Rich and industrialised nations may have decided to gloss over Narendra Modi’s past, especially his alleged role in the 2002 Gujarat riots, in their desire to participate in and reap the benefits of India’s economic growth. But sections in these countries remain active in their opposition to Modi, some even going to the extent of seeking prosecution of the prime minister when he sets foot on their soil.

Significantly, the Gujarat issue has again reared its head, and at a time when a series of attacks on churches and Christians in India has led western commentators to raise questions about religious freedom in India after May 2014, when the BJP came to power. The demand for Modi’s arrest has now come from an expatriate group of Sikhs, a community the PM has been trying to woo by offering financial, judicial and political assistance to victims of the 1984 anti-Sikh riots in Delhi that took place under a Congress regime. But this definitely has not worked to dilute the Canadian group’s stand against Modi for his role as the chief minister of Gujarat in 2002 during the anti-Muslim pogrom when thousands were killed and injured.

On Thursday, Modi left on a 10-day three-nation tour that will take him to France, Germany and Canada. There is now a demand that criminal proceedings should start against him when he arrives in Canada’s capital Ottawa on April 14.

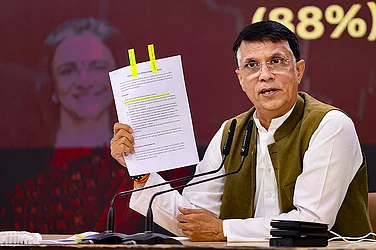

The Sikhs For Justice (SFJ), an advocacy and human rights group based in North America, has filed a complaint with the attorney-general of Canada requesting that criminal proceedings be initiated against the Indian PM for “torture and genocide” under Canadian law.

“Prime Minister Modi will be travelling to France, Germany and Canada,” foreign secretary S. Jaishankar told the Indian media on the eve of his departure. “A common theme of these destinations is that all of them are industrialised democracies. We have considerable economic interest in partnering with these countries which is very relevant to our industrial programmes,” he added.

In all three countries, Modi will engage with the political leadership, industrialists and members of the Indian community. In Canada, where he will visit three cities—Ottawa, Toronto and Vancouver—he is scheduled to interact with representatives of the 1.5 million-strong Indian community, a majority of whom are Sikhs. But in between the niceties, the PM may have to deal with an awkward situation involving banners and slogans, with some seeking his arrest.

Says Gurpatwant Singh Pannun, legal advisor of SFJ: “Canadian law provides for the prosecution of individuals who commit acts of official torture outside of Canada where, after the commission thereof, they are present in Canada.” The complaint, filed with Attorney-General Peter Mackay, alleges that in February-March 2002, Modi “aided, abetted and counselled in relation to the massacre of thousands of Muslims in...Gujarat, while he was the chief minister”.

In the past, SFJ had also sought similar criminal proceedings against Congress president Sonia Gandhi and other senior members of the party. But none of their efforts have been successful. Most possibly, their pleas to bring Modi to justice would meet a similar fate. However, there are indications from western diplomats that in between discussions centering on India’s attractiveness as an investment destination, there could also be opportunities to slip in concerns regarding the status of religious minorities.

Indian diplomats might well ensure that if such concerns are raised by Modi’s hosts, they remain within the confines of closed-door meetings. But ignoring them completely could cost India dearly in the days to come, both in attracting advanced technology and investment from the West and in maintaining social harmony within the country.