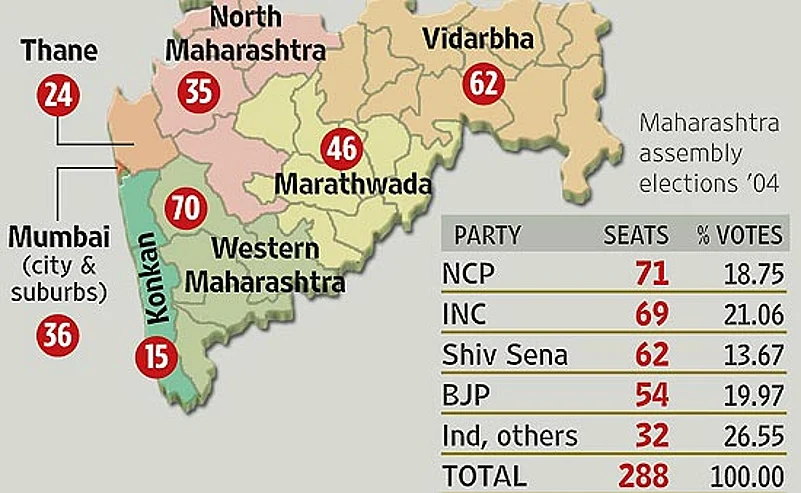

Matchpoint Maharashtra

Region-wise seats break-up

Rural Issues

- Agrarian crisis, lack of roads, irrigation, load-shedding and some key rural issues.

- Farmers’ suicides from increasing debts.

- The fall in foodgrains production. Oilseeds and other commercial crop output has also dipped sharply.

Urban Issues

- Clear division of issues in urban, rural Maharashtra. Urban areas now comprise about 40 per cent of population.

- The state has the highest number of urban poor in the country, at 1.46 crore.

- Security, employment, housing, transport are some key urban issues. Frequent violent clashes on political and communal lines is a major urban issue.

***

“Satte chi killi dhya, chamatkar ghadvun dakhven (Give me the keys to power, I will create miracles).” That’s 41-year-old Raj Thackeray’s challenge to a rapt audience on the opening night of his most important election campaign ever. There is a loud roar of approval, much clapping and cheering. Raj, the rebel dichotomous—he revolted in the Shiv Sena but remains steadfast to its ideology—senses that rare moment when orator connects with audience and draws sustenance from them. The man, as everyone around says, is on a roll. It may not catapult him yet to a position from where he can “create miracles”, but there is no denying that he is more than a flash-in-the-political-pan of Maharashtra.

If Raj has his way, if events unfold in rhythm with the lines on his drawing board, if his three-year-old Maharashtra Navnirman Sena (MNS) can open its account in the state legislature on October 22 when votes will be counted, he will have come much farther than what he had imagined for himself five years ago. Then, he was campaign in-charge of the Shiv Sena, toeing cousin and party working president Uddhav’s mantra on all things that mattered, grudgingly travelling across rural Maharashtra (Raj is undoubtedly more urban-oriented and urban-centric) and sharing with a few close friends his ideas for doing things differently. Even then, he believed he suited the top slot better. Now, five years later, he is in the top slot, though not of the party he coveted.

Buoyed beyond expectation by his MNS’s vote-garnering abilities in the Lok Sabha elections, Raj has embarked on a grand plan to do an encore in the assembly polls. He has over a 100 candidates in the fray, many of whom will undoubtedly split the Sena’s traditional vote, and allow the Congress or NCP contestant to steam ahead there. But with only so many candidates even contesting (it’s a 288-member assembly), Raj cannot even imagine himself to be holding “the key to power”. But he is a caricaturist, cartoonist, given to figurative expressions. And, figuratively speaking, his motley group of MLAs—most analysts concur the party could win about 10-12 seats—may be the key to supporting the next government of Maharashtra.

The MNS has the usual stuff on offer: houses and jobs for locals, work permits for outsiders, Marathi as lingua prima and so on. The manifesto doesn’t really matter. The violence and limitedness inherent in the ideology doesn’t either. What matters is Raj’s connect with an electorate that is increasingly tired of Uddhav’s style of functioning, his relatively inclusive agenda, his inability to put a non-performing government on the mat. Raj reminds them of the old Bal Thackeray, a promise of aggressive opposition that Sena ideologues and cadres so love. “It is as seductive in 2009 as it was in the 1960s and 70s,” points out Suhas Palshikar, political science professor and researcher at University of Pune, “but it does not address the issues of urbanisation”. For the MNS now, Raj is himself the ideology, the mascot, the star campaigner, the decision-maker, the first and last word on everything.

Raj’s rise, so to speak, coincides with the fading control of political patriarchs over their party structures, workers and the electorate. This assembly election, therefore, has an unerring undercurrent of rebellion spread across parties. Leader against leader, worker against worker, aspirant against aspirant—the disease, as NCP leader and deputy CM Chhagan Bhujbal remarked, is spreading like swine flu in all parties.

NCP boss Sharad Pawar camped in his Baramati home for two days, attempting to quell the rebellion skewing up their poll scenario. What could be more telling than the fact that NCP state president R.R. Patil himself faced a rebel (pacified at the last minute with the promise of “being accommodated later”). Party leader in Kolhapur and former cabinet minister Digvijay Khanvilkar, who is contesting as an independent, remarked that “there are too many interests now guiding the distribution of tickets”. He might just spring a surprise on Pawar. So could Dilip Sopal in Barshi, near Pawar’s hometown.

The Congress has its share of rebellion too, led by Sunil Deshmukh in Amravati. “It is now ghar ghar ki kahani,” says Union minister and former chief minister Vilasrao Deshmukh. The popular term could well be taken to mean the plethora of tickets that have gone to sons and daughters, nephews and nieces, in both the Congress and the NCP. Such large-scale rebellion has not been witnessed in the last three assembly elections, analysts say. In the sugar belt of Satara district, there are five locally prominent leaders standing as rebels in the eight seats (including Shalinitai Patil, widow of late chief minister Vasantdada Patil). One incident best typifies the internal dissent in the Congress—as chief minister Ashok Chavan drove in to support his colleague who was filing his nomination papers in Loha, his car was greeted with chappals and stones.

Sonia Gandhi, Ashok Chavan, Rane and other Congress leaders in Mumbai

Almost half of the 288 constituencies have rebels in the fray. Sada Sarvankar, committed Shiv Sena leader who railed against the Muslims and the Congress to form his political base in Mumbai’s Dadar area, was denied a ticket. That evening, he was persuaded by Narayan Rane (an ex-Sainik himself) to hop over to the Congress. The amazing thing was Sarvankar’s candidature was okayed in Delhi. “He was spewing venom against the Muslims in the morning and was wearing a skull cap and going to a dargah in the evening,” says a bitter Ajit Sawant, who instantly formed a “Congress Bachao Andolan to save the party from such elements”. Sawant was a contender in Dadar.

Meanwhile, the most violent act so far has been the firing on BJP candidate Siddharamappa Patil in Akkalkot, allegedly by supporters of the Congress’s Siddhram Mhetre, minister for state for home. Patil’s colleague died on the dais, three others were injured. Analysts reckon that rebels could impact the results in as many as 50 seats, leaving all four major political parties short of their projected wins. “The independents, or rebels, are positioned to get about 22 seats. Add to this, the few seats that smaller and local parties could win. This is the tally that the majority party, or alliance, will have to work its way around if it has to form government,” says B. Venkatesh Kumar, political scientist at University of Mumbai and director, Rajiv Gandhi Institute of Contemporary Studies.

Vinod Kambli, CPI(M)’s Sitaram Yechury, Sanjay Dutt, RPI’s Ramdas Athavale et al at a Third Front rally

So where do issues figure in this election, dominated as it is by personalities, egos and rebellion? Anti-incumbency, all the Opposition parties say, is the most significant factor, given that the state has slid down on most development parameters in the decade the Congress-NCP alliance has been in power. Yet, anti-incumbency does not figure in campaigns except as mandatory lip service. This, says Palshikar, is partly because anti-incumbency has ceased to matter as much as it did in the last decade. Elections are now about managing the numbers game, not addressing issues.

Sena Rajya Sabha MP Bharat Raut explains that it’s not that they are not raising issues, it’s more that there are two distinct campaign strategies in place; the urban one focused more on identity and security issues while the rural one is centred on lack of development. In all the cacophony, no one is reading manifestos. The Sena-BJP one reads like a veritable wish-list for both urban and rural voters—no hike in power tariff, no acquisition of farmland for SEZs, sops for debt-ridden farmers, cheap loans, raising a “Tiger Force” of jawans to defend Mumbai-Pune-Nashik. The Congress-NCP is asking for votes to keep “communal forces out of power and take the state forward”. It’s an old and tired campaign pitch; Congressmen hope that Rahul and/or Sonia Gandhi will be able to breathe new life into an old song when they come campaigning. And chief minister Chavan is looking to keep his job. “In the nine months since I took over, there have been two elections,” he told Outlook, “I won the 20-20 (Lok Sabha) for the party, this is my Test innings and I want to win again.”

There are others talking of a Congress win too, but that’s segued with talk about a covert deal with the MNS boss. No wonder then that allegations of Congress backing Raj Thackeray simply do not subside. Raj has challenged his detractors to prove it. The Congress and Raj could do with each other’s benign assistance, but in a scenario where a Sena-BJP alliance scores over the Congress-NCP, Raj will have to take his toughest judgement call yet—does he assist in bringing the Sena-BJP to power, and perhaps bargain that Uddhav stays away from the chief minister’s chair?