ELECTION sloganeering this year will echo the shots in Kargil, not India's population explosion. Shrill propaganda reverberating with misplaced priorities will ignore, yet again, the mother of all problems in our jampacked nation. A problem that's given birth to our billionth citizen this week.

So say the United Nations' demographers who have declared that India, which adds more people to the world than any other nation each year, will officially cross the billion mark just in time for her 52nd Independence Day. By 2016, the country will have more people than all of Europe and the rest of the industrial world, excluding Russia. The UN has also predicted India's overtaking China as the most populous nation in the world in the next four decades. Reasons which move World Watch, the Washington-based environmental research agency, to comment: Reaching a billion mark is not cause for celebration in a country where almost half the adults are illiterate, more than half the children undernourished and one-third the people below the poverty line.

Predictably, our government's response has been to deny the UN calculations and say that the billion mark will be crossed not this week but sometime in May 2000; that there are still nine months and 12 million babies to make that mark. It has its indigenous Technical Committee on Population Projection to support that claim.

Of course, one could investigate which set of statistics is false. But why bother? Numbers anyway don't shock a people like us already suffering from severe demographic fatigue. Moreover, it's ridiculous trying to pin a date to the 'billionth' birth as if it were Diwali. Such fine-tuning is impossible when such large numbers are involved, says demographer Ashish Bose.

Numbers so huge, and cited so often, that we've been as desensitised to them as our politicians. What does a few thousands more or less than a billion matter to anyone? Little, really, if the opinion poll conducted by a national daily earlier this month is any indicator. The survey had 48 per cent respondents voting Kargil as the most important poll issue. Other areas of worry included the stability of the government, price rise and able leadership among nine topmost concerns; population didn't even make it to the list.

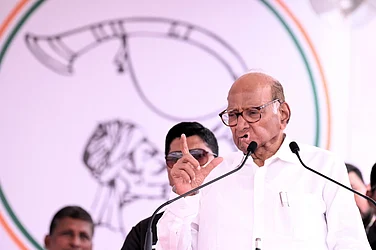

Yet, our humongous population count affects us as much, and maybe even more, than the coalition arithmetic that hogs our headlines and attention. We feel its burden as we jostle for opportunities in education, jobs, housing and congested roads. Occasionally, politicians do pay lip service. We've always given top priority to population control, but we didn't have time to do much about it, reasons the bjp's Sushma Swaraj. Accuses the cpi's A.B. Bardhan: Except using coercive methods during Emergency, the government hasn't dealt with the problem. Jairam Ramesh of the Congress confesses to his party's past 'squeamishness' on the issue (after Sanjay Gandhi's body-snatching sterilisation drives), but reveals its new intent to introduce socio-economic and cultural programmes in the backward areas to tackle the problem.

Clearly then, little meaningful has been said about population control. Probably even lesser done. Consider the latest government statistics which reveal that a mere 44 per cent Indian couples use any contraception at all. And other statistics which show that about half (49 per cent) of couples 'never discuss family planning among themselves'.

'Discussion', it seems, has been a casualty to a slew of past policies which,despite expressing concern to link family planing to gender sensitive development processes,continued to place responsibility on women to monitor population growth. Plans and proposals, seemingly drafted for women's well-being, often turned out to be mere means to achieve demographic targets. Coupled with the fact that negotiating positions between the genders is unequal, reproductive behaviour has progressively seen women being assigned disproportionate responsibilities without having any decisive powers.

Any which way one looks at the statistics, family planning isn't a shared responsibility. Sterilisations being the most popular means of contraception in the country, 98 per cent of them are tubectomies. Much less complicated to perform, vasectomies are perceived as tampering with manhood and rare. Even condom usage is a meagre 2 per cent, and could dip even lower with it being advertised less and being pushed mostly as a protection against hiv-aids. With the government's latest interest in introducing injectible contraceptives for women,opposed by feminist groups for their side effects (see A Misplaced Conception),as a part of its birth control programme, it seems that women will continue to bear the burden of birth control.

A fact endorsed yet again in the current lively campaign dubbed Goli ke Humjoli (Friends of the Pill),a major private sector initiative to popularise the Oral Contraceptive Pill. Aimed at the urban, middle-income segment, the campaign tries to dispel myths about the pill's side effects. Says Sashwati Banerjee of Commercial Market Strategies, technical advisors to the project: After all, it's a social reality that women, not men, are the main users of contraception in our country. At least let us give the women their right to an informed choice. Let's tell them about how safe and reversible each method of contraception is.

But why have men not been part of what was to be a shared responsibility? Mainly because we always took a target approach to the issue, says Dr Saroj Pachauri, regional director for South and East Asia at the Population Council. Population control became about family planning and the latter in turn became synonymous with contraception; since most contraceptive technologies are designed for women, only they were targeted. Also, the primacy of the medical profession made drugs, technologies and surgical interventions 'solutions' to complex reproductive health issues. So social, cultural and gender dimensions were ignored. Add to that discussions on sexuality being taboo, and it's easier damaging the concept of shared responsibility.

Yet all's not lost. At least on the level of internationally-endorsed intent and government paperwork, if not in terms of ground-level reality, there has been a paradigm shift in our population policy with the introduction of the Reproductive Child Health programme since October '97. The earlier 'number-driven controlling of population growth' approach has given way to providing healthcare and other developmental inputs to people. Also, now population programmes are to be rooted in respect for women's reproductive rights and choice and a concern for women and child health.

We've placed the population programme squarely in the development context, and decided to move away from demographic goals to individual and community needs, says Meenakshi Dutta Ghosh, joint secretary (policy) in the family welfare ministry. District level monitoring, health facility surveys, revamping mindsets of the health workers used to functioning in a totally different framework,all this is being done.

Most significantly, says the bureaucrat, Andhra Pradesh's success in non-scalpel vasectomies has encouraged the ministry into believing that efficient health delivery systems make men supportive participants in reproductive health programmes. It's telling that the largest team of non-scalpel-vasectomy-trained doctors (69) have managed 21,758 operations in just a year. We must talk about this success. If only to convince other men that it's alright to undergo this minor operation. We've already decided to enhance our information budget on vasectomies from Rs 4 crore to Rs 9 crore.

But it's this big money that is part of politics of contraceptives, says Laxmi Murthy of Saheli, a feminist activist group. The onus is on women not because it's some villainous conspiracy against their health but because of business interests in a country that is the world's largest buyer of contraception. Hormonal preparations and tubectomies are big money: much more than the basic condom. Somebody earns money even if the government subsidises it for the end user. Why doesn't the government push diaphragms and cervical caps? Perhaps because they are reusable and not as profitable, she points out. Add to that the fact that women are the 'better users' of contraceptives, the 'softer targets', and you realise why nobody's bothered with involving men.

The fear, however, is that involving men in reproductive health through sustained interventions might rob women of their limited rights to privacy and control over their bodies. Perhaps, then, these rights will have to be redefined. Also, maybe the demand for men's participation and support will have to come from women. That will mean changing society. And that could be a long haul.