The Law Of Controversy

A few of Justice Dipak Misra’s judgements in 2015-16

- Upheld charge of obscenity on a poem that allegedly denigrated Mahatma Gandhi

- Upheld Yakub Memon’s death sentence, overlooking fresh evidence that many felt merited a commutation

- Refused to order collection of data on how many employees from backward classes benefit from reservation in promotions and exempted states from providing reservation in promotions

- Held that national interest called for doing away with reservation in higher education

***

To be defamed, you need to be a “man of character”. Or so the law implies. Recently, finance minister Arun Jaitley felt he had been defamed and wanted to lodge a complaint. According to senior lawyer Indira Jaising, Jaitley had to bring along two friends to vouch for his “character”, as per procedure laid down in law. Last week, the Supreme Court gave a leg up to this 156-year-old law, the law of criminal defamation.

Though the UK abolished criminal defamation in 2009, India’s Supreme Court extensively quoted British jurists to uphold a law that was four centuries old in its country of origin. It was introduced here by the colonial government in the Indian Penal Code in 1860. In upholding sections 499 and 500 of the IPC, the two-judge bench shocked much of the legal fraternity who called the verdict “regressive”.

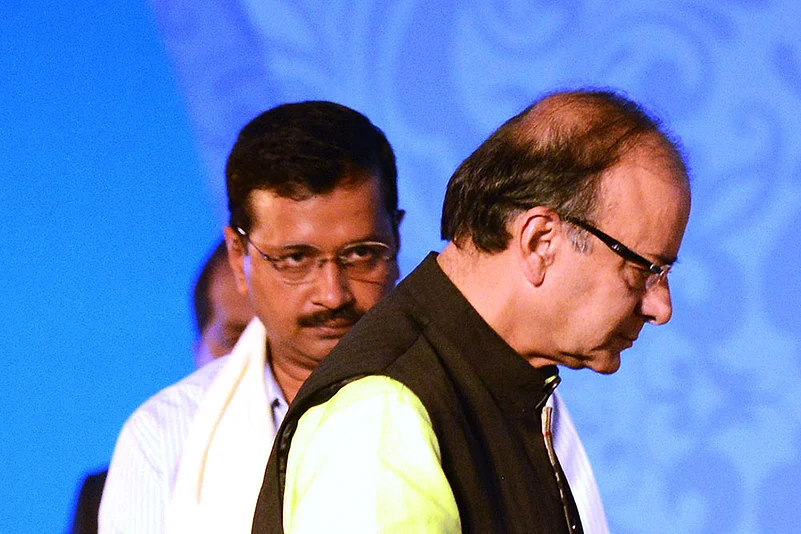

BJP MP Subramanian Swamy had challenged the law and the court clubbed it with similar petitions filed by Delhi CM Arvind Kejriwal and Congress vice-president Rahul Gandhi that called out the outdated law’s chilling effect on freedom of speech. A private complaint could lead to arrests and detention of unreasonable and disproportionate nature, the petitioners claimed. While Swamy and Rahul wanted the apex court to do away with the law, the BJP-led government has backed its constitutional validity through the attorney-general.

Politicians of all major parties have been hauled up several times for criminal defamation. Last year, Jaitley was summoned to answer sedition charges for a comment on the top judiciary. That case, though, was soon dropped and the judge suspended. Kejriwal joined the ‘defamation’ club after Jaitley and Nitin Gadkari filed separate complaints against him. Similarly, an RSS worker complained against Rahul and J. Jayalalitha against Swamy.

In a recent case in Kerala, the principal and 11 students of a polytechnic and later nine students of Sree Krishna College, Guruvayoor, were arrested and charged under criminal defamation for publishing material that the BJP thought defamed PM Narendra Modi in their respective campus magazines. In a Times of India op-ed piece, Amulya Gopalakrishnan pointed out how Jawaharlal Nehru has been slandered on the internet. Imagine if these trolls had to be charged with defamation!

The Supreme Court had earlier held that “actual malice” has to be established even for civil prosecution, and to have knowingly spoken falsely or with reckless disregard for the truth would amount to defamation and call for civil remedies. But the two-judge bench of Justice Dipak Misra and Justice P.C. Pant has now justified criminalising defamation by arguing that citizens have a fundamental right to reputation and that the “reputation of one cannot be allowed to be sacrificed at the altar of others’ right of free speech”. Defamation harmed the reputation of a person, they ruled, saying the right to life with dignity under Article 21 of the Constitution also protected a person’s reputation, who can file a civil suit and, simultaneously, a criminal complaint.

The judgement, say critics, neither explains how defamation can be deemed to be a public wrong and why criminalisation is a reasonable and proportionate response, nor why the law’s chilling effect on free speech is not a valid concern. Calling this a “constitutional issue”, critics have argued that the matter needs to be decided by a larger constitutional bench of at least five judges.

“How is it that Kejriwal, Subramanian Swamy and Rahul Gandhi were on the same page, but the Supreme Court wasn’t?” asks Paranjoy Guha Thakurta, editor of Economic and Political Weekly. “There are criminal elements in the press, but this is a bigger issue. Defamation should be a civil offence and a judge can pass directions and make defaulters pay. But, in the case of criminal defamation, any magistrate can issue warrants for arrest.”

Thakurta recently co-authored a book on how press freedom is being stifled through court cases and the threat of litigation through legal notices. Speaking at a recent book launch, jurist Fali S. Nariman also said that while every person had the right to sue another through a civil suit, “there is little justification in criminalising a civil wrong; injury to reputation does not lead to a breach of peace or public disorder”.

Truth is said to be the only defence against a defamation charge. The Supreme Court has itself ruled that reportage requires only a “reasonable verification of facts”. This was upheld in a recent case where a news portal was awarded damages in a preliminary order after the National Stock Exchange sued it for defamation. The website had posted a report after trying to verify facts based on an anonymous tip, but the NSE had declined to comment.

In 17th-century England, perceived INSult often led to duels and breach of public peace, hence the penal provisions for criminal defamation. But India today, say critics, is hardly in a similar situation. They also point out that while truth is a complete and adequate defence in civil suits, in criminal defamation the onus is strangely on the accused to establish that the truth is for the public good.

The test of defamatory speech or writing is in proving that the author had some malice towards the person complaining of defamation. And it is indeed true that political rivals often make statements based on half-baked information for electoral gain. But the defamation law also comes in handy for penalising journalists or activists when their work brings them in conflict with people with reputations at stake.

Defamation then easily becomes a stick to beat free speech with, even when the right is exercised in pursuit of public interest. This, surely, is one law that is highly recommended for the long list of similarly redundant ones that the Modi government has promised to repeal.