It will be 12 years on September 28. A long time for justice. Abdul Sharif, an auto driver from Bandra (East), had lost his elder brother Nurullah Mehbub Sharif in an accident. That day in 2002, about 2:45 am in the morning, actor Salman Khan allegedly drove his SUV on to the pavement and into the facade of the American Express Bakery on Hill Road in Bandra (West). The Toyota Land Cruiser had, as per the prosecution case, run over five persons sleeping on the pavement. Four survived with injuries. The fifth, Nurullah, died.

Twelve years on, even the Rs 10 lakh compensation eludes the claimants: Nurullah’s brother and a son from his divorced wife. The Bombay High Court, which had ordered Salman to deposit Rs 19 lakh in compensation, has demanded proof of identity and they have been unable to satisfy the court. (Meanwhile, the four injured have shared their compensation of Rs 9 lakh.)

But there has been no verdict in the case itself, being tried in a sessions court. Khan pleaded not guilty and the trial has been going through several twists and turns. The court was told Salman had fled the spot and tests showed he had been under the influence of alcohol. Two witnesses in the case—Salman’s police guard, who was riding in the SUV, and one of those run over—had changed their statements during the course of the trial. Initially charged with negligent driving (maximum punishment: two years’ imprisonment), he now faces the charge of culpable homicide not amounting to murder (maximum charge: 10 years’ imprisonment).

The police has been accused of being soft in prosecuting the actor. Activists raised questions over Salman dancing at a Mumbai police function in 2012. Wasn’t the connection inappropriate? Earlier this year, the police had actually told the court the case files had all gone missing. Mysteriously, they have reappeared and the trial is set to continue. Salman had alleged he was being subjected to a parallel trial by media. He even set up a website (salmankhanfiles.com) to furnish information on the case. “Prosecution,” his lawyer said, “should not turn into persecution.”

There’s a long haul ahead. Since the charge itself has been upgraded to a more severe one, the odds stacked against getting a favourable verdict would have proportionately risen too. And if the sessions court holds him guilty, he is bound to appeal to the high court. If it acquits him, the prosecution may well fold up its case too.

Why is this case so special? In most hit-and-run cases, drivers are never caught. Those apprehended are charged with negligent driving and get away with it, even if they were drunk at the wheel. Cases do not drag on for so long. Alistair Pereira, who mowed down seven pavement-dwellers in November 2006, was sentenced within a year after an appeal to the high court. Noorie Haveliwala, who ran over two persons in 2010, was sentenced in 2012. Salman’s case has been comparable in duration to hot potato political corruption cases or those of commissions inquiring into riots and getting one extension after another.

Nurullah’s brother Abdul recalls that, to claim compensation, their mother Fatima filed an appeal in 2002 that she was his legal heir. Nurullah’s ex-wife, who has since remarried, also filed an appeal in the name of her son from him, Firoz. “Despite offers to split the amount, his ex-wife refused,” he says. “My mother died last year without seeing a paisa of the compensation.” Firoz, who is 27 now, lives in penury in Uttar Pradesh. And Abdul drives an autorickshaw in Mumbai, but cannot earn enough to keep his wife and three children in the big city. Off and on, he takes off to his in-laws’ village in Aurangabad district to help them in their wood business. Pretty much like everyone else, his responses dry up too when asked about Salman.

Shrikant Shivade, who now defends Salman after other lawyers before him, says, “I hope the documents going missing doesn’t affect the case. I don’t know why they were not submitted in court in the first place. Nowhere else does the police keep original documents with them once a case is in court.” On his case website, Salman says he’s afraid the absence of original case papers might cause prejudice against him.

In an intervention application filed by Santosh Daundkar, lawyer-activist Abha Singh has highlighted the role of the police in the delay of the trial. “We were told by the court that our application will be heard only after the trial is concluded. We are focusing on the issue of (submission of) false evidence by the police, which has caused interminable delay in the case,” she says, speaking about the other cases such as the Lavasa and Adarsh scam, in which she and her husband Y.P. Singh have moved intervention petitions.

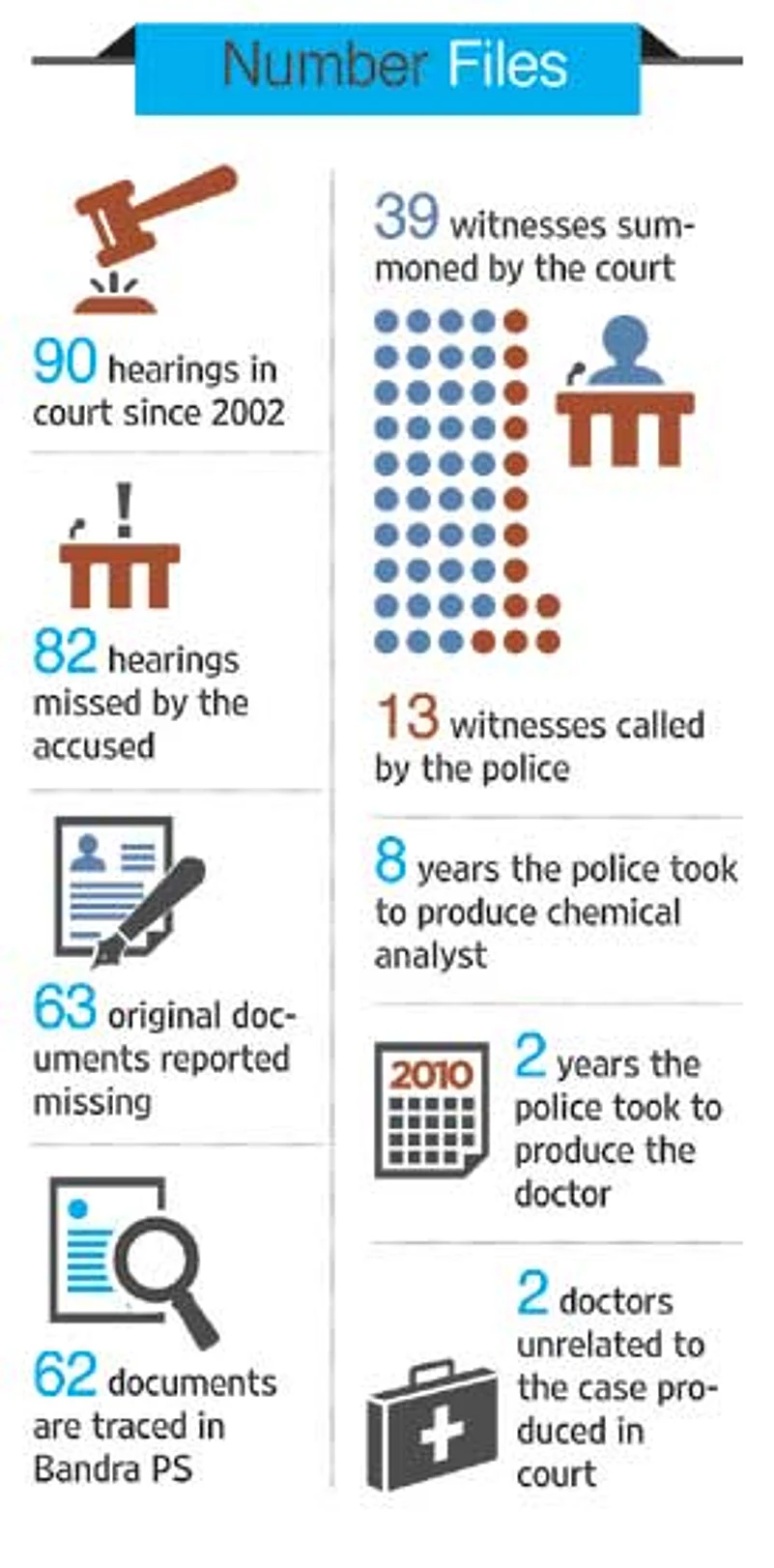

In the application, with the help of documents procured under the RTI, which they made public in 2012, they have detailed how the police failed to summon crucial witnesses, produced witnesses who were not examined by the prosecution or indeed produced the wrong witnesses. “Thus, out of the nine witnesses the Bandra police was required to produce before the court on March 23, 2006, they produced only one,” says her note. (Despite repeated requests, the police commissioner was not available for comment.)

The trial has already been arduously long: there have been more than 90 hearings at various levels of the judiciary—the metropolitan magistrates’ court, sessions court, the high court and the Supreme Court. Much time was spent deciding if Salman needed to be tried for rash and negligent driving or for culpable homicide not amounting to murder.

After the accident, veteran journalist Nikhil Wagle had filed a public interest legislation. Says his lawyer Nitin Pradhan, “Sec 304 A of the Indian Penal Code was enacted in 1917, when the fastest vehicle on road was a horse-carriage. One must study sentencing policy as an indicator of how the legislature treats offences. Serious offences get longer punishment. Today, mean machines such as SUVs are common on the streets, and in a second they accelerate from zero to 60 kmph.”

Photograph by Apoorva Salkade

The petition discusses several issues, including the character of the actor based on previous run-INS with the law and rumoured reports in the press about the accident. It discusses the need to change the law and bring in stringent sections for causing death through negligent and/or drunken driving. The petition also makes a case for the accused to deposit a compensation for victims based on his social status. Says Pradhan, “We made the case that if you drink and take the wheel, you know that in case of an accident, it is likely to be fatal. Hence, the need for stricter charges and longer punishment.”

A prime witness in the case, constable Ravindra Patil, who was assigned to provide security to the actor, and who had given conflicting statements saying first that the actor was inebriated and was advised not to take the wheel and then that he himself was driving the vehicle, went missing. He was arrested in March 2006 and discharged from the police force for absence from duty in November 2006 and died at the Sewri hospital for TB in 2007.

In the note prepared by Singh, she raises questions on whether Salman Khan’s bail should have been cancelled on the disappearance of Patil. It says: “...a police constable—the star witness of this case, appeared and then disappeared and then appeared again and later disappeared till he was arrested on a non-bailable warrant issued by the court. It is most surprising to note that, despite such a massive manipulation of witnesses, no application was moved by the police to cancel the bail of Salman.” However, legal experts say no one can be blamed because it was a combination of factors. “It is a tiring judicial process that includes the accused’s right to challenge orders at various levels,” says Pradhan. Referring to the back and forth that happened on framing of charges, he says, “Now this is a judicial process, one can’t blame the police or the judiciary or the accused. And the accused is merely taking advantage of procedural rights. However, the delay in disbursing the amount due to internal fights is astonishing.”

Lawyer Javed Hussain, who represented the victim’s mother and the brother, says, “It is so heart-wrenching that the mother not only lost her son, but never even saw any compensation amount.” Abdul says there will be some solace if the case ends in a conviction. “Rooh ko thoda aaram milega.”

Ibrahim Mulla, a lawyer representing Abdul and the son of the deceased in a succession petition, as required by the high court, says, “If there had been a conviction (before her death), the mother could have at least felt that some justice was done.” He says it could take another year or two, but the stamp duty alone will cost Rs 50,000, and neither family can afford it. In those 12 years, Salman has kicked up a Rs 300-crore storm at the box-office. He has another release lined up next year. Meanwhile, the Khans have been cosying up to PM Narendra Modi, with Salman seen in photo-ops when Modi was Gujarat CM.

The Trial, Kafka’s novel of oppressive bureaucracy and the hunt for justice, can be read in a few months. In India, reality is far worse than that fiction. Nurullah’s indigent, ill-educated family wouldn’t know that even though they are experiencing it.

***

Twists & Turns Of The Trial

- Sep 28, 2002 Salman’s Land Cruiser rams into a Bandra bakery, killing one and injuring four others sleeping on the pavement.

- Oct, 2002 Bombay High Court, hearing a PIL, orders the actor to pay a compensation of Rs 19 lakh

Initial reports The actor was drunk, could not walk straight and was driving the vehicle. Reports held he fled from the spot. - 2006 Trial began before Metropolitan Magistrate, Bandra. Actor charged with rash and negligent driving carrying a punishment of two years’ imprisonment. Witnesses turned hostile. The police bodyguard Ravindra Patil, who was riding with Salman, claimed he was at the wheel.

- 2007 Patil, suspended from the police force, is reported dead.

- 2010 Chemical analyst who tested the blood sample deposes that the actor had 62 mg of alcohol in his blood.

- 2002-13 Police accused of negligence, of protecting the actor and of delaying the trial through various means.

- Dec 2012 Magistrate’s court orders a fresh trial for culpable homicide not amounting to murder carrying punishment of 10 years’ imprisonment.

- Jun 2013 Sessions court rejects actor’s appeal against order for fresh trial.

- Sep 2013 Court rejects intervention petition filed by activist Abha Singh

- May 2014 Francis Fernandes, a neighbour of the actor, tells court that he was an eyewitness and that the actor did not smell of alcohol

- Jul 2014 Court informed that 63 original statements and case diaries missing

- Aug 2014 Court informed that documents not traceable

- Sep 2014 Court informed that 62 of the 63 original statements etc found in Bandra Police Station

- Sep 24, 2014 Trial set to resume

By Prachi Pinglay-Plumber in Mumbai. A version of this appears in print