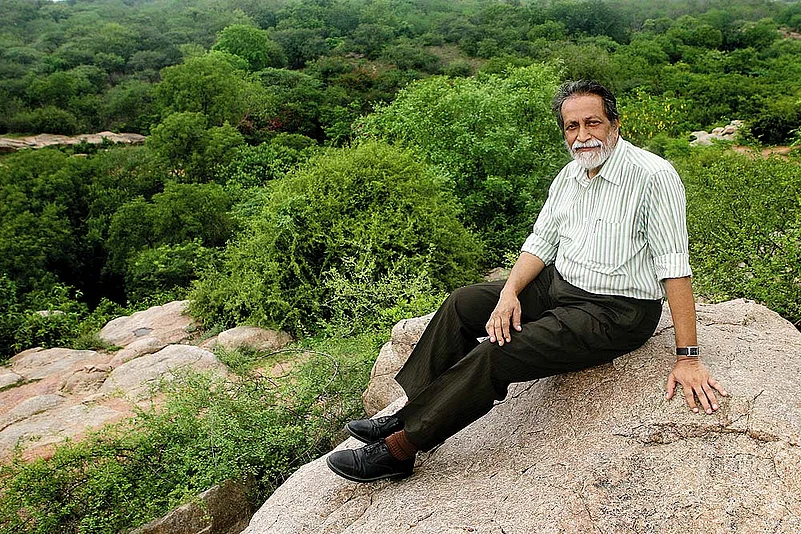

In 2008, economist Prabhat Patnaik was on a high-power UN task force on reforming global finance. Eight years later, as Greece’s crisis worsens, he speaks to Pragya Singh about the confrontation between globalised capital and democracy and lessons for India from the state of its rural economy. He also trounces austerity as an antidote to slowdown. Excerpts:

Are there lessons for India in this unfolding Greek tragedy?

In Greece there is a direct confrontation between the democratic opinion of people and the interests of finance. In that sense their crisis is a pointer to the essence of our times: Globalised capital moves from country to country. [But] what if the people of a country want a particular set of policies or a certain trajectory of development which finance doesn’t like? In this case finance would flee that country; make it bankrupt. This basic conflict between globalised finance and democratic assertions is what Greece symbolizes today. Every country is facing this dilemma—it’s just that attention is now on Greece.

How can Greece come out of its current crisis?

It is true that even inside Greece, demand could have been curtailed; not necessarily of the ordinary poor but of the rich who, as we know, don’t pay taxes and so on. Now Syriza [ruling Greek alliance] is actually saying, look, give us an opportunity. They say they will make adjustments, come down on all tax evasions. They want to reduce domestic absorption, but not by cutting pensions but by taxing the well-off. Syriza has been voted in because it’s against austerity—they cannot possibly accept austerity for old, vulnerable, marginalized segments, but they can, for criminal types or the wealthy. Also, Greek debt has built up over time so they want adjustments over time; some restructuring, debt relief too.

Are the Greek not responsible for their crisis?

I think there is quite a lot of misunderstanding, if you like, on this aspect. There is a view, for instance, that the Greek crisis is because the Greeks don’t work, because they are lazy, they live beyond their means and from which they are going into debt. That is completely wrong because any such crisis, whenever you have it in the world economy, implies a reduction in aggregate demand. It obviously affects individual countries, some more than others. Nonetheless, it makes itself felt at the level of the country. The point is, suddenly you find your exchange reserves have gone down because, say, tourists don’t come, because there is a recession and so on. Then what do you do? Do you start cutting back on all your services? Because, you see, if every country did that, then the crisis would become even worse.

Don’t they need a large write-off?

But, you know, the ongoing negotiations are not about debt write-offs.

You mean the negotiations focus on austerity?

That’s right, exactly. You see, it is not irresponsible, profligate, over-spending Greeks versus thrifty Europeans at whose expense they borrowed and consumed. Rather, Greece, caught in a particular situation, wants to make an adjustment in a way differently from what the creditors are insisting. It is here that the conflict between finance and democracy is taking place.

Greece went for a referendum over the IMF-EU-ECB terms. Can we try this in India? Here, even reformists now characterize reform as ‘difficult’ and ‘tough’ while parties like AAP do referendums…

I feel the referendum is a very smart idea of Syriza’s. Now there is a difference between an AAP getting hold of popular opinion and the Greek referendum. Syriza put out itself that it is for a ‘no’ vote. So, suppose the referendum had gone against them, the Greek government would have been forced to resign. AAP says, ‘We have no opinion. You tell us what we do’. Whereas Syriza says, ‘We have a position. You decide whether we are right or wrong.’ These are very different things.

What if we had national referendums on, say, the land bill? What do you think would happen?

[Laughs] The land bill would be thrown out by an overwhelming majority. Even before the Parliamentary committee, other than the industry chambers, everybody opposed it. I wish we had a referendum on this.… Just because BJP has majority in Lok Sabha they want to carry it through. They will bargain with Mamata Banerjee and Naveen Patnaik, but the first issue is, why do state governments fear clearing this bill? Because they know the overwhelming popular mood is against it. The land bill will be thrown out like anything in a referendum! In India we have never followed this route. If we did, it would be quite interesting. You’ll find that a lot of measures adopted in this country in the name of ‘reforms’ would not pass a referendum.

Isn’t the popular mood in Europe against bailing out Greece too?

It’s possible in Germany that may be the mood, but not in Southern Europe. In fact, people in Southern Europe will be looking very keenly at what’s happening in Greece because Demos may come to power tomorrow, in which case they might follow a very similar path. It is so in many other countries.

No—the government imposes reform. Even within UPA there were two very distinct groups. One was of [former PM] Manmohan-Chidambaram [former Finance Minister] and so on, who wanted these reforms. The other group had, let’s say, Sonia [Gandhi] and others—I don’t think they understood reforms very well. Chidambaram and the others were opposed to Right to Food, MGNREGA and so on. Even in Greece there are right-wing parties and other established parties who dominated Greek politics all this time. Both the right and the PASOK dominated politics there and supported austerity.

So Syriza has made reforms a global political economy issue?

Yes, it’s a very significant, historic moment. This is a revolt against traditional parties, who were all neo-liberal, all in sync with Germany and the Eurozone, and all for austerity. They all came to power, including PASOK, saying they are against austerity but fell in line. Syriza, till now, has remained in some senses loyal to its basic principles.

You said earlier the crisis is global, and one of its features is debt building over time. Why isn’t austerity the solution?

The Greek crisis is not a problem of Greece alone. It’s a reflection of the world crisis. It has to be seen in that context. Germany, for example, has a surplus, and is giving loans to Greeks because Greece has a deficit. If a surplus country like Germany could actually expand their demand, buy from Greece, it would alleviate considerably the problems not just of Greece but Southern Europe as a whole. The problem is that the surplus countries are under no compulsion to raise their demand. Look, what does it mean to be a surplus country? It means you hold claims upon others. The alternative is, instead of holding claims I buy your goods and distribute it to my population. Typically, instead, the surplus is seen as a source of power.

So a surplus country should make some kind of unpopular decision?

As a matter of fact [John Maynard] Keynes had suggested that the system should have some compulsion, not just on deficit countries to cut demand and so on. His idea was that there should be some compulsion on surplus countries also to undertake adjustment. That was never done.

What does this mean for policymakers in India?

Typically, in third world countries including India, economic policy is made by a coterie of ex-World Bank, ex-IMF people. Montek Singh Ahluwalia was like that. Arvind Subramanian was like that. Kaushik Basu went from here to the World Bank. Even our Niti Aayog’s [Arvind] Panagariya is ADB. It’s a small, globalised, financial bureaucracy that I think neo-liberalism insists upon. They all have identical positions in this bureaucracy, similar prescriptions and formulae—one of which is austerity.

What is wrong with this?

The very fact that there is a small globalised financial bureaucracy is fundamentally anti-democratic. People vote governments because they want some change in policies but the same coterie or their clones continue and so do their economic policies. Their strength lies in the fact that in the realm of financial free flows, if their policies are not adopted, then finance starts to flow out—what is happening in Greece. There is a fundamental conflict between the assertion of popular will, which is what democracy is all about, and economic decision-making by this coterie.

Is austerity comparable, with, say, sanctions?

Of course, austerity is coercive, but austerity is also stupid. The whole idea of recession is the lack of demand. If every country pursued austerity, the recession will turn into a depression. Immediately after the crisis in 2008, instead of austerity they pursued fiscal stimulus packages. That put some kind of flow [between economies]. Now, if austerity is insisted upon—with surplus countries under no compulsion to spend—overall demand across the world will decline. That’s why austerity is stupid—it’s opposed to the most basic macro-economics. That’s what [Joseph] Stiglitz and [Paul] Krugman and others have been saying for quite some time.

Are India’s subsidy cuts our way of being ‘austere’? Do they explain the shamefully low rural incomes and high deprivation in the socio-economic census?

Yes—and some things in the new socio-economic census are quite shocking. More than half of rural households are actually manual or casual-labour households. Can you imagine? They have no rights, no security of income, they are subject to the worst kind of drudgery of work because it is all manual work; they cannot be organized. It’s just a miserable state of existence. And you talk about being super power, of seven, eight per cent growth.

Seen in isolation, is the situation as bad? This survey has no recent comparable data.

Yes, the numbers are bad enough. But yesterday I did some calculations of my own from the Census and found that the proportion of rural labour households in total rural households has actually gone up compared with 1951. So the share of cultivators has actually fallen. A whole lot of people, who might have been independent peasants in the earlier period, are no longer so. They have been pushed into the ranks of agricultural labour.

Has trickle-down, as promised to us, and liberalisation failed?

I believe liberalization has come to a very serious impasse. The capitalism crisis has been going on for about eight years now. How come that there is no revival in sight? It’s because these policies are not going to result in any revival. State intervention to get individual economies out of crisis is not possible any longer unless you delink from globalization—this is what Greece will be forced to do, with capital controls, with trade controls, if this [negotiation] fails. In India neo-liberalism is under a cloud—how long can people continue without jobs and so on? Earlier it was felt that the crisis is “there”, we are safe, that’s no longer so.

Are there symptoms of this?

India’s export growth has gone down and if Mr. Jaitley reduces the deficit, with all the spending cuts already on—a whole range of welfare schemes are being slashed—you are going to find that India’s growth rate will go down much further. The Sensex is high but the poor, the rural people, as the socio-economic census shows, are not getting much benefit out of it.

Will there be political consequences in India?

Yes, because the middle class is benefiting from this growth, markets... If the economy slows further, I think, the middle class support for reform will deteriorate. Then political sustenance of neo-liberalism will become impossible. This is what happened in Latin America, and similarly in Greece. If the middle class begins to get hit the polity can no longer sustain neo-liberalism and I feel we will be approaching that in India. That’s when people will be open to other solutions and alternative economic explorations.

Do you see anything in the economy that portends a crisis?

The balance of payments will become worse in the current year, I think. One thing is for sure—the moment the US raises interest rates we are going to have a crisis. Because their latest figures show their recovery is not as expected, they are going to delay it. So, again, we can sustain ourselves. The question is how long can dollars flood the entire world? I don’t know what impact it is going to have, it’s an unprecedented situation.

Is the Indian government opaque about the economy because of such fears? We just released a “caste” census without caste data.

Actually, once they have done a caste census, there is no point in holding back the data. They should not have asked the question about caste—the state had no business to ask such questions. But there may be some point in actually seeing it now. Now it is just data, totally impersonal.

You are curious about the caste data...

I suppose I am curious—only because of our failures. By now you should have created the notion of an Indian citizen. Caste perhaps could have been [merely] a private thing, a ritual thing—if you say you cannot fully overcome something that has existed for millennia and so on. Fundamentally we have failed to create a polity of equal citizens. Given that failure, naturally, caste persists.

What is the relevance of economic issues for Indian politics today?

There have been occasions when the whole country mobilized around economic issues. Garibi Hatao was like that. To an extent, the 2009 victory was very substantially because of NREGS etc. That is the way it should be. People should respond to economic agendas. In the mid 1960s there was huge inflation, which had political fallout for the Congress. Similarly in the early 70s huge inflation would have got rid of Congress but [former PM] Indira Gandhi imposed emergency, perhaps anticipating this. I believe Janata Party’s collapse was also due to inflation after the second oil shock. I would even say that the mid-50s inflation was responsible for Congress losing at least two states, Orissa and Kerala. But of late, since there is no difference in the economic agendas of different political formations—NDA is doing what Chidambaram was doing and so on—people tend to differentiate in terms of caste equations etc, to a greater extent.

Is rolling back NREGA, food security, not a factor in voter choices?

It should be a factor. I hope the UPA makes it a factor. But the moment you do, you have to be prepared to follow it through—and not go for austerity. For Rahul [Gandhi], it’s one thing to say things when in opposition, and even to win an election on this basis. But then what do you do after elections? Either you tax the rich or run a fiscal deficit—both would be disliked by global financial capital. But when you pursue the same agenda as promised when you are in power, that’s where democracy manifests itself. We cannot cheat the people by saying one thing before elections and one thing after.

A shorter, edited version of this appears in print