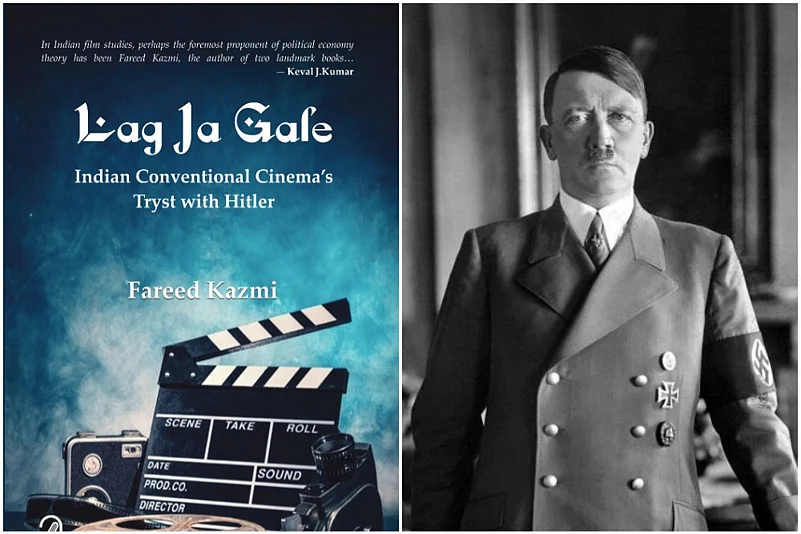

Cinema draws its significance in any society not only through entertainment but also through the ideological injection done through it. Cinema proficiently promotes a vision of society it is bound to get shaped in. Hereby, understanding Indian cinema through the realm of Hitlerian ideas becomes interesting which is done in the book Lag Ja Gale: Indian Conventional Cinema's Tryst With Hitler. The latest book written by Fareed Kazmi situates itself at the focal point of explaining the everyday appearance of fascist tendencies by analyzing the conventional cinema of India. The author develops an analogy between conventional cinema and Nazism in Hitler’s Germany.

The book brings in an extensive analysis of two categories of worldviews - Worldview of Hitler (WOH) and Worldview of Cinema (WOC). The Worldview of Hitler is an all-encompassing worldview promoted by Hitler through his writings, speeches and acts. The worldview of cinema means the dominant ideological stimulation done by conventional Indian cinema.

The central argument espoused in the book is that there exists a symbiotic relationship between the worldview promoted by the conventional Indian cinema (WOC) and the worldview of Hitler (WOH). Kazmi finds that Indian conventional cinema, as a tool with an impressive capacity for mass outreach, overlaps the Hitlerian discourse.

“Hitler might be dead but his ideas are very much alive. Coupled with the alarming growth of right wing forces almost all over the world and the near decimation of the left, he must indeed, be a happy man. But even Goebbels, who had the foresight to understand the power of cinema, would never have dreamt that at another time and another place, in far-flung India, the WOH would be heavily imbued in their WOC," he writes.

Conventional cinema, the author finds, is propagandistic in nature. The author argues this by analysing several movies belonging to conventional Indian cinema. In a total of five chapters, the book takes us through the landscape of conventional cinema and minutely analyses the portrayal of the protagonist (hero) & villains in it. It also engages with the art of deflection used in the cinema, making it a perfect propagandist material as well as how the worldview that both creates is preserved and penetrated.

The construction of the protagonist as Messiah (emancipator) in both WOH & WOC is done on a similar ground. Just like Hitler who is dismissive about the broad masses and calls for a proactive role of the superhero, Indian conventional cinema passionately glorifies the heroism of one man i.e. the hero. The messianic transformation of hero remains quintessential in conventional cinema where the protagonist has nurtured some extraordinary qualities. These qualities help it in rescuing society from wrongs. The author mentions that the binary between the ordinary and the extraordinary constitutes the cornerstone of all conventional films.

The demons i.e. villains in the Indian cinema who are abused as Gandi Nali Ke Keede, are depicted as ‘an enemy of the people’. Kazmi finds that the construction of villain in both WOC & WOH delineate villain as the sole problem of all miseries and sufferings. Self-appointed vigilantes who unshackle themselves from all legal and constitutional constraints, are feted in both the worldviews to win over the supposed ‘enemy of the people’.

The author also demonstrates that a category of new villains in Conventional cinema started in the 90s. These new villains were Muslim shown as dominant caricature for villain. They were mostly as terrorists in homeland/foreign land (Kurbaan, Holiday), Kashmir (Roja, Fanaa), across the border (Sarfarosh) etc. This blatant Islamophobic depiction of villains continues even today with much greater intensity. It transfixes the identity of the enemy into the collective consciousness of ‘broad mass’ to exert their anger against, similar to the demonic construction of Jews by Hitler in Nazi Germany.

The art of deception used in conventional Indian cinema where the transition from ‘sufferer’ to ‘fighter’ remains important for ‘righting the wrong’ and ‘bringing justice’, is similar to how Hitler appealed to vigilantes against Jews to correct the wrongs committed by them.

The important section in the book remains where the author does an in-depth critical analysis of cult-classic movies like Mother India, Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge and Hum Apke Hain Kaun. All of them commonly defend the entrenched structure, dominant social belief system, patriarchy and henceforth remain the custodian of the social conservativeness and orthodoxies by paving no way for rebellion.

Critiquing DDLG, the luminary of Bollywood romance, author writes: ‘Ostensibly, though DDLJ appears to be about the grand passion which has scalded and singed two souls, but in actuality, it is about justifying a certain hierarchy, code of conduct, behaviour pattern, cultural values, way of seeing the Indian way, all of which validates patriarchy, and the attendant power equation.’

Throughout the book, Kazmi ascertains the relationship existing between conventional Indian cinema and the ideas of Hitler. The tryst exists and conventional cinema works in penetrating cultural fascism in everyday life. The book does the parallel comparisons of the twin worldviews which helps the reader to grapple the arguments without any complexity.

The book, in relation to the present-day majoritarian Hindutva politics engulfing India, could amaze and scare the reader, as it juxtaposes the developments of Nazi regime with the current time. The book becomes an important read as it engages itself with the politics of conventional cinema and its agency. It shows how a particular form of worldview is shaped and permeated in society through cinema. Lag Ja Gale remains an important theoretical intervention in the filmic discourse and gives a new entry point to readers in understanding the ideological underpinnings of conventional Hindi cinema.

(Himanshu Shukla finished his masters in political science from Delhi University and is currently working as a researcher with Greenpeace)