What began as an elitist phenomenon, restricted to the upper classes, naturally extended to the lower sections, often catalysed by political pressure. Reservations in education and jobs helped the backward classes and Dalits slowly, but steadily, become a part of the burgeoning middle class. "People today are looking to learn and work. If the economy and society provides these opportunities, people will seek them," feels Sunil Batra, an educationist with the Centre for Education, Action and Research.

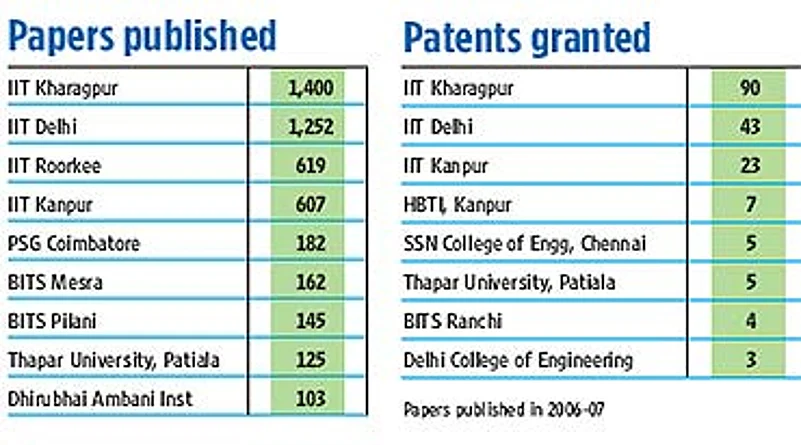

To understand the linkages between higher education and the middle class, one has to merely study two trends: the rise of the IITs (Indian Institutes of Technology) and the proliferation of private engineering colleges. Within 56 years of the first IIT in Kharagpur, its alumni are globally recognised as a premium brand. There are lakhs of IITians at large in the world. Many of them have made a name in the US, playing stellar roles in the new economy. As their social and economic stature grew, they also contributed to the growth of the middle class—directly (ploughing back some of the fruits, offering networks), and more importantly, presenting larger-than-life yet real models to be emulated.

During the ’90s, as the IITians shocked Silicon Valley with their entrepreneurial abilities, brilliance and strategic vision, as they took senior positions in dozens of Fortune 500 firms, as their startups sold at crazy valuations, they were realising India’s great middle-class dreams and tenets. First, says a recent book, they proved what the salaried middle class had always believed: "The only way #its children could get a fair chance to earn an honest living was to excel academically, do so well in their examinations that the ‘pull’ did not matter."

The US as the arena of professional triumph was itself a core part of the fantasy—not just as dream destination, but as the playground of pure competition in which to test individual excellence. As the book concludes: "The 1990s proved that the IIT system had delivered on nearly every promise it had made or implied. And there was no one left to doubt any more that ‘IIT’ was the biggest and the most powerful brand independent India had been able to create." (Of late, though, questions are being raised on the ability of these institutes to churn out quality.)

In any case, as the government failed to establish more IITs, ‘less’ endowed aspirants began to look at other avenues. Namely, private colleges. Beyond the zooming demand, socio-political factors too played a part in their mushrooming, specially in the south. For instance, in Karnataka, various chief ministers were forced to sanction more professional colleges to cater to caste lobbies—and protect their votebanks. In 2001, 45 new engineering colleges and six new medical ones were sanctioned in the state.

Powerful politicians realised there was money to be made in education and became either owners or trustees of many professional colleges. The answer to a question raised recently in the Karnataka assembly threw some light on the extent of this phenomenon. When legislator Prafulla Madhukar asked how many politicians owned the newly-sanctioned colleges, the reply was that 27 of the state-recognised colleges belonged to them! Of these, about a dozen were owned by state ministers (one of them even had a college named after him), three by ruling party MPs, and two by opposition leaders. In a sense, it was an extremely productive nexus: the number of private-unaided medical and engineering colleges went up from 7 and 25 respectively in 1984 and to 28 and 120 in ’05! Complaints about quality, capitation fees, excessive admissions (over and above the specific limits) were routine—but no deterrent.

But the situation changed when the Supreme Court intervened and forced Karnataka to revamp its higher education. A state-controlled, centralised system was born, with a regulated admission procedure, fee structure, and sharing of seats in all professional colleges, including private ones. It had a centralised common entrance test (CET) and admission process, conducted by the state. The fee structure and allocation of seats—either by the CET marks, caste-based, or via private management quotas—were to be decided by the state.

BITS Ranchi

Under the 1993 CET system, the seat-sharing ratio between the state and private managements was fixed at 85:15, or 85 per cent to be allocated by the state on the basis of CET marks. Of the 85 per cent, half were allocated to students based on merit rankings, and the rest were reserved for Dalits (23 per cent) and backward classes (27 per cent). Within the merit and backward classes quotas, there was a further 10 per cent reservation for students with a rural background. The annual fees were fixed by the state for its 85 per cent seats, and the managements could charge whatever they wished to in the case of their 15 per cent entitlements.

For nearly a decade, until the system got rusted, it enabled backward class and Dalit students to secure professional degrees. Thus armed for the new economy, many of them joined public and private sector firms. Their earnings rose and, soon, they became a part of the growing middle class. The process started decades ago with reservations; the CET only hastened the growth of this middle-class subset.

In the 1960s and 1970s, students from IITs and other engineering colleges joined the public sector in a big way. Nehru had adopted a socialist model and economic planning as the foundations for India’s growth, opening up a huge swathe of opportunities for the educated middle class. This was more evident during the Second Five-year Plan, when Nehru had come into his own after the death of two of his worst 'critics', Gandhi and Patel, and felt freer to pursue his vision.

The private sector became the most preferred destination for professionals once Rajiv Gandhi allowed the entry of mncs in several sectors. During the 1980s, hundreds of joint ventures were inked between Indian and foreign companies. After being kicked out the country in 1977 by the Janata regime,IBM came back. And Rajiv Gandhi allowed Pepsi to enter the lucrative soft drinks market. The engineers continued to be in business due to the growing demand from the private sector.

Post-reforms, the dynamics changed in favour of foreign firms which had started setting up fully-owned Indian subsidiaries. Y2K was quite the defining moment for software—literally and metaphorically—as the world recruited Indian engineers to get rid of that virtual, inexplicable—and harmless in retrospect—bug. By the beginning of this century, offshoring and outsourcing became the new global mantra, establishing India firmly on the global map. In due course, Indian professionals became one of the most-sought-after ones.

Meanwhile, with reforms, the buzz in technology was spilling over into the larger social domain—showing in an outward boom in sectors ranging from more core ones like telecom and healthcare to ‘softer’ professions like fashion and hospitality. Students flocked to join institutes offering courses in these ‘other’ sunrise sectors. Although an engineering, medical or MBA degree was still the priority, many students decided to enter the new areas, where personal and sectoral growth was likely to be much faster. It also gave birth to risk-takers who were even willing to go on their own.

50 years of IIT—its alumni with Bill Gates, San Jose

Sadly, question marks have cropped up over the role of private professional colleges in the 21st century. A few experts think the professional education system is creating a new set of educated elite, as happened in the 1950s and 1960s. One, it’s only the segment with a certain socio-economic profile that gets admission to these colleges. "Success in higher education is predicated on financial resources, knowledge of English, and the ability to invest in coaching. Without these, higher education is hugely skewed in favour of the privileged," says Amita Baviskar, associate professor, Institute of Economic Growth.

One of the main factors is the expense involved. Explains Kranti Kumar, principal, Thadomal Shahani Engineering College, "When I did my engineering in 1968-74, I paid an annual fee of Rs 120. Now, it is Rs 55,000 per year in my college. In the IIMs, the fees are as high as Rs 1.75-2 lakh a year. I don’t know who these institutions are meant for. Any parent with an annual salary of Rs 5 lakh, or less, cannot afford to pay such fees."

But the votaries of privatisation contend that the issue of high fees is irrelevant in an era where cheap financing options are easily available. Moreover, the banks ask students to repay the loans only after they graduate and start earning. And since the starting salaries in the case of good colleges is quite attractive—some engineers earn up to Rs 24 lakh per annum in their first jobs—the loans don’t pinch either the students or the parents. V.V Dewoolkar, dean, K.J. Somaiya Medical College, a Mumbai-based private college, adds that the "earnings of the middle class have increased and, hence, they are able to afford professional education. Most times both the husband and wife are working and they have surplus disposable incomes". Counters Kumar: "But many people can’t even think of taking loans. There are several brilliant students who don’t even think of filling up an IIT or IIM entrance form due to the high fees."

It’s a conflict-ridden domain, and has always been so—perhaps rightly. That is the fuel on which it moves, and thrives. For, when we talk higher education, in a sense, we are talking about the very creation and growth of a modern middle class in post-Independent India. In the past two or three decades, the neo-middle class, with its higher earnings, zooming aspirations and growing confidence helped elevate the socio-economic status of entire segments of our population. Consumerism, the alluring play of brands, the changing patterns of spending—the genesis of this whole new way of being can all be traced to this mass upward movement of millions of Indians.

But now, there is in some form a rethinking among education experts. One section believes in further specialisation—or creating specific skill sets—through higher education. The other believes this is a short-term strategy that can have terrible long-term fallouts. As long as opportunities exist across sectors, and the growth momentum is sustained, professionals can shift across sectors even with specific skills. But if there is a slowdown, they will find themselves unemployable. That is something India, with millions already unemployed, can’t afford.