"Truth is stranger than fiction," goes the old saying. Some real-life stories are so improbable that if you tried to put them in a movie nobody would buy it. And yet the movies do demand, from those of us who love them, no small measure of suspended disbelief. Salman Khan takes out three goondas with one flying kick. Aamir Khan goes to college. Krishna appears on Earth in the form of Akshay Kumar. And while the movie is going on, some of us, at least some of the time, are willing to buy into the particular rules of its universe.

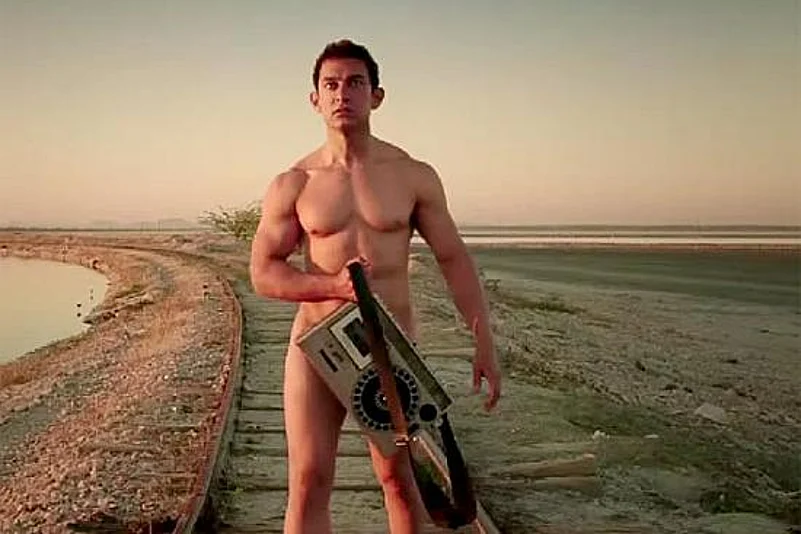

The responsibility for creating suspension of disbelief lies with the storyteller. The filmmaker must create a world that is internally consistent and engaging enough for the viewer to set aside her critical objections and accept the story's axioms. This is the storyteller's task, but whether the storyteller succeeds is entirely subjective, lying in the mind of the viewer. Different viewers — or even the same viewer on different days — apply different standards to different films, and what draws in one viewer may be jarringly ineffective for others. Admirers of Aamir Khan, perhaps, have an easier time accepting him as a college student in 3 Idiots, or a space alien in PK, than those who find him pretentious and annoying. In Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi, Shah Rukh Khan plays a nerdy office-worker, Suri, who puts on an outrageous cool-guy act to please his young wife; it's completely absurd, but Shah Rukh Khan's fans may enjoy the shtick and swagger so much that they don't fret about whether a guy like Suri could actually maintain such a charade. And folks who buy tickets to Salman Khan's masala flicks would be disappointed if he didn't perform physics-defying melee moves.

For sure, suspension of disbelief is the raison d'etre of a certain class of films, but we are more willing to grant it to films in that class than to films that take themselves more seriously. Put another way, we hold different films to different standards of realism. The same people who complained that Byomkesh Bakshy unrealistically ate aloo bhaja with his chai in Dibakar Banerjee's Detective Byomkesh Bakshy! will joyfully watch long-lost brothers reuinted, however improbably, in the classic movies of Manmohan Desai. And the same folks who scoff at Hindi films for characters bursting into song might raptly await the next installment of their favorite Hollywood superhero franchise. Suspension of disbelief is a necessity for watching any film, but it can only succeed up to a point, and where that point lies is not only subjective but varies from film to film.

The overall tone of the film plays a huge part in drawing the line at which credulity can be strained no further. In masala films we expect the narrative to stray way outside the bounds of plausibility. Seeta aur Geeta and its ilk offer twins separated at birth and accidentally switching places as adults. Movies from Don to Satte Pe Satta give us doppelgangers, unrelated characters who happen to look alike down to the last whisker. So does the ghost story of Bimal Roy's classic Madhumati, which goes down easy because the entire film is staged like a fable, right from its opening scenes on a proverbial dark and stormy night. Om Shanti Om is an acceptable update; it, too, occupies a fantastical space, and to demand realism from it is to profoundly miss the point. But in a film like Reema Kagti's Talaash, so gritty and deliberately realist in tone, the presence of a ghost not just in a character's imagination but actually real within the world of the film is jarring — at least to some viewers. And the more hard and serious a film's theme, the less leeway audiences are apt to give in the details. The word "realistic" comes up a lot in discussions of films like Haider or Gangs of Wasseypur.

Sometimes suspension of disbelief is readily achieved because the story is so patently allegorical that its outrageous events can't be meant to be taken literally. When the heroic falcon of Coolie swoops in to save the day again and again, it is not because Coolie takes place in a magical universe of sentient birds. Rather, he is a metaphor for God (named Allah Rakha, no less) in a movie packed to the gills with metaphors for God. Lagaan is a different embodiment of a similar theme; the colossally improbable victory of the ragtag village novices against the English cricketers is accepted, and perhaps even all the more satisfying, because of its allegorical value representing Indian unity in defiance of colonial oppression. Amar Akbar Anthony also presents the theme of Indian unity in belief-defying narrative form, as the three unknowing brothers, one Muslim, one Hindu, and one Christian, join together in a simultaneous donation of their very blood to their biological and allegorical mother.

Most of us, when we watch a movie, want to be transported. We want to engage with the story, identify with the characters, and enter a world that is reflective of, if remarkably different from, our own. This is not to say that we always want absolution from thinking, though some certainly do look to movies for pure, brain-free escape. Even when we want to think critically while watching a movie, we want to apply that thinking to the movie's substance, its messages and themes — not to whether the narrative makes sense. Straining suspension of disbelief interferes with that experience; it breaks the viewer out of the narrative and forces engagement on the wrong level. And so for the most part we readily give ourselves over to the wisdom of space aliens, to the bond between long-lost siblings, to lovers bursting into choreographed dance. Suspension of disbelief isn't just a necessary part of the movies — it's part of why we love the movies.

Beyond Belief

Suspension of disbelief isn't just a necessary part of the movies — it's part of why we love the movies.

Beyond Belief

Beyond Belief

Published At:

MOST POPULAR

WATCH

PHOTOS

×