Communist leader A. K. Gopalan became one of the first people on whom the Preventive Detention Act, 1950 was used

The PDA was repealed in 1969, but the DIR, UAPA and MISA soon followed.

Almost all political parties that have been in power in states have used these laws, especially the UAPA

A Legacy Of Detention: Weaponisation Of PDA, TADA, NSA And UAPA Laws Since Independence

Since Independence, a number of laws have been enacted that allow preventive detention which have been widely used by all regimes against their political opponents

Preventive detention, a colonial era practice to crush political protests, smoothly found its way into post-colonial India, among many other legal frameworks limiting personal liberty. Climate activist Sonam Wangchuk, one of its victims, may well blame Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar for his confinement.

In September 2025, Wangchuk, the Ladakh-based activist, was detained under the National Security Act (NSA), 1980, after protests broke out in Ladakh against several policies of the Union government. His confinement continues as we enter the third week of January 2026.

The NSA allows putting someone under preventive detention. It draws its Constitutional validity from Article 22 of the Indian Constitution. Three quarter of a century ago, on September 15, 1949, Constituent Assembly member Mahavir Tyagi had warned Ambedkar, who was chairman of the Constitution Drafting Committee, that the Article which the drafting committee was introducing would “enable the future Governments to detain people and deprive them of their liberty rather than guarantee it”.

September 15, 1949, was a day of heated arguments in the Constituent Assembly. Tyagi, a Congress leader, expressed his “fond wish” that Ambedkar and other members of the Drafting Committee “had had the experience of detention in jails”. Ambedkar responded by saying, “I shall try hereafter to acquire that experience.” To this, Tyagi assured Ambedkar that although the British Government never detained him, “the Constitution he is making with his own hands will give him that privilege in his lifetime.”

Questioning the relevance of a preventive detention clause in the Constitution, which is meant to guarantee fundamental rights to the citizens, Tyagi argued that he feared the introduction of such a clause would “change the chapter of fundamental rights into a penal code worse than the Defence of India (DoI) Rules of the British government”.

Just a few days before this, Article 15 (now Article 21) had gone through a modification that triggered widespread criticism. The Article originally read: “No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty without due process of law.” However, the phrase “due process of law” was replaced with “procedure established by law”—which was construed as giving too much power to the party in government, as they could regularise every detention simply by bringing in laws the way they deemed fit.

This new article, 15A (which subsequently became Article 22) was formally brought in as “compensation” for the changes. It ended up making Constitutional provisions for preventive detention, as it debarred those “arrested or detained under any law providing for preventive detention” from enjoying some of the guaranteed rights. Besides, it rather loosely worded the duties of the authorities and the rights of the detainees.

Tyagi alleged that the Article (15A-turned-22) will likely be used freely by future governments against its political opponents. “As soon as another political party comes to power, he (Ambedkar) along with his colleagues will become the victims of the provisions now being made by him,” he cautioned.

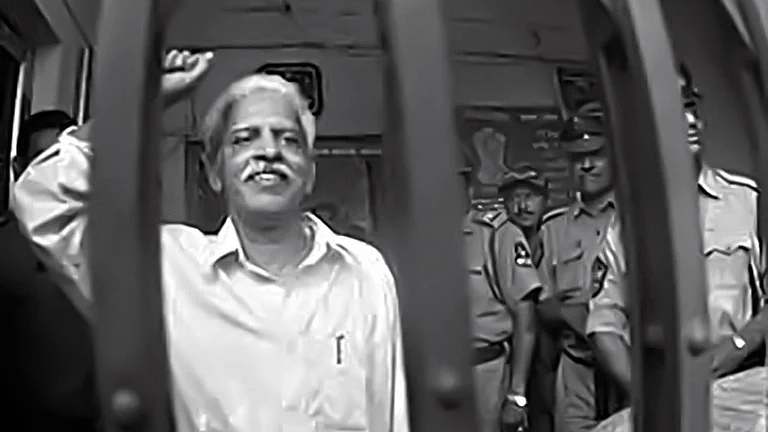

Despite such opposition, the Article became a reality in India’s Constitution. The Preventive Detention Act, 1950, (PDA), was enacted soon after. It enabled indefinite detention without disclosing grounds or evidence. Communist leader A. K. Gopalan became one of those it was first used upon. He challenged the PDA.

However, the top court ruled what was already anticipated—Article 21 provides for “procedure established by law” and the PDA is a law enacted by Parliament and it has its own procedures. Besides, Article 22 sets up guidelines for preventive detention, effectively validating the foundation of having preventive detention laws.

Since then, scores of activists, opposition leaders, dissenters and separatists have faced forced confinement within jail cells for challenging—or even questioning—power. There also existed the colonial-legacy-carrying Public Safety Act in different states, for example, Madras and West Bengal.

During the 1960s, socialist leader Ram Manohar Lohia was arrested multiple times under laws based on preventive detention and public order for his anti-Congress activism. In southern India, the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) leaders were arrested during anti-Hindi agitations of 1965.

The PDA was repealed in 1969, but the government already had another law for detention—Defence of India Rules (DIR), 1962, which enabled indefinite detention without trial. The Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, or the UAPA, also came into being in 1967. By 1971, India had a more stringent law, the infamous Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA), 1971, which allowed preventive detention without warrants and up to two years without trial.

Activists, opposition leaders AND dissenters have faced confinement within jail cells for challenging—or even questioning—power.

Meanwhile, amidst government high-handedness in contouring the Naxalite armed rebellion, India saw the birth of a series of human rights organisations—Association for Protection of Democratic Rights (APDR) in Kolkata in June 1972, the Andhra Pradesh Civil Liberties Committee (APCLC) in 1974, Organisation for Protection of Democratic Rights (OPDR) in 1975, the Committee for Protection of Democratic Rights (CPDR) in Maharashtra in 1977, and the Association for Democratic Rights in Punjab (AFDR) in 1978. In 1976, Jayaprakash Narayan launched the People’s Union for Civil Liberties and Democratic Rights (PUCLDR), which split in 1980 to become PUCL and PUDR.

The thousands of political opponents and Naxalite activists arrested during Emergency (1975-77) were mostly released after the 1977 election that decimated the Congress. Even though there was no category defined as political prisoners, the newly-elected Left Front government in West Bengal issued a policy guideline the same year, declaring a general amnesty to all political prisoners. Eventually, they were released.

Despite such an atmosphere, new laws kept coming. The NSA came in 1980. It permitted up to 12 months detention without trial for security threats. Five years later, the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act (TADA), 1985, was enacted. It allowed confessions to police to be considered as evidence and made obtaining bail really difficult.

After TADA lapsed in 1995 following widespread criticism for its abuse, another law was enacted—the Prevention of Terrorism Act (POTA), 2002, which too, faced the charge of rampant abuse. After the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government came to power removing Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government, POTA was repealed in 2004. However, the UAPA of 1967 was simultaneously amended and strengthened to make up for the loss of POTA.

The UAPA Amendment Act, 2004, significantly expanded its scope by formally introducing the definition of “terrorist act” and related offences. The UAPA was further strengthened with the subsequent amendments—the 2008 and 2012 amendments brought in by the Manmohan Singh-led UPA government and the 2019 amendment implemented by the BJP’s Narendra Modi-led NDA government.

A common trend during the past 3-4 decades is that opponents in electoral politics are usually jailed in connection with cases involving corruption or money laundering, whereas political activists associated with essentially non-electoral mass movements face charges under special laws, including anti-terror and sedition laws.

In 1996, after the then DMK chief M. Karunanidhi came to power, his government had jailed former chief minister J. Jayalalithaa of All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) on corruption charges. In 2001, after Jayalalithaa returned to power, she took revenge by getting the police to drag the 77-year-old Karunanidhi out of home in a midnight raid in connection with a corruption case.

In a 1988 essay, human rights activist K. Balagopal had drawn the distinction quite carefully—one group of political activists opposes merely the ruling family or the ruling party, while the other group opposes the State. It is for the latter that laws concerning terror and sedition and allowing prolonged incarceration without trial are chiefly used. From Assam’s anti-dam activist Akhil Gogoi and Jharkhand’s priest-cum-human rights defender Stan Swamy to Delhi’s anti-communalism activist Umar Khalid, the list is long.

Balagopal pointed out that the second category of people—who were effectively being treated as political prisoners without any formal recognition—suffer from a prison regime “much more undemocratic than the non-political undertrials suffer”.

“They can be, and are, being treated as a different category of prisoners to whom even the minimum rights available to ordinary undertrials are not available,” he wrote.

Almost all political parties that have been in power in states have used these laws, especially the UAPA, including the Left government in West Bengal and Kerala, and Mamata Banerjee’s Trinamool Congress government in West Bengal.

In the Indian history of the post-colonial period, there was only one example of a government formally recognising a category of jail inmates as “political prisoners”, who were entitled to some benefits like the supply of newspapers and reading and writing materials. It was the West Bengal Correctional Services Act of 1992 passed by the Jyoti Basu-led Left-front government.

Its Section 24 said, “Any person arrested or convicted on a charge of having committed or attempting to commit aiding or abetting the commissions of any political offence, whether or not the act constituting such offence comes within the preview of any offence punishable under the Indian Penal Code or any other law for the time being in force, or any person believed to have been prosecuted out of political animosity or grudge, shall be classified as political prisoner.”

The Act further explained, “For the purposes of this clause, (a) any offence committed or alleged to have been committed in furtherance of any political or democratic movement or any offence arising out of an act done by an individual with an exclusive political objective free from personal greed or motive shall be a political offence.”

However, after coming to power in 2011 with the promise of releasing political prisoners jailed during the Left rule, the Trinamool Congress Chief Mamata Banerjee did a volte face. In October 2012, after the Calcutta High Court granted political prisoner status to seven persons jailed on charges of being associated with the banned CPI(Maoist), the Congress-led UPA government’s P. Chidambaram-led home ministry advised the state to amend the Correctional Services Act, 1992, to block members of “terrorist organisations” from getting the status of a political prisoner.

The Mamata Banerjee government heeded and the relevant sections were amended on August 27, 2013, to exclude members of banned outfits. In most cases, people arrested for association with banned outfits were the ones who fought for or demanded political prisoner status. Their exclusion ended India’s brief tryst with formal acknowledgement of ‘political prisoners’.

Snigdhendu Bhattacharya is a journalist, author and researcher

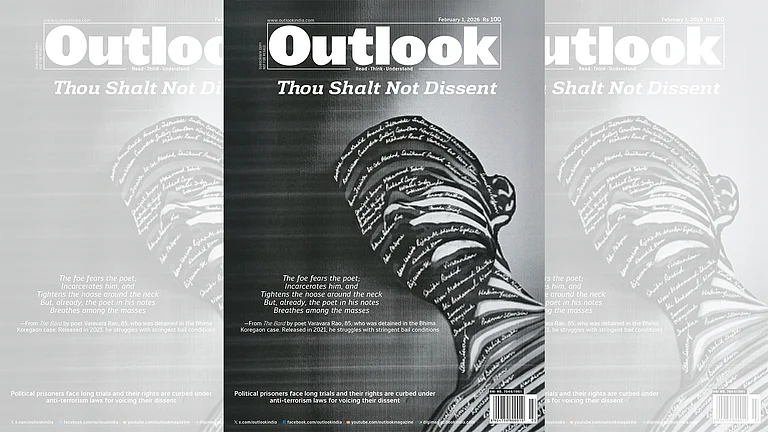

This article is part of the Magazine issue titled Thou Shalt Not Dissent dated February 1, 2026, on political prisoners facing long trials and the curbing of their rights under anti-terrorism laws for voicing their dissent.