life-support.