The news was,

He had been taken to the morgue

Last night—when the crescent moon had sunk

in the darkness of an early spring night

He desired to die

Wife was sleeping next to him—so was the child

There was love, and hope—which spirit, then,

Haunted him in the moonlight—why did he wake up?

Or, he may not have slept for ages—resting in the morgue now.

Is this the sleep he wished for?

Asked Bengali poet Jibanananda Das in his 1938 poem Aat Bochhor Ager Ekdin (A Day Eight Years Ago), speaking of a man who went to the peepal tree in the solitary, impenetrable dark after moonset, carrying ropes, “knowing that human beings don’t get to know the lives of birds and dragonflies.” He tells the story of a man who was not refused a woman’s love or the desires of a married life. Nor was he ever under financial duress. Is it this normalcy that left him lying in the morgue? The poet hints so.

“I do know

Women’s heart-love-child-home–aren’t everything;

Nor wealth, achievement, or affluence–

There is an imperiled wonder

Playing out

In our blood;

It tires

Wears us out;

That exhaustion is absent

In the morgue;

He lies therefore

on the table of the morgue

Flat on his back.

Why someone would take her or his own precious life, an act that cannot be undone, has plagued the thoughts of philosophers and writers for ages. Greek philosopher Empedocles of the fifth century BCE is said to have jumped into the volcano of Mount Etna, considering death as a transformation. In 18th-century German writer Goethe’s novel, The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774), the protagonist, a sensitive young artist, shoots himself in the head after realising his own death is the only way he could free himself from the love triangle he finds himself trapped in.

“I don’t think two people could have been happier than we have been,” Virginia Woolf ended her suicide note, crediting all her happiness to her husband Leonard. She was sensing the onset of another episode of mental illness, which she feared would be too much for her and her husband to bear. It was her third suicide attempt. “I can’t fight any longer,” she wrote, her letter replete with guilt of her illness spoiling his work.

While it was generally understood that people end their own life when it becomes unbearably hopeless, many nations considered it a criminal act, perhaps because it interfered with God’s hands in life and death. A failed attempt, therefore, not only meant social stigma but also legal harassment. And a barrier against seeking help whilst contemplating suicide.

Does suicide defy the almighty? It is a refusal to play a game whose rules have been set by others? Is it a refusal to live a life of dependency on others? Or, is it an escape from responsibilities, a betrayal of the dependent/s, an act of selfishness?

Whether they are acts of defiance or surrender we may never know of any death by suicide. What if one tends to believe the ability to end one’s own life makes human beings superior to other creatures? How may the right to live exclude the right to not live?

A two-judge bench of the Bombay High Court had dealt with the question of the ‘right to die’ while declaring section 309 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) as unconstitutional in 1987.

“The freedom of speech and expression includes freedom not to speak and to remain silent. The freedom of association and movement likewise includes the freedom not to join any association or to move anywhere… If this is so, logically it must follow that right to live as recognised by Article 21 will include also a right not to live or not to be forced to live,” the bench said.

In 1994, a two-judge bench of the Supreme Court of India affirmed this understanding. “If a person has a right to live, the question is whether he has a right not to live,” the bench said, and added, “We state that the right to live of which Article 21 (of the Indian Constitution) speaks of can be said to bring in its trail the right not to live a forced life.”

The apex court judgment said IPC 309 was “a cruel and irrational provision”, which deserved to be “effaced from the statute book to humanise our penal laws.” The judges hoped that their decision would “advance not only the cause of humanisation,” but also of globalisation, “as by effacing Section 309, we would be attuning this part of our criminal law to the global wavelength.”

European societies had started taking a humane approach towards those whose bids to kill themselves failed—who lived, perhaps to endure greater sufferings—from the second half of the 18th century. Germany was the first country to decriminalise attempted suicides in 1751 and, after the French Revolution in 1789, most of the countries and Europe and North America followed suit. But not Britain. Failing in a suicide bid could, and did, land the survivor in police stations, courts, and jail. In all British colonies.

“It seems a monstrous procedure to inflict further suffering on even a single individual who has already found life so unbearable, his chances of happiness so slender, that he has been willing to face pain and death in order to cease living,” English writer Henry Romilly Fedden wrote in his 1938 book, Suicide: A Social and Historical Study.

It was one of the quotations that the 42nd report of the Law Commission of India used in 1971 while recommending the repeal of section 309 IPC, which provides for imprisonment up to one year and/or a fine for attempting suicide. That was ten years after Britain finally decriminalised attempted suicide.

The Congress government in India in 1971 did not accept the 42nd Law Commission’s report. The Janata Party government in 1978 brought a Bill to implement the recommendations. It got passed in the Rajya Sabha but the Lok Sabha dissolved before passing it and the Bill subsequently lapsed.

The debate remained alive, though, especially with two high court orders, one delivered by Justice Rajinder Sachar of a Delhi high court division bench in 1985 and the other by the Bombay high court judgment of 1987 mentioned earlier.

The Delhi High Court dubbed the section “an anachronism unworthy of a humane society like ours.” The judges were clearly miffed and disturbed with what happened with the accused—the young man was arrested on the day of his alleged bid to kill himself by consuming insecticide, the police filed the charge sheet against him after eight months, the trial started after another 10 months, and after the magistrate acquitted him, the police challenged it before the high court.

“The result is that a young boy driven to such frustration so as to seek one’s own life would have escaped human punishment if he had succeeded,” the bench said.

While it did not comment on the constitutional validity of the provision, the Bombay High Court did declare the section unconstitutional for violating Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. The Andhra High Court, however, upheld the provision in 1988.

All these discussions were considered when the apex court, in 1994, decriminalised attempted suicide. The high hopes that the judges placed on their judgment, however, were short-lived. For, soon after the judgment, Punjab residents Harbans Singh and his wife Gian Kaur, who were convicted under section 306 of the Indian Penal Code for abetting the suicide of their daughter-in-law, Kulwant Kaur, challenged the constitutional validity of the IPC section.

They argued that if the court accepts one’s ‘right to die’ as a constitutional right under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution, then abetment to suicide could not be a criminal act. “Any person abetting the commission of suicide by another is merely assisting in the enforcement of the fundamental right under Article 21,” reads the Supreme Court’s March 21, 1996, judgment about their argument.

After hearing the case, a five-judge constitution bench of the Supreme Court overruled the two-judge bench’s judgment in 1996 and declared section 309 IPC as constitutional. The bench did not go into the debate over whether suicide should be considered a crime or not, they set their focus on the scope of Article 14 and Article 21—if Section 309 IPC violated them. It did not, they concluded.

The court also rejected the argument on the ‘right to die.’ “‘Right to life’ is a natural right embodied in Article 21 but suicide is an unnatural termination or extinction of life and, therefore, incompatible and inconsistent with the concept of right to life,” the bench said.

Soon after, the 156th report of the Law Commission, submitted in August 1997, recommended the retention of section 309 IPC. It came up with a new argument. “Certain developments such as rise in narcotic drug-trafficking offences, terrorism in different parts of the country, the phenomenon of human bombs, etc. have led to a rethinking on the need to keep attempt to commit suicide an offence,” it said.

It may sound a little strange, or even ridiculous, given that there has been no dearth of penal provisions to deal with those serious crimes. An apparently mild provision—which the Supreme Court said it was—would have surely come of no use.

In any case, it took another nine years for the Law Commission to recommend the repeal of the section, which happened in 2008, with the commission’s 210th report, on which the Union government sought responses from the states. In December 2014, the government told Parliament that it had been decided to repeal IPC 309.

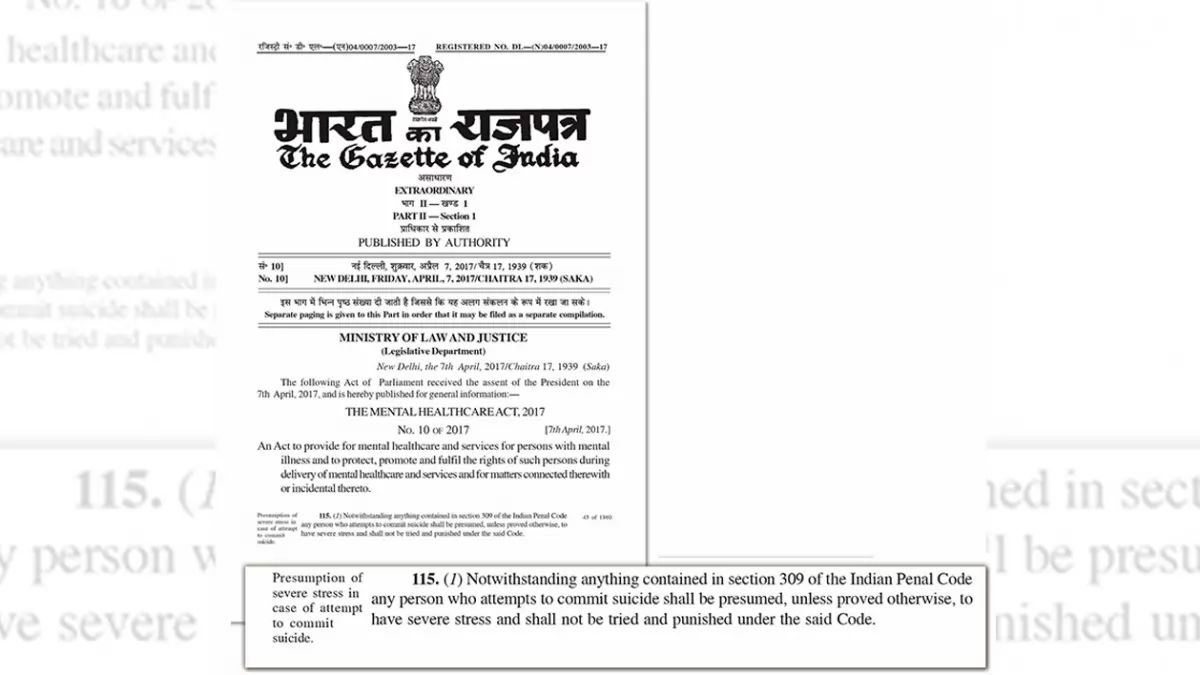

That is yet to formally happen, even though Section 115 (1) of the Mental Healthcare Act, 2017, exempts suicide attempt survivors from the ambit of section 309 IPC, presuming, unless proven otherwise, that they “have severe stress.”

(This appeared in the print as 'Right To Die')