Prime minister Narendra Modi is an MP from Varanasi, home to some of the greatest Hindi writers and poets. Among them is Bhartendu Harishchandra, who died at the age of 34 in 1885, leaving behind in that short life a treasure trove of prose, plays and poems. Many see him as the father of modern Hindi literature and theatre. The fact that he was not a Brahmin but belonged to the Aggarwal Baniya caste could potentially make him even more appealing to India’s PM, whose non-Brahmin, subaltern hero image was an element in his campaign. Bhartendu had penned a poem on the mother-tongue, the first two lines of which translated roughly into English, read:

Progress lies in one’s own language (the mother tongue), it is the foundation of all progress.

Without knowing your own language, there is no cure for the pain of heart.

There are some who worry that the tyranny of Hindi chauvinism is upon us now, as PM Modi makes it a point to speak in Hindi and avoid English, which he understands perfectly well. So here’s a little detail that is not without some significance. Finance minister Arun Jaitley will be reading the Union Budget in English on July 10. Since that will be the most important statement of intent of the Narendra Modi government, watched by both Indian citizens and global investors, let us be clear that there is no anti-English pogrom that is about to be unleashed on the country.

Yet, a key aide to Modi says that, in their political assessment, one of the ways the Congress showed its disconnect with the people was when in the course of the campaign it kept fielding ministers who were fluent in English but struggled in the Indian languages. Modi certainly likes to have his hand on the political pulse and the BJP knows its victory is essentially a sweep of the Hindi heartland. Hence the emphasis on speaking in Hindi, especially by those who are from the heartland or represent it. At the swearing-in, most cabinet ministers, including Jaitley, took their oath in Hindi. It was only those from the south, such as Venkaiah Naidu, who preferred to do so in English.

This is, therefore, a regime quite different from the UPA where you could say the default language of policymaking was English. Most Congress ministers would address the media in English and some would offer to translate into Hindi. In the BJP, on the other hand, many just have their say in Hindi. Within the cabinet and the party, the debates are mostly in Hindi. It has led to the suggestion in some quarters that at its core this is a Hindi-Hindu-Hindustan push. That would be only partly true as there is complete clarity on not imposing Hindi on the unwilling southern states and to do business with the world in English when required.

One may also digress to highlight the importance of Hindi within the RSS, that may be headquartered in Nagpur, Maharashtra, but has always operated with the greatest organisational depth and intensity in central India. Modi’s own Hindi is far superior to that of the average Gujarati because of the RSS background. All the significant pracharaks of the BJP-RSS, from Govindacharya, a Tamilian, to the late Kushabhau Thakre, have always cultivated a fluency in a Sanskritised version of Hindi. It is quite natural for all of them to speak that unitary, standardised Hindi and ignore the inflection of the many lilting dialects of the language.

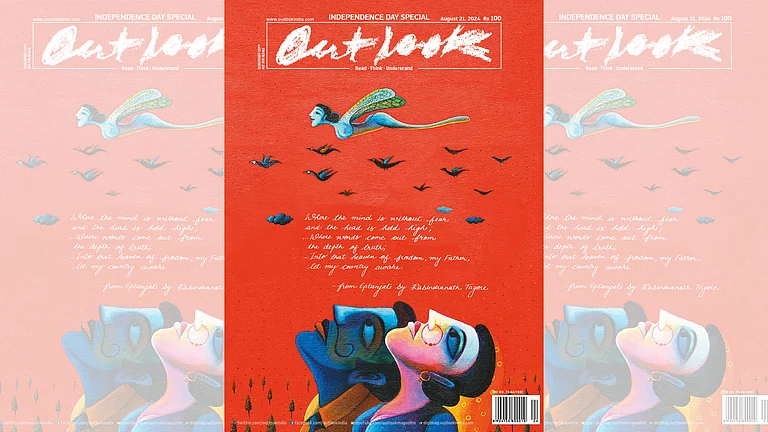

Photograph by Jitender Gupta

This is the Hindi of the Indian state about which the great actor Balraj Sahni would fondly recall friend Johnny Walker’s quip on the news broadcast on state-run TV—“Ab samachar mein Hindi suniye” (now hear Hindi in the news). The complex Hindu-Urdu issue has already left its imprint on Indian history. Urdu is a dying script in India, although the spoken language survives. Even within the Muslim community, many read the great Urdu poets in the Devanagari script. But to dwell on this chapter of our language struggles would be to stray from the main point of how the new regime relates to the old idea of promoting Hindi.

Many terms have been used to describe the present shift in Indian politics, including a comparison with the Conservative Party of Great Britain. But the Conservatives preserve privileges while the Modi regime will have no time for the liberal English-speaking elites who have had influence in the corridors of power in Delhi and dominated universities, faculties and quasi-government autonomous institutions. The Modi loyalists would wish to create a counter-establishment, but do they have a proven pool of talent to draw on, like the Conservatives in Britain? It is yet to be seen whether the managerial skills displayed in the campaign and the raw energy it tapped in the heartland have produced the sort of intellectual talent that is required to preserve institutions, create curricula, particularly in the liberal arts and humanities. Certainly, vocational studies would thrive under the current dispensation.

In the use of Hindi, there will also be a certain continuity with the other BJP prime minister—Atal Behari Vajpayee—who was a gifted Hindi orator with an altogether different style from Modi’s. In fact, at one stage, when Vajpayee tried speaking in English outside India, his trademark verbal skills were missing and he was advised to speak in Hindi and have translators. Modi has, from all indications, made up his mind not to fumble in any language he is not in complete control of. In Bhutan, for instance, he chose to speak in Hindi, while his external affairs minister Sushma Swaraj duly followed up with English.

Modi’s attitude to language, in fact, has many shades and nuances. Indeed, there’s a little-known fact about the Modi administration in its 12-year reign in Gujarat. As chief minister, the current PM actually promoted more English-medium schools under the government sector than any of his predecessors in the state. Although such observations are hard to quantify, a visitor to the state would not be too wrong to conclude that the level of fluency in English in the state is possibly not as good as that in other states or zones of India with equal levels of urbanisation. Gujarat is quite wedded to its regional language; its popular serials and a particular sense of humour are conveyed best in the mother tongue. Hindi is easily understood and spoken, but the best jokes are to be cracked in Gujarati. Outside the metros, English is of little use.

Yet, conversely, Gujaratis are very committed to globalisation, whatever language that may require. Historically, the coastline has been a hub of international trade, and today, 30 per cent of the NRIs in the US are of Gujarati origin, as are one-third in the UK. Because he was for some years cut off from the West, Modi turned East and his global drive included non-English-speaking economic powers such as Japan, a nation to which he will make a significant visit in August. He intends to leave his imprint on the world while speaking in Hindi but it would be stretching things to paint Modi as anti-English. Many of the people whom he relied on to run his campaign or some of whom he has trusted to manage his government are fluent in English. But even they would be well advised to brush up on their Hindi—not because language tyranny is in place, but because it’s just easier to communicate with the BJP, in government or outside, in Hindi.