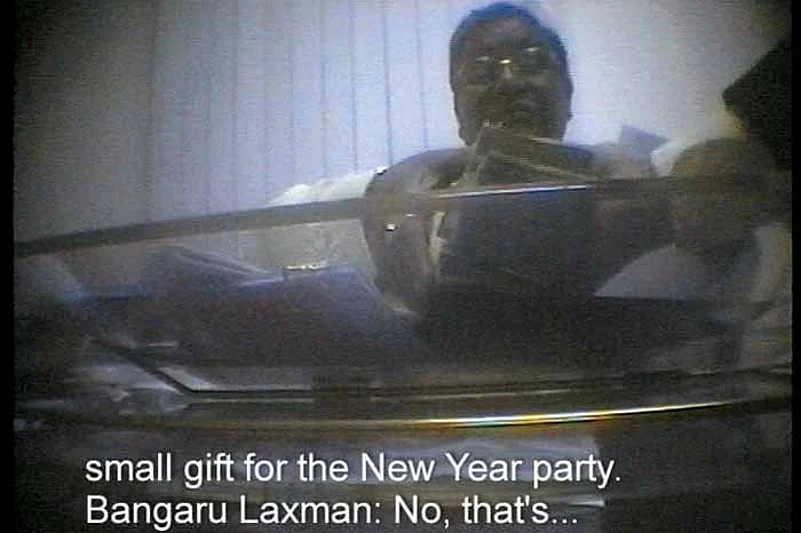

Like the rest of the nation, I too sat before the idiot box and watched former BJP national president Bangaru Laxman being taken to prison last week. Wasn’t it just the other day when I was actually sitting before him and handing over those bundles of one lakh rupees in cash? He had offered to help clinch a defence deal in what has come to be known as Operation Westend, little suspecting that it was a sting operation.

Bangaru’s conviction and imprisonment left me with mixed feelings though. I did feel vindicated at one level, this being the season of defence scams and scandals. But I was also disturbed by the question of the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) fast-tracking the case against the BJP’s Dalit icon and not against equally or even more influential people like Jaya Jaitly, R.K. Gupta, R.K. Jain and others, all caught by me on camera, accepting bribes just like Bangaru Laxman did.

The CBI was clearly in a hurry to bring the case against Bangaru to a closure. In September last year, they were desperate enough to request me to fly back from Goa for a final deposition in court. They even offered to reimburse my plane fare but afterwards, the agency denied making any such offer. I wish the CBI had shown as much urgency in pursuing the other politicians, businessmen and brokers. Why the agency has dragged its feet in the other cases, only the CBI can say.

***

It all began on a train journey, on the Deccan Queen in fact. I was on my way back to Mumbai from Pune. A casual chat with a co-passenger—who turned out to be a supplier to army canteens—led us to plan the Westend sting operation for the portal, Tehelka, where I was then a special correspondent. The organisation, after some initial hesitation, backed and funded the operation.

Photograph by Tribhuvan Tiwari

We created fake brochures for a fake firm in London, ostensibly dealing in equipment for the armed forces. Visiting cards were printed and I began by meeting the juniormost babus in the chain and worked up the ladder to try and sell hand-held thermal imagers. Anil Malviya, the canteen stores department (CSD) contractor who first gave me the idea, was also the one who paid the first bribe, just two thousand rupees, to a junior official of the defence ministry. He had brought an entire list of equipment that the army was looking for.

We met scores of officials, in the ministry and from the army. We met wheeler-dealers and minor politicians. We called on fund-raisers of the BJP and the Samata Party and taped our conversations and used spy cams to record our meetings. Although I personally recorded 99 of the 105 tapes, nobody suspected anything. All of them told us that no defence deal could be clinched without wine, women and cash.

I met Bangaru Laxman and Jaya Jaitly because defence personnel made it clear that procurement over Rs 50 crore needed clearance by the cabinet. Jaitly was a prominent Samata Party leader and close to the then defence minister, George Fernandes. And Laxman, of course, was the BJP president. I was advised to meet both and solicit their help.

I had earlier met the BJP fund-raiser, R.K. Gupta, who was close to the RSS. He had also accepted cash and promised to help. I had gifted a gold chain worth Rs 10,000 then to Satyamurthy, who was in charge of giving appointments at Bangaru’s house. The reference to Gupta and the gold chain convinced Satyamurthy of my credentials and an appointment was finally fixed with the BJP president.

When I reached his house, Satyamurthy, who brokered the deal, insisted on Rs 10 lakh as initial payment to Bangaru. I offered to pay Rs 1 lakh in cash immediately and the rest later, saying truthfully that I did not have Rs 10 lakh on me. The entire sting operation, I believe, cost Tehelka around Rs 11 lakh. The money would be handed over to me by Aniruddha Bahal, then the editor (investigations) of the portal, and I was expected to actually pay the money and record the encounters.

Catching Bangaru on camera turned out to be easier than I expected. I was using a briefcase device, which had a horizontal lens and a vertical one. Since he was seated and the briefcase was placed on the table in front of me, the horizontal lens was actually turned towards me as I took out the cash.

So, while handing over the cash to him, I had to turn the briefcase the other way, towards him. I was apprehensive that he would notice the awkward movement but he did not react. To hide my nervousness, I asked whether he wanted the remaining cash in Indian currency or in US dollars. He asked for dollar bills.

It turned out to be more difficult to catch Jaya Jaitly on camera. Madam, I was told, would not allow any briefcase inside the defence minister’s house. But she had no problem with cash, of course. She possibly knew about spy cams and the briefcase device. I was told that an Indian cricketer may have shown her how the briefcase-camera worked.

I therefore arranged for a spy cam on a tie-pin. The trouble was that the battery was tucked inside my underwear and the remote was in my pocket. And when I switched it on, the battery would start vibrating inside my underwear. The few minutes I spent in her presence were among the most uncomfortable moments I have ever had.

I was spared the trouble of recording the sexual escapade of Brigadier Iqbal Singh with a high society callgirl, arranged by a former Indian cricketer. She turned out to be a good sport and offered to record her romp with the brigadier.

In court, both Jaitly and Bangaru first claimed that the tapes were fake; their images had been superimposed; pictures were morphed; their voices did not match; that the tapes were doctored. Once forensic tests established that the tapes were genuine and their voice was on them, they pleaded that they were honourable persons and collected donations for the party. They fabricated receipts as an afterthought and claimed they had given receipts for what they received. They also claimed that since Westend was a fictitious firm and as I was posing as a representative of this non-existent firm, there was no real deal and, therefore, the charges against them were not tenable and should be dropped.

In Bangaru’s case, the court held that the tapes showed he had taken me to be a serious vendor, had accepted real cash and had promised help in securing defence deals. And that was sufficient to convict him.

***

My cover as the representative of the fictitious London-based firm had been blown even before the tapes were released. I had rushed to Kerala to attend to my ailing father. But there was no mobile connectivity in Kerala then and my increasingly suspicious contacts were constantly calling me for the rest of the amount. On receiving no response, they approached the service provider, secured the office address and a few casual questions there led them to my rented flat.

Some of those contacts had been suspicious from the beginning. One of them insisted on learning where I lived so that he could drop by for a drink. Luckily, I knew of an eccentric recluse who lived alone in Janakpuri with as many as 20 dogs. I gave out his address and said that I lived alone in a part of that house. He visited the house only once but left quickly, thanks to the ferocious dogs.

In retrospect, I now believe Operation Westend has been a wasted exercise. Nothing has changed. If anything, things have become much worse. Corruption in procurement for the armed forces has become endemic and more money is changing hands than ever before.

The Tatra trucks, which is in the news following army chief V.K. Singh’s allegation that he was offered a bribe of Rs 14 crore for clearing the purchase of 600 of the trucks, figured in many of our recorded conversations in 2001. Officials openly spoke of deficiencies in the truck and how deals were being struck and how much money was being paid. Ravi Rishi’s name also figured in several of those conversations.

The CBI has been in possession of those 105 tapes for the past 11 years. I wonder why the country’s premier investigating agency ignored the evidence on Tatra all these years. Is it possible that nobody heard the tapes or failed to read the transcripts?

As a prize prosecution witness, I have been forced to spend months together in various cantonments and depose before courts of inquiry. When you spend three months at a stretch in the officers’ mess in a cantonment, you hear stories. Almost every evening, someone or the other would be talking of the corruption involved in defence procurements. Sub-standard equipment, rations, medicines, arms, ammunition—the list was endless. A few senior officers actually cried and said they felt ashamed and helpless. That the jawans were being taken for a ride by some black sheep in the army and the politicians. But there was little they could do.

The six serving army officers, and four retired ones, who were convicted for their crimes, were surprisingly stoical. Calm and resigned, they would sometimes chat with me and ask, with a wry smile, whether the sting would stop at ruining only their lives and careers or whether it would also expose the politicians with their dhotis down.

The CBI had registered 12 cases in all on the basis of the tapes. The case against Bangaru Laxman was just one of them. The agency had also filed cases against us in Tehelka for violating the Official Secrets Act. They also filed cases against two officials of the Central Secretariat Service, Neeraj Kumar and Thomas Mathew. Both of them were suspended and charged, possibly because they had interacted with me. But they had played no role in the sting.

I am not really surprised because the CBI also linked me with Sonia Gandhi and her secretary Vincent George (remember, it was the NDA government in power then), two people I have never met or spoken to.

***

I have not done a single sting operation since 2001. I even discourage others from undertaking any sting, citing my own experience. The day after the Tehelka tapes were released, on March 13, 2001, my landlord in Delhi’s Greater Kailash locality threw us out of his house. Police and Intelligence Bureau sleuths had turned up the heat and he could not bear it. My wife, who worked for a private firm, had to quit her job because it became impossible for her to continue, with police and the IB constantly arriving at her office to make inquiries. Sleuths from the IB even went to my village in Kerala and interrogated my father.

The Tehelka portal had by then been shut down (for two years). I have not held a permanent job since then due to my preoccupation with the cases. For eight months, I worked for the portal without any payment.

While the army provided hospitality and transport for deposing before courts of inquiry, the CBI paid me Rs 250 per day and Rs 25 extra for lunch. The parking fee at the courts in Delhi is Rs 50 and the rest was spent on food and transport. How was I expected to maintain my family?

A labourer in Delhi receives Rs 450 per day under the NREGA. But when I met the CBI director to plead for a reasonable amount so that I could give evidence as a witness, he asked me to get the money from Tehelka. The reply was the same when I spoke to V. Narayanasamy, the minister at the PMO.

The CBI director now, A.P. Singh, asked why I got involved in sting operations and advised me against doing such reports in future. I have now stopped going to the court to depose as witness. I cannot afford to do it any longer. Ironically, I cannot leave Delhi either because of the case against me. I cannot afford a lawyer and I am threatened with the prospect of a non-bailable warrant if I do not turn up to depose. It’s a Catch-22 situation from which there seems to be no escape.

(As told to Uttam Sengupta)