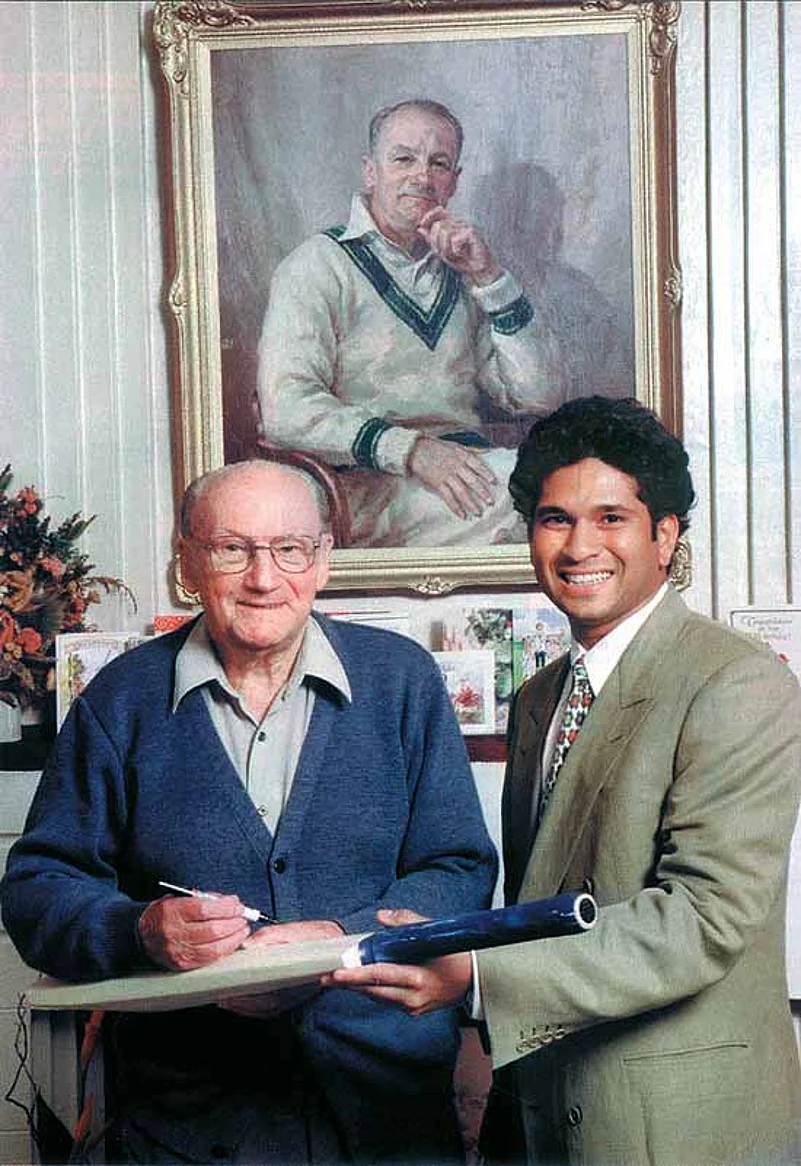

Bradman. Tendulkar. Even on their own as words, they have an incantatory power. Put them together in a sentence and they combine like a magic spell. ‘Bradman Tendulkar’: guaranteed to make bowlers disappear. Stick a little ‘v’ between them, too, and you’re inciting one of the most fervid of sporting debates, even if it is one that usually generates more heat than light.

I mean, Bradman v Tendulkar? Why not Shakespeare v Dickens? Or Tagore v Naipaul or Narayan? Or apples v oranges? Because on reflection, there isn’t a lot of the common coinage that makes for straightforward comparison. Bradman arose 70 years ago in a country of six million people; Tendulkar is the hero of a thousand fights in a land of 1.3 billion. Bradman played cricket in two Test countries, Tendulkar in ten; worldwide war left its ugly slash across Bradman’s career, while Tendulkar has lived mostly amid peace and plenty.

The careers of both span roughly two decades, but are as different as their statistical breakdown: Bradman’s encompassed 52 Tests and 182 other first-class matches, Tendulkar’s has featured 176 Tests, 442 one-day internationals, 103 further first-class games and then some ...so far. In Bradman’s time, bowlers were roughly equal partners in the cricket enterprise; in Tendulkar’s, thanks to a cricket calendar that seems to squeeze 15 months activity into every 12 months, they’ve been reduced to serfs in a feudal batting society. Bradman’s challenges came chiefly from his opposition; Tendulkar’s challenges flow, increasingly, from himself, finding new ambitions, new directions, staving off satiety.

The capping century: After the 50th Test hundred at Centurion, SA, Dec 19, 2010. (Photograph by DUIB DU TOIT/Getty Images)

Don’t underestimate the difference in equipment too. Pick up a bat of Bradman’s and prepare to be amazed that he spread such terror and dismay: it is as light and slim as a switch. Impregnated with oil, it would have been a little heavier to use, but not much. Wield a bat of Tendulkar’s and...actually, it gives you the shivers. It looks almost as thick as Bradman’s was wide, yet picks up like something half its actual weight. You’ll also grasp why, while Bradman hit only six sixes in his international career, Tendulkar has hit two hundred and forty-seven. Add to this the advent of the helmet and of feather-light protective gear, and not only can Tendulkar’s blessings can be seen to have abounded, but the difficulty of comparison can be gauged.

If their crickets are perhaps remote from one another, however, their fames may make more fruitful comparison. Bradman was and Tendulkar has been their country’s best known local and international figures for much of their lives. It is one thing to become famous; it is another to remain famous. Fame requires great deeds; its continuation involves an avoidance of the pitfalls that follow. Their feats have been not only to succeed but also not to fail: no two cricketers in history have disappointed their countrymen so seldom.

They made batting, that most complex, various and precarious of arts, appear as secure an occupation as going to work in an office. Cricket is proverbially a funny game, full of chance, but in their hands luck, coincidence and fluke seem controllable, replicable, even predictable. On being wished “good luck” by a comrade as he went out to bat, Geoff Boycott is meant to have retorted: “It’s not luck. It’s skill.” Bradman and Tendulkar come as close as any cricketers to rendering that an absolute truth.

They had an appeal, too, that struck countrymen in the heart. Both have been progressive rather than traditional figures. They symbolised new possibilities—that their respective countries could be better than all the world, that they could rise above national ignominy. Bradman achieved fame during the Great Depression, Tendulkar in the aftermath of India’s 1991 economic crisis. They became captives of their fame—wary, reclusive, even a little aloof—but their popularities have made them wealthy. They have sought out commercial opportunities without incurring public displeasure. On the contrary, their peoples have cheered them on.

In the early years of Bradman’s career, he seriously entertained the idea of abandoning Test cricket because the rewards available in the Lancashire leagues were so lucrative; he shifted states in search of greater financial security when it was virtually unheard-of. In the early years of Tendulkar’s career, he put himself in the hands of the savvy Mark Mascarenhas, who turned him into his country’s biggest billboard; his net worth now exceeds $1 billion. Nobody begrudged either of them the fortunes they accumulated. What Ray Robinson wrote of Bradman is true of Tendulkar too: he did not make money so much as overhaul it.

Marked man: Mascarenhas made him our biggest billboard. (Photograph by RABIH MOGHRABI/AFP)

In doing so, they became fullest expressions possible of the professional cricketer in their eras, exploring the limits to the potential for the monetisation of cricket talent. These possibilities had until Bradman’s era remained untapped outside England, which for much of the 20th century had the world’s only full-time professional cricket circuit; Tendulkar brought them to the greatest cricket bazaar of all. Bradman began the displacement of England as cricket’s citadel; Tendulkar has completed it. Bradman made contemporaries see that a man with a bat could change the world; Tendulkar wakened us to by just how much. If Bradman could be expressed as a question, the answer would be Tendulkar.

The author is an Australian journalist and cricket writer