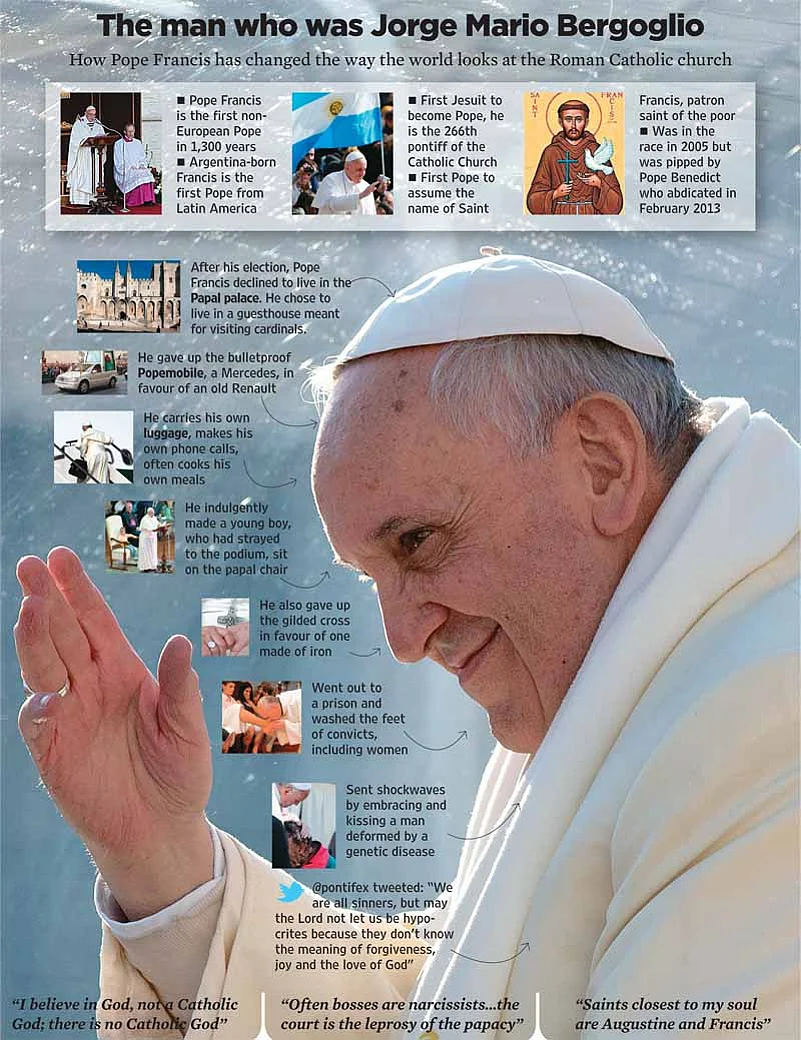

The analogy with a recently seen balcony apparition in New Delhi perhaps goes beyond the visual: you might be forgiven for thinking India’s aam aadmi metaphor had travelled a hemisphere or two across the Holy See, so to speak, and reached the Vatican’s gilded halls. It’s the same willing diminution of the self, while realising a role traditionally defined by grandeur. The same self-conscious belittling of ‘leadership’, and its recasting in the more democratic and homely raiments of the ‘commoner’. In this case, however, the dead earnestness is lightened by a partly jokey roleplay. Witness this scene, almost out of a comic morality play. Soon after he was elected Pope, Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio appeared on a balcony at the Vatican and told the assembled faithful that the cardinals seemed to have gone to fetch the new Pope from the end of the world. Muffled laughter greeted him before realisation dawned that this was indeed the new Pope speaking. That little joke set the tone of his papacy. The rest flowed logically. He avoided the bulletproof Mercedes known as the Popemobile, hopping onto a mini-bus with “the guys”, the cardinals, to travel back to the guesthouse. And when he raised a toast later in the day, he wryly told them, “May God forgive you...I hope you do not regret this later.”

That was in Spring 2013. With a beginning as auspicious as that, it’s no stray miracle that, by Christmas, Pope Francis I had a number of firsts to his credit. He’s the first Pope to wash and kiss the feet of a Muslim. He’s the first one to say—Yes, there is a God, but there is no ‘Catholic God’. He is also the first to concede the possibility (hitherto considered remote) that Marxists, atheists and homosexuals can be “good people”. A compulsive “hand-shaker and baby-kisser”, a soccer fan who admits to loving a faster and tangier version of the tango, a film buff, an opera fan, a Dostoevsky and Borges lover, wonder of wonders, he has three million-plus followers on Twitter. He’s also topped Facebook’s trending topics of 2013, and is “man of the year” of not just Time but also of gay magazine Advocate. Who would’ve thought this possible in the dour, textbook days of Joseph Ratzinger, the German Pope? Make no mistake, Francis’s predecessor was a formidable scholar and an impeccable Catholic but the difference in style—and substance—between the two tells us as much about historical expediencies as about personalities.

Without a doubt, Francis is the one more alive to history and its possibilities. He’s just about the best Pope to have for a world fresh from the Occupy movement and democratic upsurges, a world freshly sceptical of capitalism’s claim to universal success. So it’s not just his 1984 Renault, nor his residence in the cardinals’ guesthouse instead of the papal palace, or his self-cooked meals, all worthy of the old Jesuit heritage of austere living. It’s also about actual theoretical critiques, pithily expressed, as in this one on the famous ‘trickledown’ effect. “The promise was that when the glass was full, it would overflow, benefiting the poor. But what happens instead is that when the glass is full, it magically gets bigger. Nothing ever comes out for the poor.”

Naturally, his unambiguous statements—in word and gesture—have the piquant effect of placing him politically on the left. A left-wing Pope? That would have been heresy in the days of Pope John Paul II. But the fact is, the world has rumbled along erratically for two decades after the ‘end of history’, and in this grim future, an acknowledgement of the meek prophesied to inherit the earth seems that much more tactically apposite. And thus it was that the Pope came to cop criticism for being a commie! Finding himself at the wrong end of a particularly pointed barb from US radio host Rush Limbaugh—who’s in a way the pope of the indignant right—Francis was constrained to defend himself. “I was not, I repeat, speaking from a technical point of view but according to the church’s social doctrine. This doesn’t mean being a Marxist.”

Yet there was no going back on simple human concerns. He once told an interviewer that “the two most serious evils afflicting the world today are unemployment of the young and the loneliness of the old”. The reply, to a question on the challenges before the Catholic Church, resonated across the world and especially in India, where half the population is under 25. Neither statesmen nor religious leaders, here or elsewhere, had given voice to the angst of the age quite so forcefully. A parish priest in an Italian town exclaimed that in over 35 years of service he had till now never witnessed people coming up to him on the streets to ask how they could be of some help to the poor, enough proof that the Pope’s words have found an echo. The pontiff has reached out to non-Christians and gays too, famously asking “Who am I to judge?” if a homosexual reached out to God. While the church remains opposed to same-sex unions and abortions, the shift is visible on the ground.Indeed, after the Indian Supreme Court upheld a 150-year-old law that deemed homosexuality a crime, Cardinal Oswald Gracias of Goa, one of the eight cardinals appointed by the Pope to advise him, asserted the church had never considered the gay community as criminals.

A former literature teacher, the Pope has a way with words and metaphors. His vision of the Church, he says, is that of a field hospital after battle. “We have a glut of problems to tackle...stop bickering and roll up your sleeves...don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.” First things first; contentious and divisive issues can be dealt with later.

His views on the free market are of special interest to India. “The assumption that economic growth would inevitably succeed in bringing about greater justice and inclusiveness in the world...has never been confirmed by the facts,” the Pope declared in his first apostolic exhortation, adding that the rich must help, respect and promote the poor. What dies every morning and is reborn each night ? The answer to the riddle is ‘hope’, reminds the Pope. It is a recurrent theme and by emphasising the role of the individual as well as institutions in renewing hope, he’s also made religion ‘cool’ again. Little wonder then that Francis I takes most votes for ‘Man of the Year’.