HONG KONG

Globalisation has impoverished some, enormously enriched others – China being a prime beneficiary of the latter – and closely connected far corners of the world. These growing connections have brought instant success to people and products, but they have also put countries under global scrutiny. While basking in the global adulation for its unprecedented economic growth and brilliant Olympic spectacle China, however, rejects the other side of connections. While Beijing is happy to go out into the world to export its goods, services and ideas, it finds fault with critical comments and scrutiny that come its way. In fact, China seems to believe that it can interfere in the internal affairs of other nations without entertaining any dialogue about is own domestic policies.

As China’s economic power grows – thanks to Globalisation – it seems increasingly prone to use that power to oppose the other natural outcome of Globalisation. With the People’s Republic celebrating its 60th anniversary on October 1, it is time for China to resolve this anomaly.

In theory, Globalisation brings societies closer together, fostering the emergence of common standards. Engagement and integration requires a free flow of information and information by definition does not respect borders.

Hence, it stretches the bounds of logic for China to insist that it does not interfere in the internal affairs of other countries, and to demand that other countries stay out of China’s internal affairs.

Logical or not, Beijing is not budging from this position, which is largely used to prevent foreign eyes from prying into what is going on in China, especially where human rights are concerned and the way Beijing treats minority populations, such as people who live in Tibet and Xinjiang

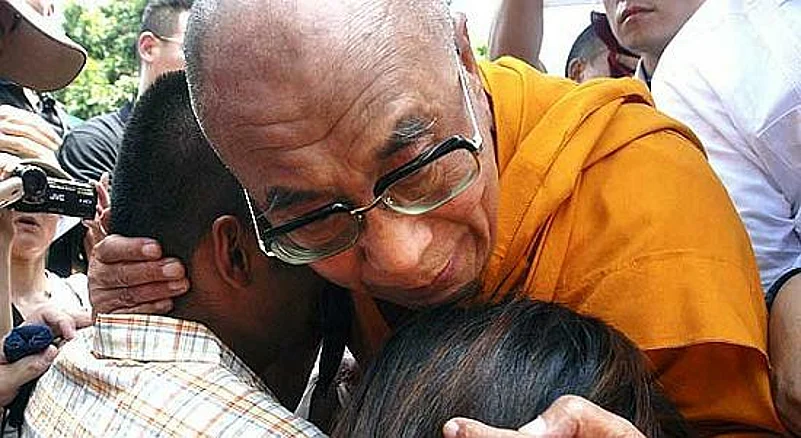

China’s charges of interference in its internal affairs have more often than not been triggered by meetings between the Dalai Lama, the head of Tibetan Buddhism, and foreign leaders. After French President Nicolas Sarkozy met with the Dalai Lama last December, He Yafei, deputy foreign minister, said, “The meeting grossly interfered in China’s internal affairs, severely undermined China’s core interests, gravely hurt the feelings of the Chinese people and damaged the political basis of China-France and China-EU relations.” Grave charges indeed.

At the time, Sarkozy insisted on his right to meet whomever he wanted. “It’s not for China to fix my agenda, or to dictate my meetings,” he said.

As for the Dalai Lama, China’s position was stated again by a Foreign Ministry spokesperson this month. “We are firmly opposed to the Dalai Lama’s engagement in separatist activities against China in any country and in any name or identity,” she said.

In early September, for example, the Dalai Lama was invited to Taiwan to minister to the spiritual needs of those who survived a devastating typhoon that precipitated mudslides, killing hundreds. While there, he did not engage in political activities and was not received by senior officials.

But China still objected. A spokesman for the State Council’s Taiwan Affairs Office declared that China opposed the visit “in whatever form and capacity” because the Dalai Lama “under the pretext of religion has all along been engaged in separatist activities.”

Indeed, China sometimes appears to demand that other countries yield part of their sovereignty in order to accommodate Beijing even in the case of film festivals.

When organizers of the Melbourne film festival recently decided to show the film “The 10 Conditions of Love,” a documentary about exiled Uyghur activitist Rebiya Kadeer, China objected.

The Chinese Foreign Ministry said the film “hurt the feelings of the Chinese people.” A Chinese diplomat telephoned the festival’s director demanding that the film be dropped. Some people may have seen that as interference in Australia’s domestic affairs.

What it comes down to is that China wants other countries to boycott the Dalai Lama—and others whom it labels as “separatists,” like Rebiya Kadeer—and refuse to issue visas to them. Of course, issuing a visa is a country’s sovereign right, but Beijing has relentlessly pressed other countries to bow to Chinese pressure and not issue such visas.

When South Africa earlier this year refused to issue a visa to the Dalai Lama, the Chinese foreign ministry exulted: “China applauds the position of those countries that respect China’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, adhere to the one-China policy and oppose the independence of Tibet.”

As far as China is concerned, anyone who offers a platform to the exiled Tibetan leader is interfering in China’s internal affairs.

And yet, if China had handled its internal affairs better, perhaps there would not have been a Tibetan uprising in 1959, with tens of thousands of Tibetans leaving their homeland for exile in India. Perhaps China should consider the possibility that it should from time to time listen to outside advice about how it handles its internal affairs.

Recently, China’s charges of interference have extended to the foreign media, whose job after all is to report on what is going on in the country. The People’s Daily, China’s official newspaper, published an online report on July 14 on the July 5 riot in Urumqi, in Xinjiang. It neatly presented two columns, one captioned “The Truth” and the other “Reports by Western Media.”

The truth, it said, was that the riot was “instigated and masterminded by the World Uyghur Congress led by Kadeer.” But western media reports, instead of saying so, reported what Kadeer had said in her own defence.

The truth, it said, was that the death toll from the violence stood at 184. Yet, the western media reported allegations of 500 Uighurs killed, or even higher numbers.

The People’s Daily did not simply accuse the western media of bias. It implied that the mass media was “a political tool” being used by western governments to interfere in China’s internal affairs. The proper way for western journalists to behave, it appears, is to report as truth whatever the Chinese government says.

China has been one of the principal beneficiaries of Globalisation. It now boasts the world’s largest foreign currency reserves as a result of foreign investment and trade. But it is resisting the tide of greater integration in other areas and, increasingly, appears to be asserting a right to control its citizens overseas and even over what foreigners can or cannot do when they interact with China or its citizens.

True, Globalisation resulted in images of the Tiananmen Square military crackdown being beamed into living rooms around the world and subsequent sanctions against China. But Globalisation also meant real time reporting of the Sichuan earthquake last year and the flood of sympathy and material support for the Chinese people.

The concept of non-interference in internal affairs is actually a European one. But in modern times it has been used largely by countries with something to hide, especially where human rights are concerned. It would be great if, with the celebration of the 60th anniversary of the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, Beijing could decide on a much more open policy and not hide behind the veil of “internal affairs.”

After all, China prides itself in having signed more human rights treaties than the United States. But, in signing a treaty, each country in effect agrees to give up part of its sovereignty. The spirit of these treaties is that a country agrees that its human rights performance will no longer be considered purely its domestic affairs and can be dissected by foreign governments, NGOs and individuals. China, now a mature 60 year old republic, will take a big step forward if its actions reflect this principle.

Frank Ching is a Hong Kong-based writer whose book, Ancestors: 900 Years in the Life of a Chinese Family, was republished this summer in paperback. Rights: Copyright © 2009 Yale Center of the Study of Globalization. YaleGlobal Online