One look at China should convince all naysayers that everything is in the realm of the possible as far as bullet trains go. The trains depart from Beijing South railway station, located in the heart of one of the world’s most congested cities. The trains traverse every direction through vast swathes of what must have once been agricultural land. They attract everyone, from the super-rich (who occupy the scenic view compartments) to the rich (who inhabit the first class) to the ‘cattle class’ (who throng the second class). The trains, dozens of them plying this way and that, are invariably full. They connect distant parts of a country larger than India with ease. And they are almost always on the dot and in all their existence, accidents have been few and far between.

The bullet train hasn’t solved China’s problems (nor will it India’s) but it has propelled an ancient civilisation to the modern era faster than you can say wtatkal. What Eisenhower’s push for freeways in America did in the early 1950s, the bullet trains are doing for China in the 2000s.China currently has Japanese- and German-designed bullet trains, but their embrace by a Communist country is instructive for India as it mulls their possibility and utility.

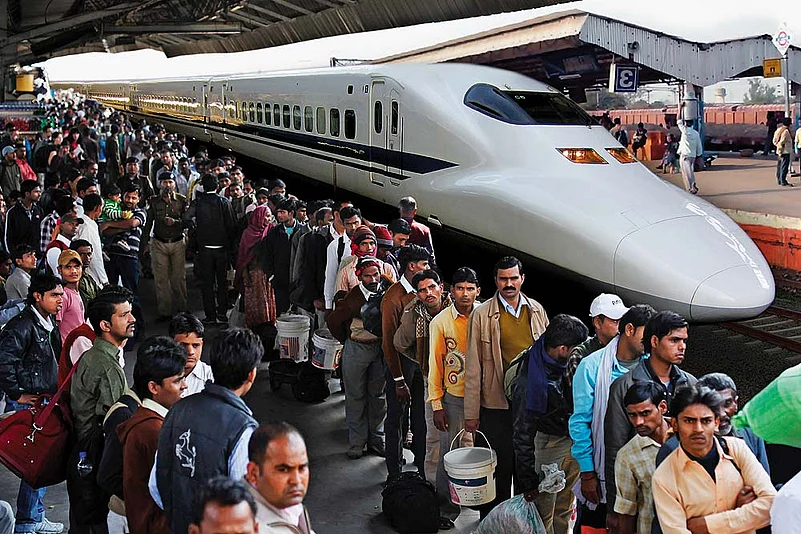

India has been seriously flirting with the idea of high-speed rail (HSR) for over a decade but is yet to go past the feasibility stage. The desire to see Indian Railway make the quantum leap to bullet trains even as large parts of the country await rail connectivity may seem incongruous, even undesirable, but the proposal is finally taking shape with Prime Minister Narendra Modi intending to make it one of his signatures to development.

Modi has got the Japanese and Chinese governments to commit investments in at least getting his dream Diamond Quadrilateral project off the ground. But for those banking on riding the first Indian bullet train to 2019 (when the next general election is due), expect to be disappointed. It will take at least 10 years to execute a single corridor. “Whether Japan or China, it’ll take at least 10 years whatever money you put on the table,” says a senior rail infrastructure official.

Union railway minister Suresh Prabhu, who is slated to present his first rail budget and vision of restructuring the largest rail network under a single authority later this month, is non-committal on the HSR network plans. “We’re still undertaking feasibility studies. The Japanese and Chinese are working on two of these studies. The Japanese will be submitting their study on the Mumbai-Ahmedabad route in June while the Chinese are doing a study of the Delhi-Chennai link,” says Prabhu. On the estimated costs or proposed tariff, he says it is too early to comment as the feasibility studies are yet to be completed and “many factors have to be considered”.

The average cost of setting up a bullet train infrastructure can vary from Rs 130 crore-Rs 150 crore per kilometre, with the completion costs raising it further. Initial estimates put the cost of just the 534-km Mumbai-Ahmedabad corridor at a whopping Rs 90,000 crore. Entry into Mumbai, while being most congested and thus most promising, is also very challenging. The envisaged 60 km stretch to Bandra-Kurla and Virar would have a lot of bearing on final costs, say railway experts.

They are, however, clear that for any HSR corridor to be of use to people, it has to come somewhere within the city. In the case of Mumbai, all the studies done so far show that while there is great potential, there are also multiple challenges, not the least being land issues. This, in fact, is a problem common to all HSR projects under study. “Physically, the plan is feasible, perhaps even easy given India’s topography. The difficult challenge to engineering feasibility in India would clearly be land acquisition, resettlement and fencing the row (right of way) from trespassers,” says Louis S. Thompson, a former World Bank expert and principal of Thompson, Galenson & Associates, who has done studies on restructuring railways in several developing countries, including India.

“Economic feasibility is a harder question. There will certainly be demand for HSR services, as India’s existing rail passenger demand patterns demonstrate,” Thompson adds, pointing out that Indian railways carry more passengers per km than any other railway in the world. Besides Modi’s Diamond Quadrilateral project comprising six corridors connecting the four major metros, including diagonally, seven other corridors have been proposed, of which six were part of the railways’ 2020 vision (see graphic).

Former railway minister Dinesh Trivedi feels land and safety issues (due to unmanned level crossings) are major constraints, and going in for elevated tracks or pursuing small corridors would be a doable proposition—though the return on investments would take longer. In response to a Parliament question, the rail ministry had last year revealed that a 2010 rites report estimated the internal rate of returns for the Mumbai-Ahmedabad HSR project at 9 per cent, operation and maintenance expenses at Rs 412 crore and total revenue of Rs 2,499 crore in the first year of operation, that is 2021.

Unlike the global norm, some stretches in the Diamond Quadrilateral project are longer than what railway experts consider the optimum desirable distance of 400-800 km that can be covered in two-three hours at 300 km per hour, says Devi Prasad Pande, former member (traffic) of the Railway Board. “The proposed Delhi-Chennai corridor does not make sense as it would have a running time of 10 hours or so,” says Pande. At the same time, the former railway official is confident that on shorter corridors entailing a two-three-hour ride, “the clientele will be willing to pay for the time saved by travel in a high-speed train as it makes for greater convenience and business sense even compared to air travel.”

Transport experts share the view that India would have to adopt a mixed fare model with some trains running point to point and others having a few halts, as in France. This could see first-class fare priced equal to air travel, second-class a bit lower than air and third-class equal to second-class AC travel.

Of course, the bullet train doesn’t come cheap. Look at China. It costs a lot to set them up and the ticket fares compare with airlines. A one-way first-class ticket from Beijing to Shanghai costs about Rs 10,000, but a second-class ticket is also available for half the price. Beijing-Shanghai is roughly the same distance as Delhi-Mumbai. While a Rajdhani Express does the distance in around 17 hours, the ‘G’ trains do it in five-and-a-half.

Many feel India shouldn’t go in for HSR when there are other pressing issues to be addressed, be it poverty reduction, malnutrition, employment generation or better rural connectivity by ordinary rail. But transport expert G. Raghuram, Public Systems Group, IIM-A, says there will be a trickledown effect on the economy. “We must definitely explore and get it in place in at least one route to demonstrate to the country what is possible. In terms of spurring business, it would have a lot of potential. There would also be gains because of technology inflow, construction activity will spur use of steel and cement, the use of high-quality rails and signalling will percolate to the whole system,” says Raghuram.

Transport economists say that, as in Japan, the outcomes cannot be measured only in terms of profitability of a rail network but also the economic returns, as faster travel and better rail connectivity make for better urban development. The Delhi Metro, its glamour quotient apart, has improved urban connectivity.

The biggest challenge is to do it right—where to locate the station, how many stations to have and the pricing model. More importantly, before getting on the bullet train, we need to get a fix on safety aspects and modernisation of the existing network that has been begging for attention for some years now. One option would be to enhance train speeds by strengthening the present infrastructure at one-fourth the cost of setting up a new dedicated HSR infrastructure. This work has already begun—the first of the semi-high-speed trains, Gatiman Express, on the Delhi-Agra route, is awaiting a green signal from the Commissioner of Railway Safety. Trial runs have shown that the running time will be reduced to 106 minutes, lopping off over 20 minutes.

While India still ponders the efficiency, utility and safety of the bullet train, China’s already taken the next leap forward. The world’s first and only commercially run magnetic levitation train (the MagLev, which theoretically can do a top speed of 431 kmph) runs between Longyang Road and the Pudong International Airport in China. A museum below the station charts the course of the MagLev from the ’40s. That China wants to showcase the MagLev tells us how mass transport at and beyond the speed of an F1 car can symbolise a nation in a hurry to reach somewhere.

***

Fast Life, No Pain, Now It’s A Bullet Train...

It is going to be expensive, with cost estimates running into over Rs 1,00,000 crore initially. It will also take at least 10 years to execute a high-speed rail (HSR) corridor. But India is going ahead. Here’s a look at the plans, pros and cons.

- 150 km/hr Maximum speeds, Rajdhani, Shatabdi

- 160-200 km/hr semi-high speed trains

- 300+ km/hr high-speed rail

The Pros And Cons

- India is looking at funding from Japanese and Chinese entities for pushing forward the implementation

- France is keen to undertake both semi-high speed and high speed projects but has made no offer of funding

- Land acquisition will be a major challenge for setting up separate tracks where high speed trains can operate

- Closer the start and end point is to the city nerve centre, more the cost of bullet train project

- Cost is a big factor; worldwide most bullet train projects are making losses even though they may have a positive impact on the local economy

- Given the challenges, semi-HSR (trains at up to 200 km per hour) will more likely be focused on initially

The Diamond Quadrilateral HSR projects

What Is HSR?

- It refers to trains that run at 300 km per hr or more

- Fencing is mandatory; and new tracks have to be laid

- Low probability of projects being completed by 2019

- First project may be Mumbai-Ahmedabad HSR, estimated to cost Rs 90,000 crore

- Modi’s vision is to have a 10,000 km HSR network

Other High-Speed Train Corridors

- 991 km Delhi-Agra-Lucknow-Varanasi-Patna, Pre-feasibility study done

- 135 km Howrah–Haldia Pre-feasibility study done

- 664 km Hyderabad-Dornakal-Vijayawada- Chennai, Study in progress

- 850 km Chennai-Bangalore-Coimbatore-Ernakulam-Thiruvananthapuram Draft final report submitted

- 450 km Delhi-Chandigarh-Amritsar Feasibility study done by French

- 591 km Delhi-Jaipur-Ajmer-Jodhpur Study still to be started

Global Speed Monsters’ Parade

First the bad news: very few high-speed trains are profitable. And the positive: a significant trickledown effect on the entire economy.

- 10 million

Eurostar: High-end and high-speed with no or few stops, like Eurostar and Thalys, which cater to 10 million passengers a year

- 40 million

European model: Largely French, and basically inter-city; have some mid-fare options; carry 30-40 mn passengers a year

- 60 million

Asian model: Cater to populated areas with 60 million (South Korea) and 100 million (Japan) passengers. Affordable fares.

The Lessons

- Barring Tokyo-Osaka and Paris-Lyon, most bullet train routes run on losses and are subsidised.

- Eurostar is among the few profitable bullet train systems operational currently.

- Tariff depends on volumes—lower the volume, higher the tariff. The trend is to keep tariff lower than air fare.

By Lola Nayar with Pritam Sengupta in Beijing