- Archival records put the Allahabad Kumbh Mela as a post-Mutiny phenomenon

- The prayagwals, or Brahmin pandas, created the legend to slip past British controls

- No mention of it in the Puranas or travellers' accounts; first reference appears in government records only in 1868

Inevitably, this led to conflicts. Especially with the prayagwals, the Brahmin pandas who guided pilgrims through the rituals for hefty donations. They resented the government squeezing its share out of the pilgrims. More serious was the loss of hegemony, with the British imposing more and more constraints on the mela trade. In 1815, for instance, they clamped a new system of policing on the fair. It led to a strike by 4,000-5,000 prayagwals. But they had to give in eventually.

Then, there were the Christian missionaries who set up rival camps at the mela. They scoffed at the sadhus and pandas, and at the practice of turning prayer into commerce. The squabble for pilgrims' ears and faith sometimes turned ugly, says Maclean. One missionary from Pennsylvania, for instance, stoned a Naga sadhu to prove he was as vulnerable to pain as other humans.

The conflict reached its peak in June 1857, when the prayagwals—1,500 families in all—joined the revolt. They attacked the mission press and churches in Allahabad and took control of a pontoon bridge in order to stop communication over the Ganges. Before the outbreak, the priests had been instrumental in spreading the unrest, even going as far as to proclaim, in the words of the Allahabad collector, that "British power is to close this year". The very first act of the notorious Colonel James Neill, who arrived for a brutal 'pacification' of the city, was to attack the prayagwals. Many were hanged, others fled into jungles and neighbouring towns to "save their necks". Survivors were persecuted, their land confiscated. It's very likely, says Maclean, that "some of the confiscated land constitutes today's mela grounds".

Unsurprisingly, there was no magh mela in the year after the Mutiny. But by 1859, pilgrims were trickling in again. By 1860, the prayagwals were defiantly flying anti-British insignia instead of the traditional symbols on the flags that each panda family used to direct their flock of pilgrims to where they sat on the river bank. The flags now bore symbols of victorious pandas rising over their fallen enemies, the Whites. Maclean says she was intrigued by the emblems, some of which survive to this day. Anti-British sentiment apparently was good for business. And the prayagwals went at it with relish, flying their seditious symbols literally under the nose of the British. "It is not difficult to divine, from the scowls and mutterings of men as Europeans pass by," wrote a British reporter in 1860, "what they would do if they dared."

But if the prayagwals did not dare take on the British directly, they were learning to fight back in other ways. In 1860, they formed a sabha and registered with the British government. Their aim: to protect and preserve their right "to conduct rituals and accept donations". Just when they decided to rename every 12th magh mela as a Kumbh mela is not clear, says Maclean. But her guess is that it was a result of a ploy to outwit the British who argued that the magh mela was not really a religious fair at all in order to shut down the "nuisance". Interestingly, the first reference Maclean found to a Kumbh Mela in Allahabad pops up suddenly in an 1868 report on sanitation, in which Allahabad's magistrate G.H.M. Rickett mentions in passing a forthcoming Kumbh in 1870.

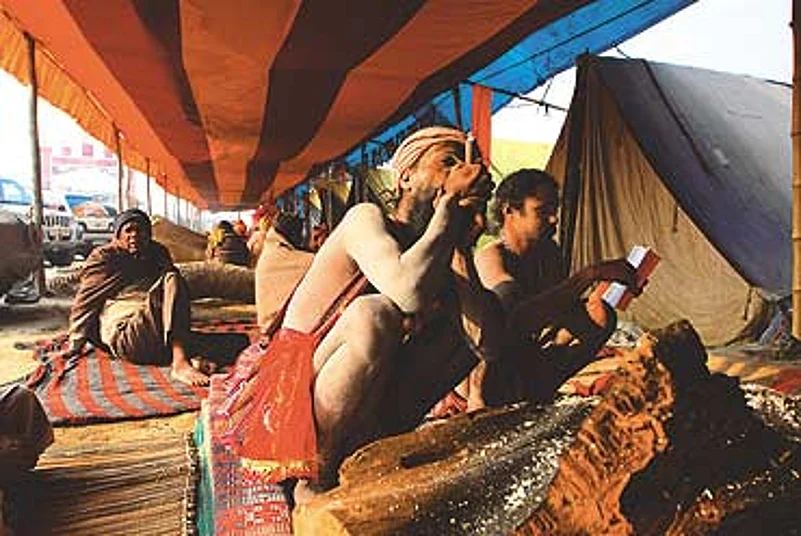

To turn a local bathing festival into a Kumbh, Maclean points out, the prayagwals would have to get the cooperation of the sadhu akharas. "They did not cook it up together, but they took their cue from the movement of the sadhus," she says. The sadhus had halted at Prayag since puranic times, but it was Haridwar they were headed for. For the sadhus, she states, Haridwar was an infinitely better venue for a Kumbh Mela. Also, the akharas fiercely fought each other because the victor won the right to tax pilgrims. Further, the stakes were higher for them in Haridwar where the trade was in elephants, camels, bullocks and horses. Compared to that, the Allahabad fair was peanuts: trinkets, pots and pans, and "articles of the most trifling value, but of every possible description". But after the mutiny, things were changing, even for the sadhus. They lost their right to collect pilgrim tax, for one. They were stripped of their arms, and some of them were picked up under the Vagrancy Act. The reinvention of the magh mela into a Kumbh couldn't have come at a better time for them. At the Kumbh they could parade naked and once more carry arms, even if it was now purely ceremonial. And instead of one Kumbh, they now had two in the same 12-yearly cycle to exercise their "religious" freedom, unhampered by British constraints. At first, there was some confusion over the dates, of course. But the glitches have gradually disappeared, yielding a regular cycle of a Kumbh or an Ardh-Kumbh once in three years at four places: Haridwar, Allahabad, Ujjain, Nasik.

It was an invention the British were willing to wink at, claims Maclean. "Organising the mela to the pilgrims' satisfaction was a way of earning their goodwill, and the creation of an arena in which the theatre of sadhu hegemony could be periodically rehearsed under controlled conditions partly helped contain the sadhus' potential as subverters," she concludes. Ironically, though, the creators of the modern Kumbh myth, the prayagwals, are now almost edged out of the mela to make way for a new kind of pilgrim: the tourist. But that's the beauty of the Kumbh Mela—it's forever changing in the name of tradition.