In a quiet field less than an hour’s drive from Haridwar, Uttarakhand, Dr Rajesh Jain is at his lab overseeing the collection, filtration, condensation and ultimate conversion of cow’s urine into Shuddhi—a new brand of floor cleaner. This cleaner, Dr Jain hopes, will be lapped up by all the country’s honest-to-god-I’m-sick-of-chemical-disinfectant hausfrau. “It’s 10 per cent cow’s urine, 90 per cent neem, eucalyptus and some other herbs from nature’s lap that I can’t name just yet,” he says. The unit, functioning from a cow shelter, can churn out 30,000 bottles of the stuff daily. Competition is heating up, apparently, as many others race to launch their own cow’s urine-based home cleaners.

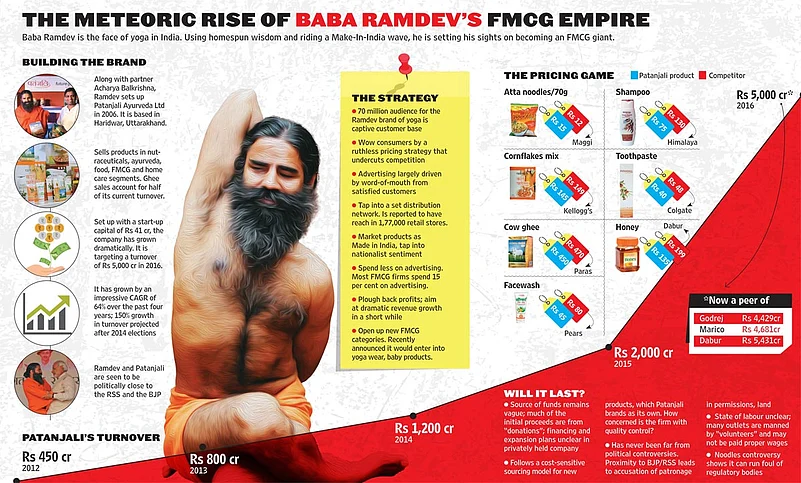

Now if there’s one man to thank for this, umm, phenomenon, it’s Baba Ramdev and his yoga-ayurveda-swadeshi empire, Patanjali Ayurved. Jain is a researcher at what’s become India’s fastest-growing fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) company. Ramdev’s firm is the surprise entrant to the corporate A-list and is the talk of the town today. He’s running India’s biggest swadeshi business empire—openly in sync with the aspirations of the ruling BJP, PM Narendra Modi, and the powerful persuaders behind Delhi’s throne, the RSS. And he’s winging it without bringing input costs or profit margins to the table, though Patanjali Herbal Tea, quite literally, is always on the menu.

To be sure, it seems that Patanjali Ayurved’s dramatic rise has happened almost overnight, taking even Bharat by surprise. The same cannot be said of Baba Ramdev’s journey though. He’s had his ups and downs, but has never been far from the action. Starting off as the yogic televangelist who controls Aastha TV channel, he became the yoga shivir guide whom the overweight, the inert, or simply the sick, have been swearing by since 2005. From the “bring black money back” activist of 2011, to the anti- corruption crusader of 2012, to the saffron-is-cool media savvy Congress-basher of 2013 and the desh-premi campaigner for PM Modi in 2014, Baba Ramdev’s multiple evolutions are a wonder in itself.

Baba brings something vital to Patanjali, but that something is of a more ephemeral nature—charm. His even-more-earthy partner, Acharya Balkrishna, actually runs the Patanjali business show (and reportedly controls maximum shareholding in the company). The Acharya, while he’s happy to be credited as the “strategist”, doesn’t appreciate the moniker “promoter”. But together, somehow, the pair has built a Rs 2,000 crore privately-owned dominion with interests in food (cattle feed, ghee, biscuits, noodles), cosmetics (aloe vera is a hit), household products (detergents), and Ayurvedic medicine (nutrients and ‘cures’ for diabetes, hypertension, cancer, hepatitis etc). Coming up next are shoes, yoga wear, baby nutrients....

To stay in context, Patanjali started out just six years ago, with a little over Rs 40 crore corpus. In 2016, they plan to touch Rs 5,000 crore. That’s a staggering 150 per cent growth from its current size. “I’m doing upkaar, granting a benefit, not running a business,” says Baba bluntly. But the fact that its growth has mirrored the BJP’s ascent to Delhi has not gone unnoticed. Questions have been raised on the dependence on a one-man brand, on the quality of its business processes.

Some of these concerns, of course, can be dismissed as griping from a nervous, entrenched competition. In the spectrum of companies competing over India’s $50 billion consumer goods market, there’s many a niche but none quite like Patanjali’s. Their key employees take no salaries, for starters (which includes Dr Jain, who has already spent over a year researching how cow’s urine can be put to better use). It is not really known how much Patanjali pays its labour force. An adoring, exceptionally loyal—some might even say fanatical—customer base, said to be 70 million-strong, swears by Patanjali products.

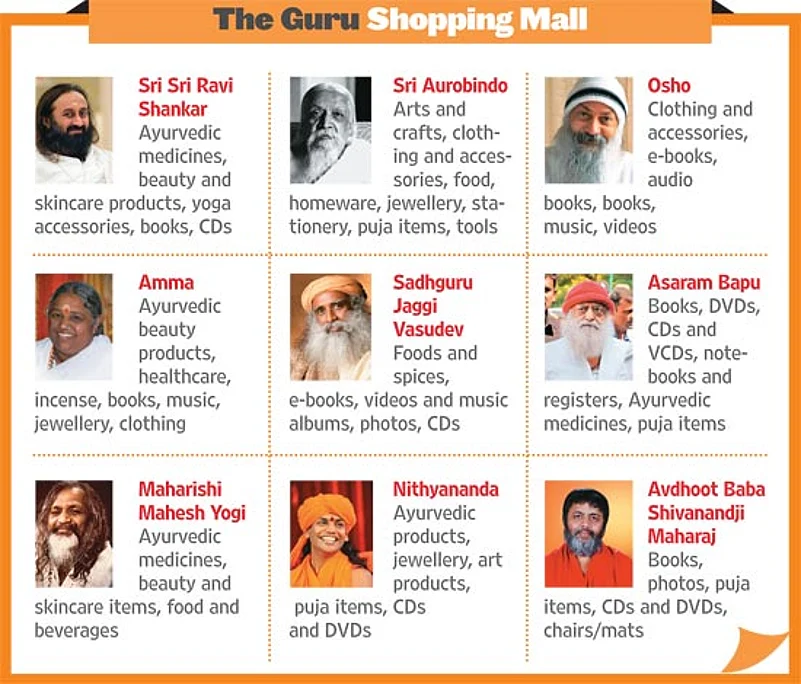

To compare with another well-known brand, this is like Tata’s legacy in manufactured steel which gets attached to the group, giving even its water purifiers or teas an air of reliability. In Patanjali’s case, the product’s reputation is the sum and substance of Baba Ramdev’s image. Unmistakably, the brand value exuding from the Baba is semi-religious. “Maybe you or I won’t go to yoga sessions with Ramdev on weekends but lots of Indians would. His is a distinct mix of Ayurveda with Hindu/Indian imagery that has crores of followers,” says ad guru Alyque Padamsee. “It’s the first time in India that an actual sant has branded goods...and he’s done exceedingly well.”

Graphic by Prashant Chaudhary

Baba Ramdev’s saffron robes are not just a mere prop—he is a bona fide yogi and sanyasi who has formally renounced material pleasures. It’s bewildering, then, that he girds up the loins of his mind to beat the corporate sector at its own game—low cost manufacturing of “quality” products. Patanjali’s top team, the Baba and Acharya, take great pride in how less their goods cost, a phenomenon hard-nosed businessmen would call cost-competitiveness.

How exactly do Acharya Balkrishna and his mentor keep costs low? “They’re a very different type of company,” says Abneesh Roy, a Mumbai-based associate director at Edelweiss Securities, which recently published an upbeat report on Patanjali Ayurved. “Their employee expenses are far lower since most people working there come with a social cause in mind. They are also not so profit-focussed,” he says. Patanjali also has minimal advertising and marketing expenditure which, going by Roy’s report, allows discounts of 15-30 per cent compared with peers.

Roy’s report did not take into account the branding or promotion through Baba Ramdev’s Aastha channel. However, it did consider the huge following at his yoga camps—Edelweiss estimates a potential reach of 200 million without having to mainstream advertising expenditure, and relying largely on word-of-mouth. “They are simply not greedy,” says Devinder Sharma, an agriculture expert who has been in touch with Baba Ramdev since the latter struck a clarion call against corruption in 2010. “Also, we do hear from time to time of a Nike or an Adidas breaking labour laws or other regulations—why then, when it comes to Baba Ramdev and Patanjali, is everybody suspicious?” he asks.

For the poor who throng Patanjali’s little retail outlets for everything from herbal medicines and everyday goods such as tomato sauce or candied gooseberries, the Baba’s promise of a ‘cure’ for serious illnesses merely through yoga is the biggest magnet. It’s a phenomenon nobody in India has missed—every family has a member who uses Patanjali products, and not just that—swears by them. This offer of a cure—including for cancer—shows up India’s healthcare system for the weak mess it has become. It also shows the great trust and faith ordinary citizens place in Baba Ramdev himself.

Cleaned Floor cleaners being packed at the Haridwar plant

This sends multiple jitters down the medical establishment’s spine. “Under Indian law, no one can claim a cure for 54 diseases listed by law under the Drugs and Cosmetics Act,” says Dr K.K. Aggarwal, secretary-general, Indian Medical Association (IMA). Cancer is one of those diseases, as is diabetes. In 2011, IMA wrote to the government demanding “strict action” against Baba Ramdev for propagating that yoga can cure cancer, diabetes and heart disease. The Baba, however, insists Patanjali has “scientific proof” that their cures work for cancer as well as other ailments.

There’s little forthcoming from the two men at the top on exactly how much is gathered up as donation on an annual basis. The donation model was the mainstay of Ramdev’s mass yoga lessons during 2005- 10, but soon after, it began to take Patanjali’s Ayurveda interests much more seriously. “There was a time when moneyed people were involved in his yoga shivirs. They paid a fee to attend and that became the source of financing. Then came the anti-black money movement, which the government at the time tried to suppress,” says RSS ideologue K.N. Govindacharya. He’s referring to a particularly hair-raising episode in June 2011 when the Congress-led UPA government staged a raid on Baba Ramdev and his supporters. Since then, Patanjali has been building muscles, and “Ramdev has made fewer offhand comments”, says Govindacharya. Ramdev now believes money—or ‘arth’—is critical. “If you don’t have money, you can achieve nothing, and nobody comes to your aid,” he says.

Ramdev’s political friends, nevertheless, straddle all walks of life, every political colour, just like his mass-appeal yoga. That’s because of his own, unique charisma as well. He may be considered close to PM Modi, but Patanjali’s sales won’t dip in Bihar just because the BJP lost elections there. Yoga, ayurveda and the symbolism of Hindu culture, combined with its links to swadeshi and nationalism, are a heady, tough-to-ignore mix forged by Patanjali.

In this model, still being perfected by Baba Ramdev and Acharya Balkrishna, healthy food—say wheat noodles—are also good for desh bhakti. And nobody stops to wonder if there really is anything swadeshi to noodles? As Baba says, “Hamne noodles ka bharatiyakaran kar diya hai.” They have Bharat-ised noodles, and biscuits and tomato sauce. “How can our noodles be foreign when they have been made completely locally?” he asks.

Getting organised, without doubt, is Patanjali’s next challenge. The privately held concern is still opaque, though an effort to implement computerised planning is under way. “We will enter all healthy and non-harmful consumer goods categories,” says Acharya Balkrishna. At present, sourcing is relatively non-transparent: for instance, only after the FSSAI raised objections to the license displayed on noodle packets did it emerge that it was not being manufactured in-house, but through contractors.

At present, 90 per cent of Patanjali’s manufacturing is in-house, but this model will be tweaked to meet demand. Says Arvind Singhal, CEO, Technopak, a retail consultancy, “Somewhere, subliminally, it’s seen as lucrative to have an Indian soul in your business.” The only challenge ahead, he adds, is that organised players will have to be careful about claims they make for their wares.

Indian corporates are yet struggling to understand what’s hit them. A lot depends on how deep the ayurveda market is—though it’s definitely not bottomless. “The penetration of ayurvedic products is very low today and we feel that new players will help expand this market. So we look at new players as growth facilitators and not threats,” says Dabur India CFO Lalit Malik.

All said and done, Ramdev and Patanjali represent a semi-religious consciousness. Perhaps that’s why Ramdev is being deified. At the Haridwar HQs, Patanjali’s piece de resistance in architecture is a massive office-cum-residential headquarters. The centrepiece is occupied by Sadhbhavna Bhavan, a grand entrance hall inside which is a raised semicircular platform, atop four gauche pillars. When the time is right, Baba Ramdev takes his place on the single sofa-cum-throne placed in the middle of this platform. It’s secured by a small iron grill gate, and Ramdev addresses his followers from this little turret. No doubt, whatever he says, it will be a grand affair.

***

Ramdev’s Many Controversies: A Decade-Long Timeline

Mar 2005—113 employees of Ramdev’s Divya Yoga Mandir Trust agitate for minimum wage and employee rights. The matter was resolved after discussion but some workers dismissed after alleged sabotage.

Jan 2006—CPI(M) leader Brinda Karat claims the Patanjali Trust’s medicines use human bone powder. Presence of animal material in medicines confirmed initially; later tests gave an all-clear.

Dec 2006—Received a cease-and-desist order from the Indian Union health ministry for suggesting that his yoga could cure AIDS and that sex education in schools should be replaced by yoga education

Sep 2009—Gifted a Scottish isle called the Little Cumbrae island off the fishing town of Largs, worth £2 million

2009/ 2011—Opposed the Delhi High Court’s verdict for decriminalising homosexuality. Said it was a “disease” which could be “cured” by yoga in just six months.

Jun 2011—Posed as an injured women in a white salwar-suit to escape from the Delhi police during his protest against black money at the Ramlila Maidan

Jun 2011 Activities of Baba’s non-profit in Virginia, US, come under police scanner for indulging in commercial activities such as selling healthcare and food products online—which was hence deemed illegal

Jun/Nov 2011 Faced charges of 81 cases of violation of the Zamindari Abolition and Land Reforms Act and the Indian Stamps Act by UPA govt

Nov 2012 Director-General of Central Excise Intelligence blames Ramdev’s trust for running a club under the garb of a trust

Feb 2013 Moves Himachal HC over state govt action to take back possession of a chunk of prime land allotted to Ramdev’s trust in 2010 by the then BJP government

Sept 2013 Detained for 8 hours at London airport. Reasons unknown.

Oct 2013 Ramdev’s firms raided by excise officials in relation to unpaid amounts of excise duty on cosmetic products manufactured by the company. The total liability for the firm was ascertained at about Rs 20-25 crore.

Apr 2014 Caught on tape asking BJP candidate Mahant Chand Nath to not talk about black money in a conference when the media was around. The comment came after Chand Nath told him, “We are facing a lot of problems in getting money. We can’t bring money into the constituency.”

Apr 2014 FIR lodged against Ramdev in Jaipur for alleged remarks against Dalits. Ramdev later apologises, says he was misunderstood.

Dec 2014 Calls for social boycott of film PK, saying such films “denigrate Hindu culture”

May 2015 Ramdev’s brother Ram Bharat is arrested when Daljeet Singh, a truck union leader at the Patanjali herbal food park in Haridwar, dies in a clash between workers and the administration

Aug 2015 Baba Ramdev argues that a law should be created to control the “Muslim population growth” in the country

Nov 2015 Attacks Shahrukh Khan for star’s “anti-national remarks” on intolerance

Nov 2015 Claims he was denied the Nobel Prize for being black

Nov 2015 FSSAI chief says Ramdev’s noodle brand does not have clearance; Patanjali says it is above board, will respond to notice

By Pragya Singh with Arushi Bedi and Srishti Gupta