The SC found that the regulations “were prima facie vague and easy to misuse”.

The writes notes that upwardly mobile, neo-rich, affluent, educated OBCs (and Dalits) across religious divides have turned Rightward in terms of competitive identity-politics.

Mainstream media debates have long before given up on informed debates, providing spaces to all shades of opinions, and have taken recourse to cacophony.

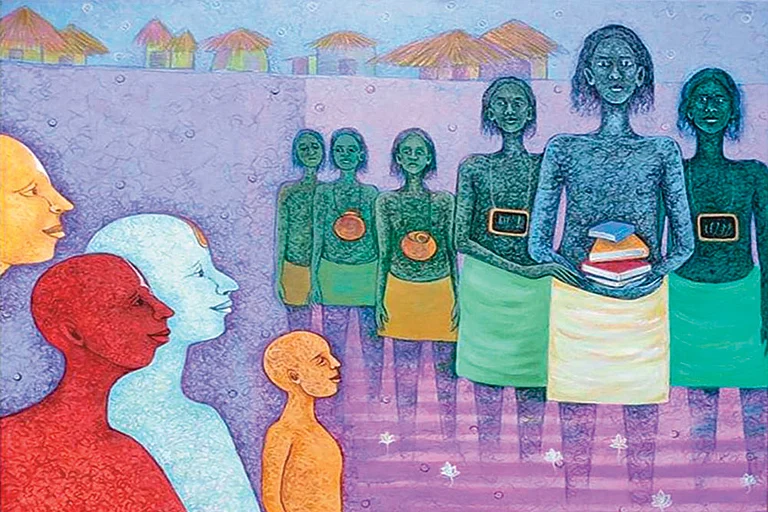

Everybody Is A Guerrilla: No Justification For Opposing The UGC Equity Regulations

The Supreme Court of India hastily put a stay on the latest gazette notification of the University Grants Commission’s (UGC) Equity norms.

“When everybody wants to fight there is nothing to fight for. Everybody wants to fight his own little war, everybody is guerilla. ...Those who have won will win every war,” said the Nobel Prize-winning novelist, Sir V. S. Naipaul (1932-2018) in his 1975 novel, Guerrillas.

That is where the latest eruption of Indian campus youth in upper caste locations eventually culminated into. The historically victorious and dominant castes-classes came out victorious once again. The Supreme Court of India hastily put a stay on the latest gazette notification of the University Grants Commission’s (UGC) Promotion of Equity in Higher Education Institutions Regulations, 2026, gazetted on January 13, 2026, which mandated stringent measures to eradicate discrimination based on caste, creed, religion, language, gender, or disability in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs).

Solicitor General Tushar Mehta, appearing for the UGC and the Union of India, had made no arguments against the petitioner’s submissions—testifying a tacit support from the government to the petitioners!

What was there in the impugned regulations provoking the upper castes and forcing them on to the streets? A quick look into the key aspects of the regulations suggests its objective is to eradicate discrimination and promote equity and to ensure a non-discriminatory campus environment. Regulations, technically speaking, are delegated legislations, which means laws already exist. Only the ways of enforcement have been worked out through the regulations. Thus, as the pre-existing laws haven’t been opposed, there is no justification whatsoever for opposing these regulations.

It defines discrimination as any unfair, biased, or differential treatment (direct or indirect) that violates human dignity or equality. It underlines the institutional duties to ensure no discrimination occurs in admission, evaluation, or campus life. It makes it mandatory to set up Equal Opportunity Centres (EOCs) to handle complaints and to monitor compliance. It also asks the educational institutions to establish Equity Committees chaired by the Head of the Institution, with representation from the marginalised groups—Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), Other Backward Classes (OBCs), women and disabled/differently-abled. Complaints require action within 24 hours and investigations must be completed within a fortnight; and, annual reporting of equity measures to the UGC is mandatory.

Apparently, one hardly sees anything wrong in these provisions. The massive protests therefore left us intrigued. The protesters have hardly been able to articulate their comprehensive critique of these “equity regulations”. My students from upper caste backgrounds too failed to articulate, though, my own campus—Aligarh Muslim University—arguably for its demographic composition—appeared to be indifferent to the regulations, just as it remained silent in 1990 when anti-Mandal followed by pro-Mandal protests had happened.

After much probing, I could gather an impression that their grievance is about the apprehensions of misuse of the regulations. The Supreme Court too, in its own wisdom, granting a stay—on January 29, 2026—found that the regulations “were prima facie vague and easy to misuse”. The central concern is clause 3 (C) which defines “caste-based discrimination” by excluding the historically privileged upper castes.

The Supreme Court too, in its own wisdom, granting a stay—on January 29, 2026—found that the regulations “were prima facie vague and easy to misuse”.

It suddenly occurred to me that we keep coming across instances of misuse of dowry laws, laws to penalise offences against the SCs, STs and gender justice laws—for which Internal Complaints Committees (ICCs) exist on university campuses. Yet, these laws haven’t been asked by such forces to be repealed, as yet.

We are also witness to the intolerable facts of hoodwinking such laws, more specifically in some of the cases of gender harassment—even permanently employed professor-victims end up giving up the fight for various societal reasons while the aggressor-professors get no punishment from the university, even after being convicted by the ICC. In certain cases, even the women heads (vice chancellors) of the institutions turn out to be unhelpful to the aggrieved women. Patriarchy, just like the caste-based powers and privileges, is so strong and entrenched.

My memories went back to my undergraduate days in 1990. Protesting against the partial implementation of the Mandal Commission Report (after a decade of its submission, in 1980), upper caste students and youth had turned themselves into riotous mobs vandalising and ransacking public properties. Then, some constituents of the coalition in power showed their tenacity. There was no rollback, despite massive protests. Judicial review too couldn’t do the rollback. North Indian provinces (the Hindi Belt) were ruled by post-Congress regimes (most of them subsequently turned into regional outfits). Their leaders, the OBC chief ministers (along with their Dalit leaders) too came out on the streets counter-mobilising their own support base against the anti-Mandal protesters.

This time, in 2026, we couldn’t see such kind of political counter-mobilisation to keep the equity regulation intact. This contrasting political fallout needs to be looked into. In the decades prior to the Mandal era, Bihar had implemented the Mungeri Lal Commission report in 1978. This in itself was preceded and followed by incidents of caste wars on the campuses. The partial successes of the half-hearted implementation of the land reforms, the coming of the Green Revolution, and the overall growing strength of democracy had resulted in the creation of middle classes among the new rural elite (intermediate castes, now called as the OBCs, led mainly by the Yadavas, Koeris, Kurmis and Jats), besides the emergence of the affluent segments of the Dalits.

These new rural classes (Kulaks or the “Bullock Cart Capitalists”, to borrow the expression from Susanne Rudolph and Lloyd Rudolph’s 1987 book, In Pursuit of Lakshmi) had staked their claims of shares in the structures and processes of power, more specifically in the urban spaces offering higher education. These “Demand Groups” were now marching towards becoming “Command Groups”. Thus, the university towns were specifically witnesses of frequent group clashes, not to mention the agrarian struggles characterised by the assertion of the poor landless peasants against the landlords. Such group conflicts emanated at times from ragging, at times around hostel allotments, and at times, around other trivial issues. P. N. Gour’s 1984 book, Student Unrest in the University of Bihar, 1967-72, tells us “Casteism” is rightly considered as the bane of social, cultural and political life in Bihar and the supervening cause of its persistent backwardness. Because this primitive feeling of not belonging to your society, state or country as a whole, but only to your caste or clan, has not only stood in the way of Bihar’s present social cohesion, economic prosperity and political stability, but also bodes ill for her future on account of its vitiating influence on the younger generation receiving higher education in her universities. Similar explorations have been made by Craig Jeffrey about the Jats of Meerut University and by Philip Altbach about student politics all across the world. Political scientist Atul Kohli characterised such assertions as a “revolution of rising expectations”.

Long before entering into the second quarter of the 21st century, in the era of institutional meltdown all across, we have already become familiar with expressions such as “end of ideologies”, “post-truth”, media “manufacturing consent” in favour of corporate-controlled regimes. We are now becoming normalised with political parties and state institutions dancing to the tunes of a handful of big capitalist-industrial houses, and mediatised anti-minority hatred and violence that can hypnotise a huge majority of the population to harbour the illusions of “all is well”, to keep the ever-growing socio-economic inequalities quite off their view.

Even feeble and under-articulated protest has been considered to be strong enough to push the state back, and clinched the success of rollback.

By the time we entered 2026, quite a significant segment of the upwardly mobile, neo-rich, affluent, educated OBCs (and Dalits) across religious divides have turned Rightward in terms of competitive identity-politics, in their demonstrative religiosity and politics of piety; consumerist culture taking over religious rituals and spectacular ceremonies; and, fiercely vengeful public display of such religiosities to announce their arrival in terms of education, economy, and political assertion. This has given a menacing rise to competitive identity politics, and has by now discredited the expressions of Constitutionalised aspirations such as socialism and secularism.

University campuses are falling prey to all these socio-economic and political developments. In such an era, while the privileged castes appear to be successfully pushing back the state and its half-hearted measures of enforcing equity, avenues of judicial review too appear to be coming to their rescue. Even feeble and under-articulated protest has been considered to be strong enough to push the state back, and clinched the success of rollback. Mainstream media debates have long before given up on informed debates, providing spaces to all shades of opinions, and have taken recourse to atrocious cacophony, hounding and silencing the voices of dissent. Marginalised segments have to take recourse to the alternative media, which again is marginalised.

Historically disadvantaged or marginalised segments thus appear to have taken “sleeping pills” (or the pills of anti-minority communal hatred). Ironically, it is the upwardly mobile OBC-Dalit Hindus who have been targeting their counterparts among the Muslims, apparently to avenge the real and imagined victimisation inflicted upon these Hindus centuries ago by the ethnically different Medieval Muslim rulers. The state-run bulldozers or the disenfranchisement of the hapless Muslims (mostly belonging to their corresponding castes/classes) give them such a glee, compensating, so to say, their miseries and helplessness against the instances of rollback of the laws for equity and socio-economic justice.

Even this diagnosis is contestable, given my own location-identity. I work and live in the Muslim-majority campus of Aligarh Muslim University. Recently, the self-admitted fact of a massive fee scam in the university failed to rouse the campus and the Qaum (community) which otherwise keeps itself seeped into the narratives of victimhood. Not a single religio-cultural and political (including the political parties) organisation of India’s Muslim communities came out to speak against this massive fee scam (in which some teacher-administrators too have been found to be gross defaulters in paying fees for their children enrolled under the non-resident Indian-NRI quota) and against many other irregularities pertaining to examinations, enrolments and recruitments, not to speak of the corruption-prone issues of construction and supplies, and outrageously long continuation of a select few teachers in almost the entire administration of the university.

Did the columnists and narrative-making elite of Muslims speak out against these ills afflicting the Muslim-dominated public institutions of education, such as the massively funded Aligarh Muslim University? They are busy fighting what they call Hindutva majoritarianism and “fascism”. Strangely enough, they have chosen not to wage fights where Muslim stakes are considerable, and where wrongdoers too are Muslims, and therefore, prospects of Hindutva repression may possibly be negligible (for the obvious reason of treating it as an “intra-Muslim” affair). Are they so naïve that they can’t see these misplaced priorities? Or, are they supremely cunning in how they preserve their class interests even while administering (dis)proportionately heavy doses of the opium of victimhood narratives? [It must, however, be added here by way of giving even the proverbial devil its due that the supposedly Hindutva-dominated state bureaucracy of audit and the Union ministry of education displayed a semblance of intervening into it more swiftly, for corrective steps, even while the Qaum’s own narrative-making elite went silent to keep themselves benefitted from such scams and irregularities.]

While the historically privileged groups (upper castes and classes) are able to wage a feeble or sham resistance to safeguard their retrogressive and unjustifiable privileges, the marginalised ones have got their priorities defined in strange ways. The elite and neo-elite among the marginalised social groups/identities in and beyond the campuses are embedded with—or co-opted by—the privileged groups. Self-centric and parasitic elites of the marginalised segments, including the Muslim minority, are yet to be exposed adequately.

That’s how we are reminded of Naipaul’s creative remark with which this essay began: “When everybody wants to fight there is nothing to fight for. Everybody wants to fight his own little war, everybody is guerilla. ...Those who have won will win every war.”

(Views expressed are personal)

Mohammad Sajjad is a professor of Modern And Contemporary Indian History at Aligarh Muslim University

This article appeared in Outlook's February 21 issue titled Seeking Equity which brought together ground reports, analysis and commentary to examine UGC’s recent equity rules and the claims of misuse raised by privileged groups.

Tags