Chennai, the city that sleeps at eight, twinkles at night to the taalams of south Indian classical music and dance in the month of Margazhi. The season brings together some 60 sabhas or concert halls hosting over 1,000 Carnatic music and Bharatanatyam performances, folk festivals and literary and poetry readings across different venues in Chennai.

Now if there’s one art form that has lent itself to much debate across centuries over content, form, gender, class and community, it has been Bharatanatyam, performed as it is by old and young, in forms that are traditional, modern and contemporary today.

Bharatanatyam traces its roots back to ancient temple art forms. It’s easy to call it centuries old, stuck in tradition, dealing with myths, bhakti and tales, but it’s ever modern. Unlike Kathak or Odissi, Bharatanatyam is held up more as an example of an Indian dance form that has undergone several transformations. Yet, in contemporary times, it has also been held up as a cultural emblem of rigid traditional art, which its performers contest.

It is called classical and traditional but over the years this aspect of south Indian dance has been questioned. And in the last couple of decades, even more so. Ask Anita Ratnam, who learnt Bharatanatyam the way it was taught by Rukmini Devi Arundale and others from the Thanjavur belt in the turn of the 20th century. “Bharatanatyam is a natural way of moving for me, but the style I learned from my gurus is a far cry from what I do now,” she says.

Today, she may be one of Chennai’s prominent performance artists, but her dance is contemporary, bringing a new vocabulary to old tales of myths and movements that is free to adapt and adopt movements from Bharatanatyam, Mohiniattam, Chhau, yoga, Tai Chi and even the temple sculptures of yore. Gender, mythology, ancient tales from Greece and India, Shakespeare, even multimedia presentations are the inspirations for her these days.

“Bharatanatyam, as we know it, is not an ancient art but a modern one,” says Ratnam. It was reconstituted in the mid-20th century from the old forms of Saadir and Dasiattam as ‘Bharatanatyam’—named in the new nationalist spirit. From an art form it transformed into a cultural artefact, she says.

This season will see many such instances where unlike Carnatic music, Bharatanatyam will be presented in different forms besides the known one. ‘Fire and Ash’, a production, brings Bharatanatyam, music and theatre together to present the ancient concept of Shiva in contemporary metaphors, set to Bengali, Telugu and Kannada poetry. Ratnam presents ‘Padme’, a group choreography that will present six young dancers combining Odissi and Bharatanatyam.

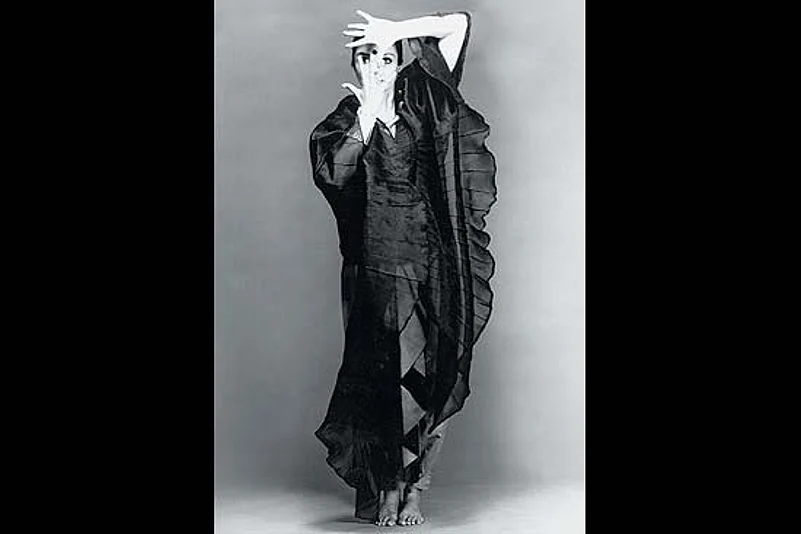

A few more mudras Anita Ratnam. (Photograph by Sanjeev Nair)

Ratnam is not the only one charting new roads today in south Indian classical dance. Indeed, there is no better proof than the coexistence of two forms of the dance that emerged from the temples of Tamil Nadu centuries ago.

Bharatanatyam was founded by Rukmini Devi Arundale in Kalakshetra in the 1930s and soon thereafter, within “cycling distance” by the Bay of Bengal in Chennai, emerged Chandralekha who is called the founder of modern dance in India. Both learnt their Dasiattam from gurus and temple dancers. But they interpreted it in two strikingly different ways. Rukmini Devi interpreted the Hindu mythologicals and classics and composed dance dramas and performances with a rigorous grammar and tone of piety, which are considered the hallmark of what is popularly recognised as Bharatanatyam today. Chandralekha invoked the secular, the body and the sensual to make her own dance vocabulary. If Rukmini Devi designed costumes and jewellery for dance, Chandralekha chose to dance in dark cottons without the embellishment of trinkets.

The emergence of a unifying south Indian classical dance tradition called Bharatanatyam itself was a modern post-Independence thing. It meant that dance left the temple prosceniums, its confines of one community as Bharatanatyam found a huge following among educated middle class women in Madras.

The domestication of dance made it available to all, it moved from a “paradoxical subculture, that of the sacred and profane devadasis. We need to realise this form we are studying and performing was couched and nurtured in a paradox”, says Navtej Johar.

Johar would know better. His training was in Kalakshetra, almost planets away from his home, Delhi. “I took to it like a fish to water. I really made it my own when I started to experiment with it and open it to interpretations that were directly influenced by my being not only a Punjabi but also a Sikh,” he says.

Even the dancers who have earned the critics’ nod for their “pure nritya”, implying tradition and classicism, say that Bharatanatyam allows a greater freedom to bend conventions. “Tradition has always been tweaked in Bharatanatyam,” says Alarmel Valli, India’s prominent performer in the classical Thanjavur style. Valli may choose to dance to compositions set to song many centuries ago, “but my interpretations are based on how I feel and think as a modern independent woman,” she points out.

Ten years ago, during the season, the Chennai Museum Theatre came to the hub as an alternate space for traditional dance performances. The Other Festival brought theatre, dance from all over the country, other performance artistes. The current change in steps in Bharatanatyam has more to it, point out the dancers. Today’s performances have to factor in many things, like younger audiences who find it difficult to understand ancient poetry and music. And young dancers who often do not speak Tamil or Telugu, or can’t even sing the songs set to dance like an earlier generation. Today’s young dancer concentrates on “his/her body and athleticism”, is interested in experimenting, toying with the modern or new.

“Frankly, Chennai’s changed so much today, as much as its dance. The smug sabha mama has a huge change facing him,” says Ratnam. Meanwhile, Bharatanatyam continues dancing to traditional steps with a contemporary twist.

By Sudha G. Tilak in Chennai