One can hardly ignore the buzz among Chinese Communist Party workers every time Wang Qishan is mentioned. You can’t really call the 67-year old politician “a rising star”, especially since he is due to retire in two years. But as head of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI)—that makes him the chief investigator of the massive anti-corruption campaign launched by President Xi Jinping—Wang is one of the most feared and respected figures in China today.

His expertise, however, is not criminal investigation. The former banker, who has also been the mayor of Beijing, is known in party circles as a very effective troubleshooter. Wang is ranked much below the others in the all-powerful seven-member standing committee of the CPC politburo, but his current job profile and the mandate to investigate a large number of party leaders and officials has now made him a virtual No. 2 to Xi. The growing number of profiles Western media has carried on Wang in recent months is one such reflection of the man’s rising political stock. “Since he has no children, he is the ideal man for the job,” says a party worker.

It is interesting, therefore, that as the world continues to deal with and debate the impact of Beijing’s decision to devalue the renminbi (popularly called the yuan) and its impact on the Chinese and global economy, for many in China, the focus remains on how the anti-corruption drive pans out in the coming days.

This is not to suggest that the Chinese are not affected by the recent crash in their stockmarket—a move that also sent stocks all over the world tumbling. Many have seen their investment erode in the bloodbath in the Chinese stockmarkets but they are also keen to see how fast and well the country manages to stabilise the economy.

International experts, though, continue to be sceptical about a fast recovery for the Chinese economy, despite the fact that the stockmarkets globally have already begun to rise and stabilise, sending positive repercussions in the world economy. “As the main driver of global growth since the financial crisis,” says professor of international economics and trade at Cornell University, Eswar Prasad, “fluctuations in China’s growth have large spillover effects, especially in commodities markets.”

However, the slow growth in the Chinese economy, termed the “new normal” by the leadership after three decades of 10 per cent plus unprecedented growth, does not seem to worry Chinese experts. “China’s 7 per cent economic growth in the first quarter is within market expectations,” says Qiao Xinsheng, a Chinese expert in a signed opinion piece in the China Daily recently. China’s economic slowdown, he points out, is more a result of its “voluntary efforts to achieve sustainable growth and structural adjustment”.

Most party leaders and government officials in China agree with this view and see the decision to devalue the RMB as part of the much-needed structural adjustment in the country’s economy as they try to explain the intrinsic linkage between the anti-corruption drive and steps to stabilise the economy and make it more sustainable and healthy.

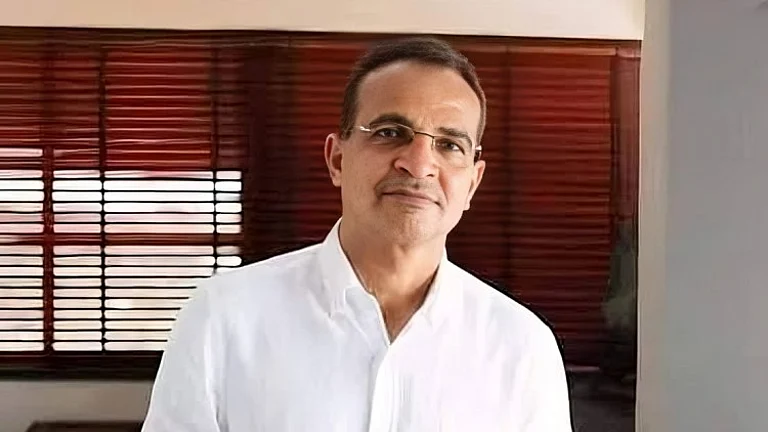

Wang Qishan A man to be feared

The anti-corruption campaign, typical of the Chinese penchant for exotic titles, is named ‘Tigers and Flies’—where all the 205 full members of the party’s central committee and 171 ‘alternate’ members (those waiting to get into the central committee) are the ‘tigers’ while those below are the ‘flies’. Though the drive had begun some years back, it has intensified and been cast much wider under Xi.

According to the Chinese government, about 99 per cent of the corruption cases exposed in recent years are related to infrastructure construction and investment. Some 70 per cent of them involve trading power-for-money deals in approval of land leasing and house demolitions. “It is now an indisputable fact that under the government-led investment model, areas with greater governance presence have been inundated with corruption,” says Qiao Xinseng, dean of the anti-corruption research school of China’s Zhongnan University of Economics and Law.

A number of important leaders have already been charged and convicted for corruption. These include former president Hu Jintao’s personal aide, Ling Jihua; former Chongqing party chief Bo Xilai and his wife; the former vice-chairman of China’s top military body, Xu Caihou; and retired standing committee member of the politburo, Zhou Yongkang.

Chinese sources say that many more ‘tigers’ are now being questioned by the party investigators, and their names and the exact number will be known only in the coming days. As of now there seems to be a popular support for the anti-corruption drive launched by the Chinese leadership to weed out and punish guilty leaders and officials.

So what is the connection between the anti-corruption drive and the structural reforms needed in the Chinese economy?

According to Chinese officials, the need to bring about a change in the country’s economic pattern to make it more sustainable was something Chinese leaders realised some years back. But the structural adjustments would also mean breaking away from the existing pattern, and this is where a number of senior leaders and their well-entrenched network of followers put up stiff resistance. Since most of them held key positions and benefited substantially from allowing the current system to fester, there was a need to use the anti-corruption laws to break their stronghold on the economy and ‘patron-protege’ network called ‘Mishu clusters’.

One of the most important cluster Xi aims to dismantle is one ex-president Jiang Zemin put in place. This not only helps Xi consolidate his own position in the party but also allows him to bring about the necessary reforms to the Chinese economy. “It will not be easy to break these networks,” says Rana Mitter, head of Oxford University’s China Centre. “They have been built up over years and represent strong economic and political interests.” He predicts “people will fight harder, because in China, the consequences may not be so much retirement as arrest and conviction.”

An important party plenum is scheduled for October this year, which will be attended by all the important Chinese leaders. Though the agenda is to finalise the five-year plan, it will also give a clear indication on how Xi plans to carry out his economic reforms programme.