This occasion makes me think of Ashis Nandy’s great remark in The Tao of Cricket, that ‘cricket is an Indian game accidentally discovered by the English’.

Tiger— in the mind’s eye— aquiline, still, slight, swift, hawkish. On the field he had presence, a regal touch; one’s eye would be drawn to him, as eyes have been drawn to Imran Khan, Viv Richards, Ian Botham. A proper arrogance, or as Bishan Bedi put it, an ‘imperious charm’. He was of course a prince, being brought up in the palace in Pataudi. His mother was the Begum of Bhopal, his father the previous Nawab who scored a hundred for England at Adelaide in the Bodyline series.

As a person, Pataudi was, as Hubert Doggart has said, a lovely man. He was laconic and understated, wry not slapstick. He once convinced a team member that the great white-marble Victoria Memorial in Kolkata (one of the Raj’s great monuments) was another of his personal palaces— a story whose English analogy might perhaps be one of the other Sussex amateurs announcing to a young pro on his first visit to London that St Paul’s Cathedral was his private church. When Tiger was asked, after his maiden Test hundred in 1962 against Ted Dexter’s MCC team, when he first believed he could play Test cricket after the injury, his reply was: ‘When I first saw the English bowling’— which reminds me of Mahatma Gandhi’s response to the question (put to him in 1933): ‘What do you think of Western civilization, Mr Gandhi?’ He replied: ‘I think it would be a good idea.’

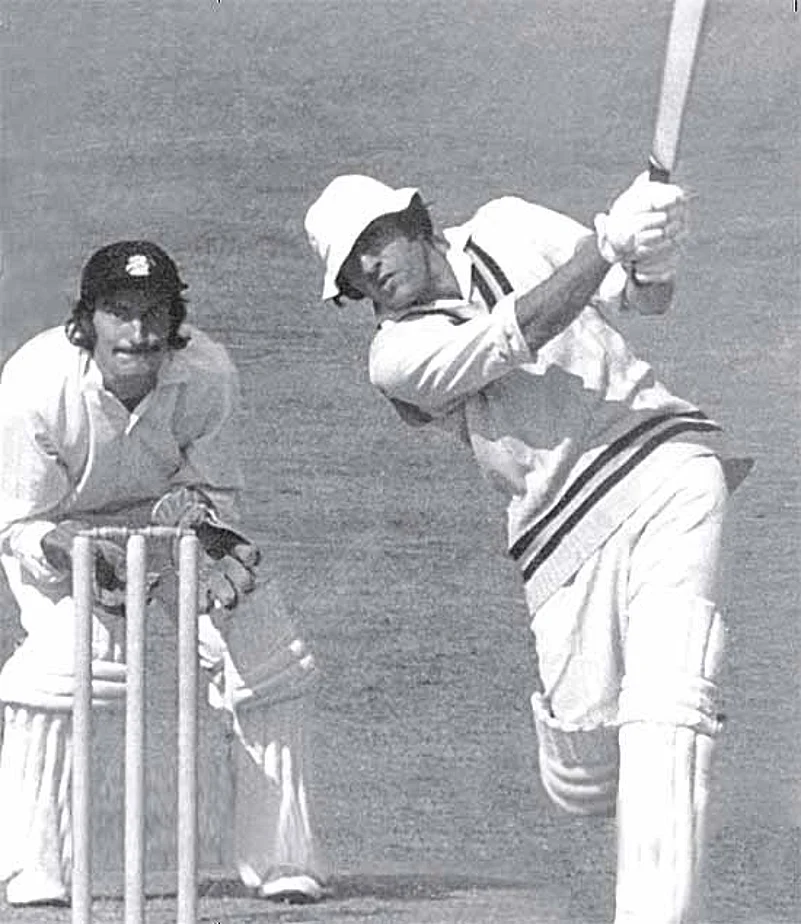

As a batsman, Tiger was by temperament a dasher, who, contrary to Indian batting approaches of the ’50s and ’60s, hit over the top; at the age of fifteen, he kept lobbing Robin Marlar back against the sight screen for Winchester against the Sussex XI of which Marlar was captain; Marlar said he enjoyed it the first four times. (After the injury, Tiger was inevitably more circumspect, even, at times, tentative.)

As captain of India and, for a year, of Sussex, he insisted on total commitment in the field; whites were to be got grubby, regardless of the— as he put it— abysmal service provided by English laundries. Bishan Bedi again: ‘On my debut, he didn’t have much to say about my bowling beyond acknowledging with a nod of the head that I was doing all right. But he had plenty to say about my fielding.’ He brought the Indian team together as a unit, rather than the group of individuals speaking different languages and sometimes forming cliques, whether from the Punjab, Bengal, Mumbai, Hyderabad or Bangalore. He also had one Test wicket to his name, at Kanpur, in 1964, when he took the second new ball. ‘Cowdrey lbw Pataudi 38.’ The appeal was answered by the umpire with the words: ‘That’s out, Your Highness’. Tiger claimed it was a sound decision.

In a way, Tiger was the Denis Compton of Indian cricket— the first cricketing superstar in India whose appeal involved so heady a mix of brilliance, charm and charisma. To top off the fairy story, he married the glittering film star Sharmila Tagore— someone who in India’s celluloid pantheon seems to me to have been a combination, if I may say so, of Peggy Ashcroft and Marilyn Monroe, with a bit of Joan Sutherland and Margot Fonteyn thrown in.

Aside from Tiger’s aristocratic air, he also had the common touch. Cricket writer John Woodcock told me a story of meeting a country labourer he knew whilst fishing on the banks of the Avon. This fellow turned out to have been one of the beaters at a partridge shoot at Druid’s Lodge that Tiger had been part of, and clearly had taken to him as one of his own. And Peter Vallance, who played with him for Wisborough Green, a village in Sussex where his guardian lived, spoke to me of Tiger’s approachability and of his pleasure in village green cricket— Tiger played for the village on a Sunday in the middle of a match against Yorkshire at Hove. There was, he also said, ‘nothing of the Nawab about him’; I imagine that to be not quite true, but what was true was that there was a lot of the ordinary man about him as well as the Nawab.

I think he was probably a bit of a rascal too. He once invited Woodcock and Henry Blofeld to the back of a dry Indian Airlines flight from Mumbai to Kolkata to share a bottle of vintage brandy he had quietly removed from the cellars of the palace in Bhopal. More notoriously, he got into trouble for a hunting incident. A friend of mine, the historian Ramachandra Guha, who wrote the excellent book on Indian cricket, A Corner of a Foreign Field, told me how, when they were both on a TV panel together shortly after that affair, Tiger, surrounded by intellectuals of one kind and another, murmured that no doubt he had been invited as the panel needed a convict to provide balance.

By repute, or possibly by scurrilous rumour, Saif Pataudi had a streak of his father in him. Shortly after the younger Pataudi’s leaving Winchester, a young boy in the same house announced that they were glad Saif Pataudi had gone, because now they could get onto the billiard table. Did he spend a lot of time playing, came the natural question. No, said the boy, but he spent a large amount of time asleep on it.

I played against Tiger in 1956, when he was fifteen and I was fourteen, for Middleton-on-Sea Sunday Eleven, a team that went all over Sussex, playing on often pretty and always rustic grounds, such as the one at Wisborough Green. I was in awe of this already renowned schoolboy. If my memory is right, our combined total for the day was two runs, and I outscored Pataudi.

By 1960, he was at Oxford. The following year I went to Cambridge, and we read about his achievements with admiration, even apprehension. He scored two centuries in a match against Yorkshire, with their full bowling attack, including Fred Trueman. County players spoke about his batting as unique. He had more than a touch of genius. And then, of course, the apparently innocuous accident happened, on the sea front at Hove; feeling no pain in his head, he had no idea that a sliver of glass had entered his right eye. The operation left him with 90 per cent sight overall; he required a contact lens in the bad eye. One problem was that he saw two of everything. The story he tells is that in his first important match after the injury, against MCC at Hyderabad, he got to 35 seeing two balls apparently six or seven inches apart, of which he found it more productive to play the inner one. At this point in his innings, he got rid of the lens and made the most of his one good eye, doubling his score.

This innings, like his life, ended prematurely, at seventy. But it resulted in his being picked for India; extraordinarily, only a few months after the accident. And he scored a hundred at Delhi in the fourth Test. He says it took him five years to get used to batting with what would seem to be a huge impediment, by which time he had been captain of India for four years. But there is another story about this. In 2001, Saba Karim, a wicketkeeper batsman who played thirty-five times for India, was hit in the right eye whilst keeping to Anil Kumble during an Asia Cup match in Dhaka. Tiger visited him in hospital, ‘making his presence felt without shouting from the rooftops’ as Karim put it. Tiger helped the younger man to accept fate and move on; to make those adjustments that make life worth living. Saba asked him how long it took him to recover. ‘Saba,’ he said, ‘I never recovered.’ But Tiger made a life, including, of course, a major cricketing life, for himself, despite the accident.

In 1963, he and I were captaining Oxford and Cambridge here at Lord’s. He scored 50 or so; we had a sporting game, in which those other sons of famous cricketers, Richard Hutton and Mike Griffith, also made half centuries. Tiger declared 45 runs behind, and we set Oxford 194 to win in 2 hours and 20 minutes. We had them six down for 110, at which point they called off the chase and the match was drawn.

Tiger won the respect of cricketers and followers all over the world. Ian Chappell came from Sydney to Mumbai to speak in his honour last December. Ian described his two innings in the Melbourne Test in 1967. As Ian put it, not only was he batting on a green pitch in bowler-friendly conditions; not only was he coming in at 25 for 5 after being put in to bat, with one of the leading fast bowlers of his time against him; not only did he only have one fit eye. He also had only one fit leg. Chappell remembered two shots during that first innings: a hook that went in front of square for a one-bounce four on the biggest square boundary in world cricket, and a back-foot straight drive off McKenzie over mid-on for another one-bounce four. Chappell remembers asking him how it was that he would come in to bat after intervals with a different bat; Pataudi said he picked up the one nearest to the dressing room door. Once again, shades of Compton; a sense of a capacity to do things other top players could never emulate, the sense of his being a law unto himself. Compton too borrowed bats. Both of them were incredibly untidy. And I remember Don Bennett speaking of the awe his fellow Middlesex players felt about an innings of 150 out of something like 220, on a drying pitch, against Sussex, I think.

The last paragraph of his book Tiger’s Tale includes the following: ‘In the country of the blind the one-eyed man is king. In the keen-eyed world of cricket, a fellow with just one good eye and a bit has to settle for something less than the perfection he once sought.’ And of cricket itself he wrote: ‘It is difficult to explain the appeal of cricket, but to me it has charm, style and depth.’

I’d like you to stand to drink the toast: in celebration of Tiger Pataudi, his family, and the special game he loved and adorned.

Excerpted from a speech Mike Brearley gave on Pataudi at Lord’s last June