A stick, a stone, it’s the end of the road, it’s the rest of a stump, it’s a little alone

“Om, gatey gatey, paragatey, parasamgatey Bodhi svaha,” I kept intoning under my breath, as the punishing uphill trudge through the unrelenting gorge of the Budhi Gandaki went on. The Bodhisattva vow had become something of a walking mantra for me, helping regulate my breath, keeping my grip sure and the balance of my backpack secure. Call it mindful walking. Sweating like a pig in the heat and humidity of the lower hills, I dug the mantra’s sentiment: small steps, steady steps, just a few more steps, till you reach your journey’s end. Sandwiched between the beautiful but overbearing canyon walls of the furious river before our camp at Deng, my spirit was struggling, my calves in agony.

Only three days in, the Manaslu Circuit trek was proving to be quite an eye opener. I’ve been on my fair share of treks, almost entirely in the Indian Himalaya, but this was the first instance of a trek that went as high as 5,100m, after beginning as low as 700m. In the Indian mountains, roads usually take you to starting points about twice as high as Soti Khola, where the Manaslu trail begins. No wonder then that the trek’s huge altitude gain—a whopping 15,000 feet—followed by a descent of about 10,500 feet, takes about two weeks to accomplish. Some guy with an iPhone had actually counted his steps, and put the distance covered at a respectable 223km till Dharapani, the nominal end point of the trek. That’s about all the way from Delhi to Agra. On the 4th day, the 14th day seemed far away.

And yet, why crib? In the four days till Deng, I’d passed through tropical forests in the lower valley, traversed a dramatic river route, and walked up through the spectacular gorges of Jagat and pine groves beyond the lonely village of Ekle Bhatti. Through it all, Antonio Carlos Jobim’s ‘Waters of March’ had kept me company, wafting through my brain like a running commentary.

The wood of the wind, a cliff, a fall, a scratch, a lump, it is nothing at all

“Bistare, bistare,” whispered a porter as he passed me with a huge load two days later. We were now in some profoundly different landscape. Slowly, slowly, his words meant in Nepali, and I couldn’t agree more. We had left the last of the lower gorges behind the previous day and the horizon had opened up, and craggy spurs rose from the meadows and ripe fields of barley flanking the Budhi Gandaki, past groves of pine and up into rocky pinnacles flecked with snow and ice. Think of it as something like the Yosemite Valley, but on a titanic scale. These were the lower flanks of the Kutang and Pangkar Himal, which formed a formidable 6,000m-high ridge barrier with Tibet.

We were now in the Nubri valley, as the upper area around the headwaters of the Budhi Gandaki was called. The Bhotiya people here are broadly of Tibetan descent, and ardent followers of Tibetan Buddhism. This manifested itself most commonly in the profusion of mani walls (walls made of rocks inscribed with Buddhist spells, mantras and depictions of Buddhist deities) and kani gateways that bookended the two ends of the villages here. We were walking to the village of Lho, famous for its monastery and views of Manaslu. Our hopes were high after missing out on views of the Ganesh and Shingiri Himals lower down the valley due to unsettled weather. As we approached the village of Lihi, the clouds parted for an instant to the southwest and the imposing ramparts of Himalchuli, a 7,800m giant, hove into view. But by the time our cameras were out, the clouds drew together, discretely hiding the mountain. We were surrounded by immensities that were determined to stay out of sight.

What we lost in mountain views, we made up with our immediate surroundings. Lihi and its sister village Sho had one main street, the Manaslu trail, with elegant houses of stone, shingle and slate fronting fields of barley on either side. The kani doorways, newly renovated and painted, depicted a bright cross-section of the Buddhist pantheon. Bodhisattvas, Taras and multiple depictions of Padmasambhava and Milarepa jostled for space with wrathful tantric deities and portraits of local lamas. Trekking in these border areas of Nepal, I couldn’t help but compare the sorry lot of the Bhotiyas of the Indian Himalaya since the 1962 war. Nepal’s border issues with China had been sorted a long time ago, and the Nepalese Bhotiyas were free to coninue the age-old salt trade with Tibet across nearby passes. Unlike the Indian Himalaya, you won’t find any abandoned villages, as the local economy of trade, sheep rearing and, increasingly, tourism, remains intact.

The foot, the ground, the flesh and the bone, the beat of the road, a slingshot’s stone

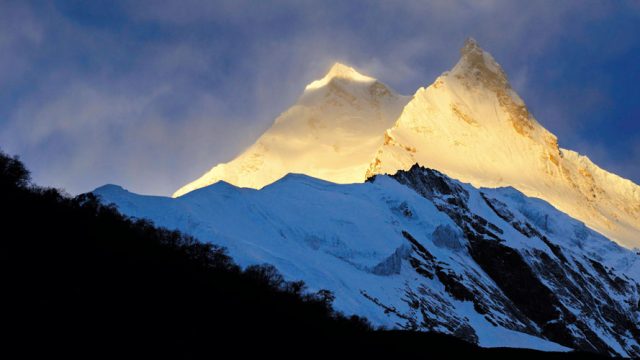

Bistare bistare, we reached Lho, but still no sign of any peaks. We had to wait till dawn the next day. It had rained quite heavily all night, and at the first crack of dawn, to the south, beyond a small hill which housed a pretty magnificent new monastery, Manaslu chose to reveal itself. Slowly, the purple clouds of night parted to reveal the dazzling, shining, giant; its unbelievable white granite cliffs and hanging glaciers gleaming in the light of the sun. Manaslu, with its prominent east pinnacle giving it the look of some horned deity, is the highest peak on a gigantic southern spur of the Great Himalayan Range. From our lodge in Lho, we could see two other peaks on the range, the 7,157m Manaslu North and its smaller neighbour, the 6,211m Naike Peak.

The weather refused to settle, and as we began our day’s walk up to Samagaon, the largest village in Nubri, Manaslu was already attracting fresh clouds. We descended to the ravine of a side stream, the Thusang Khola, and then it’s bistare bistare all over again, climbing up a steep trail beside the stream, through a pretty forest of birch and pine. I was mantra-chanting my way up when I heard a scattering sound of dislodged rocks to my right. I looked up and saw a herd of Himalayan tahr out for a stroll, unbelievably upright amidst the loose rubble of a landslide. I stared for a while, transfixed, as they slowly made their way across the ridge and out of sight.

While approaching Samagaon across the large meadow of Ramen Kharka, the first thing I could make out was the smoke rising from the village’s many chimneys. As we came closer, the long mani wall and prayer wheels surrounding the Sama gompa dominated the view. The stone and shingle houses had bales of hay and straw hanging from the roofs. Each house sported colourful prayer flags fluttering in the wind. Water drawn from the river and channeled from springs and snowmelt flowed in many rivulets around the hamlet, while tight little alleys wound around the houses, sporting a yak here, a dog there, and clambering children everywhere.

It’s the wind blowing free, it’s the end of the slope, it’s a beam, it’s a void, it’s a hunch, it’s a hope

Samagaon is at 3,520m, which makes it the perfect spot for a rest day to aid acclimatisation. Of course, an equally good reason is its proximity to Manaslu. It looms over the upper Nubri valley, its twin pinnacles more pronounced here, rising remote, yet near enough to frighten you on a full moon night. There’s a certain otherworldliness to the 8,000ers. They exist so high above that they don’t quite seem of the earth. What did seem of the earth, and therefore more terrifying, was the Manaslu glacier that swept down from the east pinnacle to end in the tangled, jumbled heap of an icefall, which, in turn, debouched into a giant glacier lake, Birendra Tal.

Impressions on the trail up towards the base camp: in a juniper and birch grove, a herd of bharal, oblivious to our presence, looked for leaves to chew on. The wind blowing keen and strong, scattering huge clouds over even bigger mountain faces. Now I know why the Tibetans consider the wind a manifestation of demons. Manaslu cloaked in a thick black cloud; its lower glacier a marvel. Every other minute came the roar of a serac crashing, as pulverised boulder-sized chunks of ice broke off and plummetted to the depths of the glacier lake some 1,500 feet below us. Birendra Tal is huge, but in this massive landscape, it’s just a landmark in a wider vista. To the west, across the Budhi Gandaki, the sharp fangs of the peak of Khayang were cloaked in cloud banners. We needed to reach 4,000m to acclimatise, which we did. I wanted to carry on further, but the cloud over Manaslu was roaring menacingly. So we retreated to Sama, rolling down the scree slopes as a squall followed us down.

A pass in the mountains, a horse and a mule, in the distance the shelves, rode three shadows of blue

I’ve always held true to a slightly unnerving Zen saying—it is impossible to fall off a mountain. Two days later, we set off in the darkness before dawn to cross the Larkye La, out of the Budhi Gandaki system and over into the Marsyandi Khola system. We’d stayed the night at the cramped and freezing staging post of Larkye Phedi, popularly known as Dharamsala. It had snowed all night, freezing the long communal dining hall, and threatened to smother my tent.

At 4:30am, the Milky Way was out as we stumbled along, our headlamps trying and failing to illuminate the vast Larkye glacier in front of us, and the long, long traverse of the ablation valley that lay ahead. My hands were frozen solid, despite insulated gloves, and it was getting harder to breathe as we crested the 5,000m mark. But the profusion of peaks crowding around helped me focus. To our right rose the ridges of Panbari Peak. To our left, lay the main bulk of the Larkye glacier, its white ice core camouflaged with a layer of dark soil and rock debris. Beyond it, the snow ridge of the Larkye Range. Behind us, in the distance rose the flying buttresses and plunging cliffs of the incredible Samdo Peak. Soon, the sun rose from behind Samdo and I thawed. Then I kept walking, following the orderly line of our group. Larkye La isn’t as high as most such passes in the Nepal Himalaya, but what it lacks for in altitude (Thorung La on the Annapurna Circuit is 5,416m), it makes up for in sheer length.

We reached the pass before midday. All I could think of, sitting under hundreds of fluttering prayer flags, was how to best keep the devilish wind out. Over the hump of the pass, a whole new valley system had opened up, with three large glaciers converging towards the hamlet of Bimthang, some 5,000 feet below us, its view blocked by the bulk of Larkye North Peak. The Cheo and Himlung Himal’s giant flanks stood out, but their heads were shrouded by thick black clouds that could only mean one thing—snow. And so began our race to the valley, trying to outrun the coming storm. You can’t fall off a mountain? This was as good a time as any to test that hypothesis. Scrambling down the steep ridge, negotiating wicked little patches of hard, slippery ice, we got to the top of the glacier nearest to the pass and then began a knee-shattering trudge along the side moraine. About an hour before Bimthang, the snowstorm caught us.

It began with a gentle drift of snowflakes, dancing little mote of white and grey against the gradually darkening day. Then these drifts began to turn into ever-thickening flurries. Even that was fine, until the wind picked up, and the flurry became a blizzard. The world turned black and then white as birch and juniper thickets started to close in. The snow drove horizontally into our faces. Every now and then, we’d have to stop our mad dash and dust off our jackets and bags. And yet more snow came. Everything was now an eerie twilit white, the plunging path went ever on over boulders and loose rocks, with nary a sign of Bimthang. At this point we were running blindly, beside a 200-foot wall of glacier moraine, mistaking every large boulder for a house, or a tea shop—a shelter from the storm.

After what seemed like an eternity, the claustrophobic thickets suddenly cleared and a wide, white meadowland opened up. Far away, a line of dark shapes appeared—Bimthang’s lodges. To my hysterical mind, the lodges were castle gates, and as we ran towards the ramparts, I imagined that howling ice giants were on our trail. My mantra had changed now, “Winter has come.”

The oak when it blooms, a fox in the brush, a knot in the wood, the song of a thrush

The next morning dawned passing fair—a clear blue sky, and the most amazing snowy mountain panorama that I’ve ever had the good fortune of seeing. To the north rose the forbidding ice cliffs of the Panbari, our descent route hidden in the disorienting snow. To its east, dominating the centre of the valley, sat great Nemjung, the first and the highest of the three peaks of the Himlung Himal.

Further east rose the gorgeous ice pinnacle of Kechakyu, partly hiding the upper fluted ridges of Gyaji Kang. To the south and east, a different view of great Manaslu—the broad breadloaf-like west face that rose abruptly to a snow plateau. The main peak could be barely seen, far back. Next to it, two savage rock and ice pinnacles thrust up like a frozen wave, the peaks of Phungi and Kampunge Himal. From the junction of the three Bimthang glaciers emerged a pretty river, the white Dudh Khola. Beside rhododendron groves heaving with spring blooms, and tall silver oaks, the riverbank talked of the waters of March, “It’s the promise of life, in your heart, in your heart.”

THE INFORMATION

Getting There

There are daily flights to Kathmandu from New Delhi from Jet Airways, Air India and Indigo. From Kathmandu, it’s a day’s drive

to Arughat Bazaar either by bus or by taxi. From Arughat Bazaar to Soti Khola, you can take a shared bus. On the way out, catch a shared jeep from Dharapani to Besishahar. Daily buses ply from Besishahar to Kathmandu.

The Trek

The Manaslu Circuit Trek is a long one, so you should have prior trekking experience. For purists, the trek begins at Arughat Bazaar in the Budhi Gandaki Valley and ends at Besishahar 20 days later in the Marsyandi Khola valley. However, the basic trek can be done in about 14 days, starting at Soti Khola in the Budhi Gandaki valley and ending at Dharapani on the Marsyandi valley. You can make the circuit longer by choosing shorter walking days and more acclimatisation days. You can choose to combine the Tsum Valley trek (approximately 7 days) with the circuit, or combine the Manaslu Circuit with the Annapurna Circuit trek via Dharapani. You will cross one pass, the Larkye La (5,160m) during the trek.

This is the route we took (distances are approximate):

Day 1 Kathmandu to Soti Khola (700m)

Day 2 Soti Khola to Khorlabesi (970m), 28km

Day 3 Khorlabesi to Jagat (1,340m), 17km

Day 4 Jagat to Deng (1,860m), 21km

Day 5 Deng to Namrung (2,630m), 20km

Day 6 Namrung to Lho (3,180m), 11km

Day 7 Lho to Samagaon (3,520m), 17km

Day 8 Samagaon, 25km (Sama to Manaslu BC and back)

Day 9 Samagaon to Samdo (3,875m), 17km

Day 10 Samdo to Larkye Phedi (Dharamsala) (4,460m), 13km

Day 11 Larkye Phedi to Bimthang (3,590m) via Larkye La (5,160m) 25km

Day 12 Bimthang to Gho (2,515m), 20km

Day 13 Gho to Dharapani (1,963m), 10km and drive to Besishahar (760m)

Day 14 Drive to Kathmandu

Ideally, you should factor in two rest days at Samagaon with day trips to Birendra Tal and the Manaslu Base Camp and Pungyen Gompa on the Pungyen Glacier. Like all Nepal treks, this is a teahouse trek, so there’s no need to carry camping equipment. The lodges are comfortable but basic. You can book them in advance by calling ahead. If you’re going with a trekking group then a porter is usually sent ahead to book rooms. The main expenses at the lodges is the food. One useful rule is to go by the Dal Bhaat Index. This staple diet starts at around NPR370 at Soti Khola and keeps rising till it tops out at around NPR700 at Larkye Phedi. It’s best to carry about NPR 30,000 to cover all expenses apart from lodging (all meals, hot water, wi-fi etc.). Apart from your trekking gear, be sure to carry a down jacket for use from Samagaon to Bimthang, microspikes for the iced-over tricky descent from Larkye La and

a powerbank. Mineral water is available everywhere for about NPR 150-200 a bottle, but a better bet is to mix chlorine or iodine tablets in normal water.

Note: High altitude insurance including emergency evacuation insurance by helicopter is compulsory for this trek.

Manaslu is a protected area so you will need a Manaslu Restricted Area Permit, a Manaslu Conservation Area Project permit, an Annapurna Conservation Area Project permit and a TIMS Card. Your trekking agency should arrange for the permits.

Currency ₹1=NPR1.57

How to do it

Almost all Kathmandu-based trekking agencies offer the Manaslu Circuit Trek. I used the services of the excellent South Col Expeditions (southcol.com). They charge $1,275 per person for the trek and this includes transport to and from Kathmandu, guide and porter fees, all permits, accommodation (twin sharing, excluding meals) during the trek and two nights (way in) and one night (way out) at a hotel in Kathmandu.