What the zany Bollywood song Babaji Ki Booti from last year’s zombie comedy Go Goa Gone put out there in two lines (...Daaru, bandon ki gandi harkat....booti, uparwaale ki barkat...) pretty much summed up what the pot lobby has been saying all these years, and, indeed, what users and India’s babas have known for centuries. Yet, in India, from 1985 onwards, when cannabis cultivation and possession was criminalised under the Narcotics Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (NDPS) Act, retribution has been more the calling card when the ‘G’ word is mentioned.

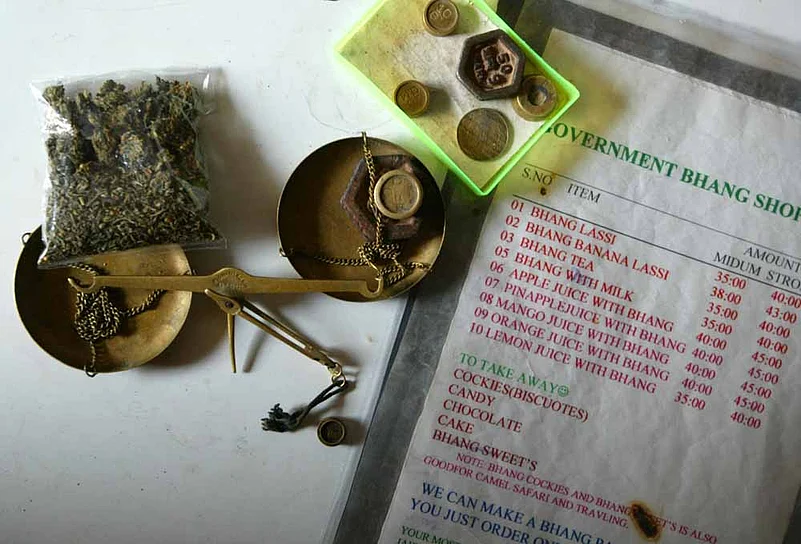

But the times are a changin’, at least out there in the wide, wide world. Colorado’s ‘joint’ effort to retail marijuana for recreational use seems to have opened the window of debate again. Should other states, countries follow suit? Ironically, it was under US pressure that India buckled to make cannabis illegal. Since then, India’s been caught in a cloud of smoke. Beyond the ‘all drugs are bad’ haze, most desi traditions continue unabated: stoned sadhus and yogis still invoke high spiritual standards, farmers across states grow marijuana (despite the raid fears) to make a little extra on the side, and ganja is openly used during festivals like Holi. But get caught with it and the ipc says possession or consumption of ganja can land you in jail for anything from six months to 10 years, depending on which side of the bed the honourable judge woke up. Voices of dissent against “this criminalisation”, however fragmented, have risen and fallen over the decades, but it’s all been too scattered to matter.

That could change. Calcutta-based filmmaker brothers Amlan and Anirban Datta, under the ‘BOM (Brothers of Malana) Charitable Trust’ umbrella, are in the process of creating a legal framework to cultivate, research and develop products from hemp. “The idea is to look beyond cannabis as just a means of ‘doping’, to how it can change a community’s prospects economically,” explains Amlan, who made a film last year (BOM—One Day Ahead of Democracy) about the travails visited upon the hill villagers of Malana in Himachal Pradesh, their only fault being a high-quality hash strain called Malana Cream. The second of the Datta duo, Anirban, adds, “The film won a national award, was embraced across party lines in Himachal, chief minister Virbhadra Singh even spoke in favour of legalising marijuana, but there has been no legal impact.” Kullu district SP Vinod K. Dhawan too strikes a conciliatory note, “What is dangerous is the hybrid varieties which we are cracking down on. But the native strains of the plant in Malana have multiple positive uses, especially in our cuisine.”

Meanwhile, last year The Bombay Hemp Company, or BOHECO, which calls itself India’s first industrial hemp company, opened shop in Mumbai, working with the government towards research, cultivation, manufacturing and retailing innovative hemp products. The company was invited early this month to speak at the National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad, on ‘Creating with Cannabis’.

But to put hemp to positive use, licensing is key. A lawyer friend is helping Amlan Datta get his licence in place. “The issue is the same as that of Section 377—decriminalisation. Marijuana is cultivated and sold in licensed shops in Orissa and UP, so why not elsewhere? The idea is to push an indigenous industry, led by a plant that has multiple benefits, including in construction, fashion, and revival of traditional foods like bhang parathas, pakoras etc. We’re going to try working around it in a permissible space. Let’s see where that takes us,” says the lawyer who prefers to be unnamed.

At the moment, though, the tide is still against ‘Go Green’ campaigners in India, mostly due to the deep middle-class prejudice against ‘potheads’, immediately positioning marijuana enthusiasts as social deviants and criminal elements. Such sentiment is also fed by the pharma lobby, feels Mumbai-based film critic Mihir Fadnavis. “It is scientifically proven that marijuana can help certain ailments, and is less harmful than smoking cigarettes or consuming alcohol. But it is in the pharma companies’ interests to oppose medical marijuana, else what will happen to their expensive drugs?” The benefits of revisiting the prohibition on cannabis are far too many to be ignored, he points out, not the least of which is “killing the narcotics trafficking business and the attendant corruption” by making it legal. For fellow Mumbai resident Svetlana, these legalities don’t irk, because “those who smoke it already know where to get it. It’s much easier to procure than 10 years ago. There is a definite need to separate cannabis from its association with other, harder drugs.”

One fact which may have the naysayers spewing smoke from their ears is that ganja is making a comeback of sorts on campuses. Perhaps it’s the ‘thrill’, as Svetlana says, “the unlawfulness of it, spotting a pedlar, scoring stuff”. Delhi-based Agneya Singh, who explores the rebellious young generation in his upcoming feature, M Cream, thinks it’s now more about a revival in countercultural movements, not unlike those of the 1960s and ’70s, when too weed was a key player. “Among the young, marijuana today is used more openly than we could’ve ever imagined. It’s everywhere. Legalising it could put some control over who’s buying it and from where,” he says. Unlawful or not, the bong connection lives on.