The delayed launch of the Women’s Premier League, 16 years after the men’s IPL despite both being run by the BCCI, reflects long-standing and systemic gender inequality in Indian cricket.

Former women cricketers from Jharkhand recount generations of neglect, where playing the sport meant enduring poor travel and accommodation.

Even today, disparities persist at the grassroots level, with Jharkhand having extensive infrastructure for men’s cricket but minimal facilities and academies for women

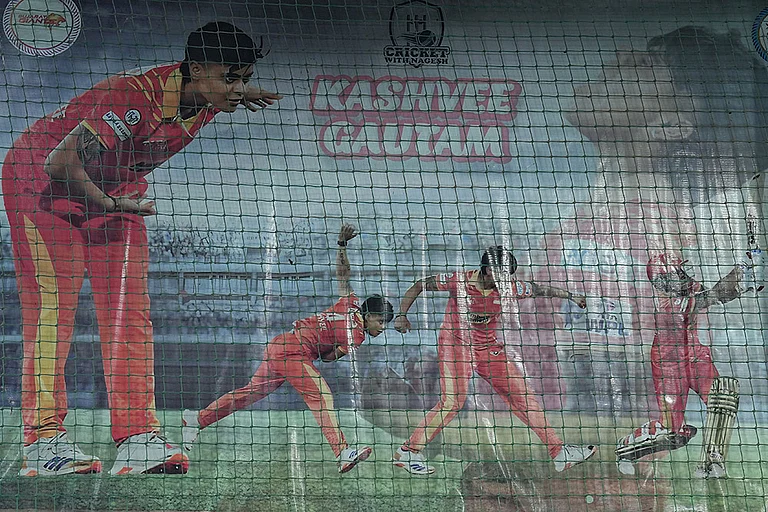

One Battle After Another: Jharkhand's Failing Infrastructure For Women's Cricket

Women’s cricket in Jharkhand is not built on infrastructure, funding or institutional care. It has survived on endurance and sacrifice

“Even after playing the World Cup, we didn’t get a single rupee as match fee.”

“We spent many nights in extreme cold, sleeping on a thin mat on the floor.”

“We travelled to tournaments sitting near the stinking toilets in the general compartment.”

“We were forced to defecate in the open.”

These are not isolated complaints or exaggerated memories. They are the words of former women cricketers from Jharkhand, spoken across generations, describing a sporting life shaped by deprivation and neglect. Gender discrimination, they insist, existed earlier and continues even today. Across Indian sport, inequality takes many forms, but in cricket, its shadow has been longer and more entrenched. Each time men enter a new professional space or format, women seem to arrive years, sometimes decades, later.

The disparity is visible even at the highest level. The men’s Indian Premier League began in 2008. The Women’s Premier League was launched only in 2023. Both tournaments are run by the same cricket board, the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI), now the world’s richest sport’s governing body. Yet women entered this marquee league 16 years after men, despite equality in sport having long entered public discourse.

Before women’s cricket came under the BCCI in 2006, it was governed by the Women’s Cricket Association of India. In states where men’s cricket itself struggled for attention, women’s cricket survived with little visibility or support. Jharkhand was one such state. For its women cricketers, reaching national and international levels was not merely about performance, but about enduring conditions that routinely stripped the game of dignity.

Travel often meant unreserved journeys in general compartments, hours spent standing or sitting near train toilets. Accommodation, when arranged, could be a single room in a school or dormitory, with thin mats on the floor and no bathrooms. Food was uncertain. There were no grants, no allowances and no match fees. Playing the game frequently meant paying from one’s own pocket.

Jay Kumar Sinha, associated with women’s cricket in undivided Bihar since 1979, recalls one such journey vividly. In 1982-83, the Ranchi University women’s team travelled to Jaipur for a university tournament. The entire team travelled seated near the toilets in the general compartment. They returned as champions. The struggle, he says, has never fully ended. Even today, Jharkhand’s districts lack basic facilities for women’s cricket. Ranchi has 18 academies for men and none for women. Across 24 districts, there are barely one or two academies, except in Jamshedpur.

For Seema Singh, these hardships defined an entire career. Now 46, she began playing cricket in class six and entered domestic cricket in 1990, when women’s cricket in undivided Bihar was largely confined to Jamshedpur. She went on to play nearly 200 domestic matches and represented India A against Australia in 2004. Yet her memories of the sport are shaped as much by travel and survival as by cricket.

“It was a very difficult phase. In 1996-97, Bihar’s junior team went to Lucknow for the Junior Nationals and I was part of that team. We travelled without reservations in the general compartment. Many of us had to sit near the toilet and reach Lucknow like that,” she recalls.

On another occasion, during a state-level match in Hajipur, the team slept on thin mats in a government school in bitter cold, using blankets brought from home. Many tours, she says, offered no bathroom facilities at all. “We were forced to defecate in the open.”

Seema’s continuation in cricket owed little to institutional support. An Indian Railways job secured through the sports quota in 1995 made it possible for her to keep playing and eventually to represent India. Today, she coaches the Jharkhand women’s team.

Kavita Roy’s journey follows a similar path. From Hajipur, she moved to Jamshedpur as a teenager to pursue cricket, playing across age groups for Bihar and later Jharkhand. In 2000, she represented India at the World Cup in New Zealand. The team received no match fee and no daily allowance. Travel to and from the tournament was arranged, nothing more.

“Men and women played the same game, but the difference was like the sky and the earth,” she says. “Men were paid, but we had to spend our own money to play. Still, we were happy because we were passionate about cricket.”

If this was the condition at an international tournament, she says, domestic cricket was far worse. Stability came only after she secured an Indian Railways job in 1997. Without it, she believes, she too might have left the sport, like many others who simply could not afford to continue. She recalls several talented players quitting because cricket offered no income and no security.

Her own entry into the sport was shaped by resistance. In a conservative social setting, she played with boys, closely accompanied by her parents. She was spotted during a match in Hajipur by coach Tarun Kumar Bose, who brought her to Jamshedpur for serious training. Kavita went on to play seven international matches and over 250 domestic matches before retiring in 2019.

For an earlier generation, the price of staying in the game was even higher. Charanjit Kaur began playing in Jamshedpur in the mid-1970s, when women’s cricket had barely taken root. She played over 200 domestic matches and an international against England in 1982. During the WCAI era, there was no payment at any level. Players paid their own expenses. Coaches raised money by seeking help. Sometimes teams could not even travel for tournaments.

“How long could we keep paying from our own pockets?” she asks. With no support, she eventually had to leave the game. Her father’s government job had allowed her to play longer than most, but even that had limits. The merger with the BCCI in 2006, she says, did not bring immediate relief. Domestic match fees remained as low as Rs 1,000 for years.

For Shubhlakshmi, who entered domestic cricket just before the merger, the changes were visible but limited. Even while playing for India between 2012 and 2015, payments were made as lump sums for entire tours, not match by match. Men, by then, earned lakhs per match and held contracts worth crores. Women’s contracts arrived only in 2016-17.

A fast bowler with 29 international matches and more than 200 domestic appearances, she too relied on an Indian Railways job to sustain her career. Social pressure followed her early years, with relatives questioning the value of a girl playing cricket. Her parents shielded her from these taunts. Today, she notes, the same society drops daughters off at grounds to play sports.

Veterans like Shashwati Mukherjee and G.S. Lakshmi recall an era with no proper grounds and minimal equipment, when an entire team shared a single bat. Losing a match meant returning immediately because there was no provision for food or accommodation. Nights were spent on mats in halls and dormitories. Lakshmi retired the same year women’s cricket came under the BCCI, missing even the limited improvements that followed. Her pride lies elsewhere, in becoming the world’s first female ICC match referee.

Taken together, these testimonies tell a consistent and uncomfortable truth. Women’s cricket in Jharkhand was not built on infrastructure, funding or institutional care. It survived on endurance and sacrifice. Even after coming under the BCCI, inequality did not disappear. Payments remained lower, facilities fewer and recognition delayed.

This is not only a story about sport. It is about what happens when talent is left to struggle in silence, when women are made to fight merely to be seen and taken seriously. For decades, these players kept going, not because the system supported them, but because they refused to stop.

Md Asghar Khan is senior correspondent from Jharkhand

Tags