First-time MP Anupam Hazra’s stint in electoral politics started sometime last year when he had his resume—a PhD-in-progress from Viswa Bharati University—sent over to Mamata Banerjee, the All India Trinamool Congress chief. This is as sure a sign as any of the changes trickling through Indian politics, for rare is the party leader who identifies candidates for tickets on the basis of educational qualifications. That’s exactly what happened in his case, says Hazra. “She (Mamata) wanted someone with an academic background in the party. Besides, I studied in Tagore’s university, which has a historical importance in Bengal; so I sent my CV,” says the 32-year-old, who represents Bolpur, a predominantly rural constituency.

Hazra believes it’s his focus on rural sanitation—he has done some work among Bolpur residents—that swung things in his favour. “You can argue in favour of change at the level of an individual or activist, but to say the same thing as an elected leader, I’m sure, carries much more weight,” he says.

After a high-tech election campaign run by ‘young professionals’—who lobbed an aggressive online and offline high-tech pitch at voters—it’s just as well that the young guard has a toehold in Parliament. But India’s parliamentary democracy is known to serve up a different reality. In fact, despite India’s youthful population, the oldest Lok Sabha members ever have taken charge of the nation. Ironically, this may not be an entirely bad thing, if you go only by the record of the most dedicated parliamentarians in the 15th Lok Sabha. The most active participants in debates between 2009-14 were all in their fifties or sixties; significantly, the top ten possessed a post-graduate degree.

In the previous Lok Sabha, the BJP’s Arjun Meghwal (60), introduced 20 private members’ bills—including one against homosexuality and another to set up a ‘Price Commission’. He raised 749 questions. Samajwadi Party’s Shailendra Kumar Jha (53), a BCom graduate, attended 97 per cent of the previous Lok Sabha’s days in session and participated in 353 debates. P.L. Punia (69), a doctorate holder from the Congress, had an attendance of 99 per cent, where he raised a storm of 656 questions. The fourth, BJD’s Bhartruhari Mahtab (51), a post-graduate in English, asked 395 questions. Finally, Virendra Kumar of the BJP had 96 per cent attendance and raised 280 questions.

The first 30 luminaries on this list, compiled by PRS Legislative Research for the 15th Lok Sabha does not include a single MP in his 30s and only two in their 40s—J.B. Lakshmi (49) of the Congress and M.B. Rajesh (42) of the CPI(M).

However, the fact that the oldest-ever lawmakers have been elected to the 16th Lok Sabha give as many reasons to rejoice as despair. As PRS’s research has shown, there is also no apparent connection between MPs’ youthfulness and their interest in upholding Parliament’s oldest traditions—raising questions or participating in debates. Indeed, PRS, which has analysed the performance of MPs over nearly a decade, has established that there is no connection between their performance and education either.

Ortho MP Shiv Sena MP Shrikant Shinde attending a patient in New Mumbai. (Photograph by Amit Haralkar)

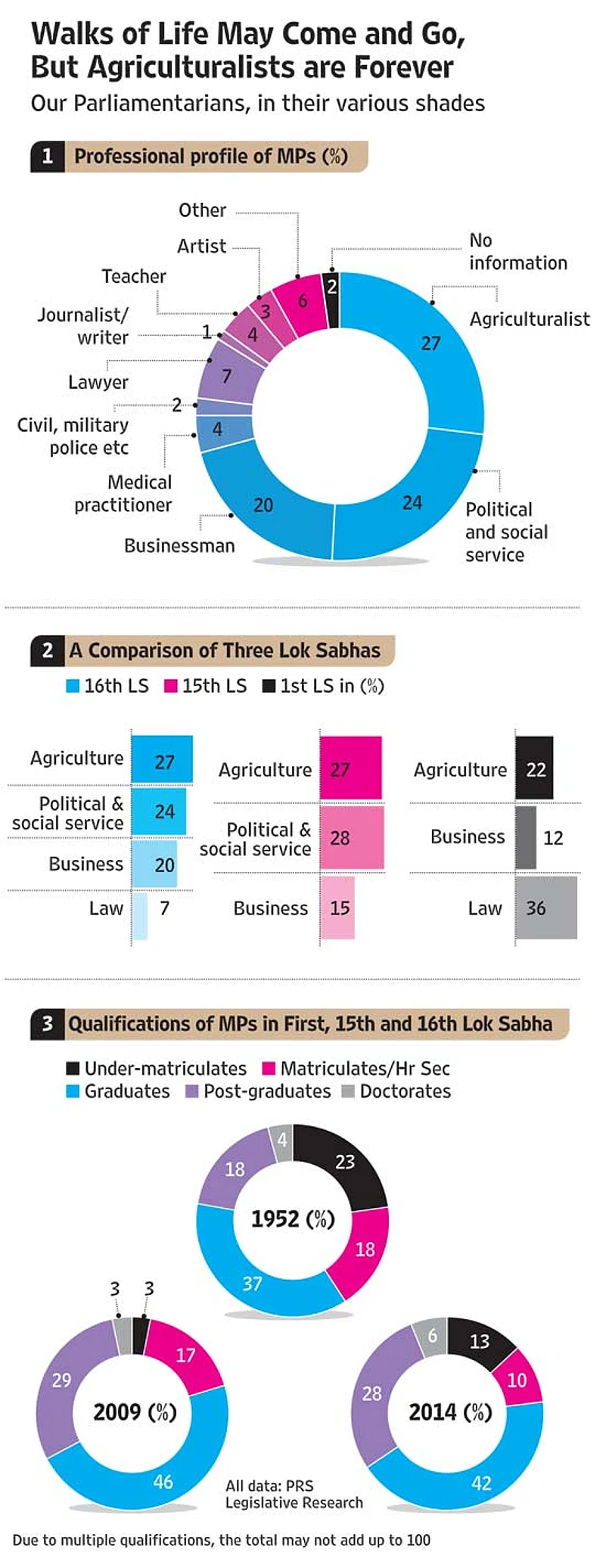

The 16th Lok Sabha has a smaller share of graduates, post-graduates, as well as matriculates compared with the 15th. Conversely, the number of under-matriculates has crossed 1977 levels, beating the last few Lok Sabhas hands down in a race to the bottom of the education bar. At the same time, there are more doctorate-holders this time, perhaps the highest since 1996.

“MPs with professional qualifications display a slowly changing trend. What stands out in the 16th Lok Sabha is the number of MPs who have described themselves as employed in political and social service,” says M. Madhavan of PRS. In the very first Lok Sabha, 22.5 per cent members said they are ‘agriculturists’, which climbed to over 49 per cent in the 12th, and has declined now to 27 per cent. Data for the intervening Lok Sabhas is unavailable.

That said, the 16th Lok Sabha has its own generous sprinkling of doctors (19), lawyers (38) and artists (18), in addition to a handful of doctorates and a few with professional degrees, such as in social work and education. Many of them are first-time MPs with advanced degrees or people who held positions in government organisations.

Dr Dharam Vira Gandhi, the Aam Admi Party’s Patiala candidate, contested and won his first elections to become one of four AAP MPs in Parliament. His entry into politics, he says, was more of an attempt to reclaim the political space on behalf of educated, middle-class elites. “I felt that if we don’t get into politics we leave this space to corrupt elements...it isn’t enough to just stand by and complain against the system,” says Gandhi, who describes himself as the product of a post-independence idealism. A medical doctor by training and a teacher by profession, he was pulled out of his post-retirement life by AAP’s rise. He plans to raise issues related to price rise and Punjab’s drug menace in Parliament.

Each of the new entrants hopes to make a difference to politics where it matters most—in conducting criminalisation-free politics. As a recent report released by the Association for Democratic Reform (ADR) points out, criminal charges have been framed against 53 MPs, all of whom stand in violation of the Representation of People Act. “We expect the government, which has come to power with a full majority, to take the correct steps against criminals in politics,” says Prof Jagdeep S. Chhokar, founder and trustee, ADR. This means these cases would need to be ruled upon by the courts within a year, as per a Supreme Court ruling earlier this year.

Successive research has shown that there is no connection between the educational qualifications of MPs and their criminal records. “They are both separate and distinct categories,” as PRS’s Madhavan points out. The importance of education arises only in terms of the expertise that an MP will bring to his area of specialisation. Professionals entering politics also opens doors for new entrants, like people without political backing, to join the electoral fray.

Both Gandhi and Hazra, for instance, come from non-political families. Shrikant Shinde, another young doctor and winning candidate from the Shiv Sena in Maharashtra, does come from a political family, which meant the option was always open for him. The 32-year-old orthopaedic surgeon decided to take the plunge only when he determined to continue his work as a doctor while looking after his constituency (Kalyan, Maharashtra) as well.

Days before the polls, he sat for his MS exams, says Shinde. “I plan to join the 18 other doctors in Parliament in a group that will focus on improving hospitals and healthcare in rural areas,” he says. The Kalyan constituency is also 50 per cent rural and the doctors in the Lok Sabha have already discussed the changes they can make in rural healthcare. “The idea of being in politics did come from my father (Eknath Shinde, SHS legislator from Thane), but the final decision was taken only when I realised that the country is changing rapidly—there is much more acceptance of qualified professionals in public life,” he says. That can only augur well for Parliament.