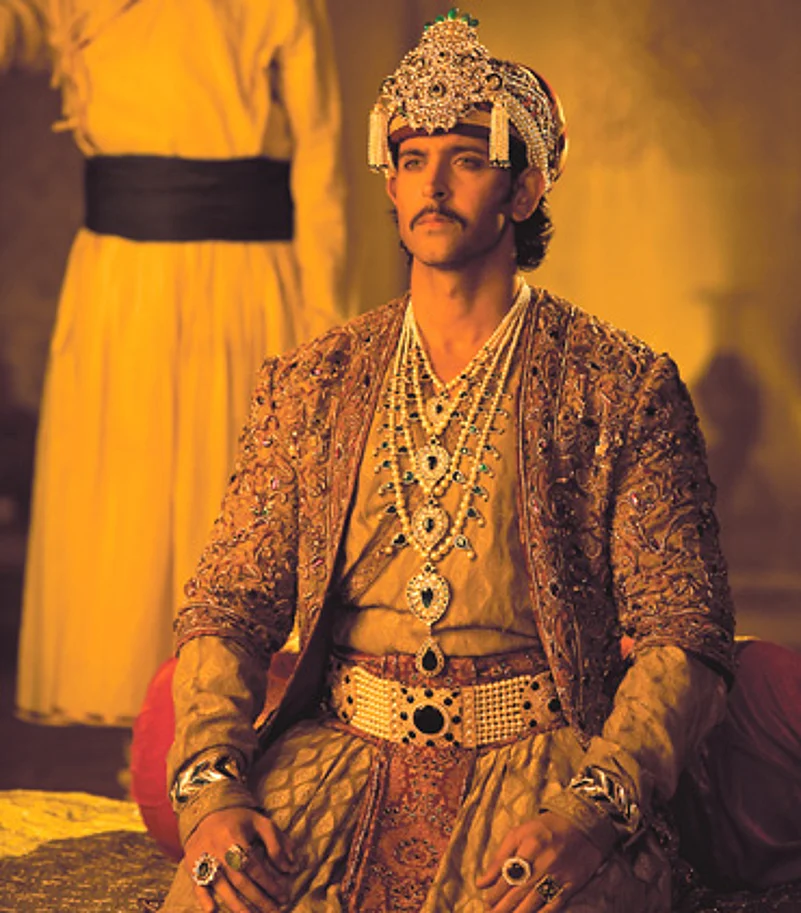

Hrithik portrays the benevolent Akbar

In modern times, when Islam has been a religion under siege, Akbar is made the torch-bearer of the liberal, progressive and tolerant face of Islam. "He was a true Indian ruler, he appointed Salim, his son from his Rajput wife, as his successor. He had members from native Indian communities as part of his nobility and five of his provinces were led by the Rajputs. He called for radical reforms like banning sati and forced circumcision, he laid down a progressive education system and abolished the pilgrimage tax and jaziya, brought in land and tax reforms; he was far ahead of his times," says Shah Nadeem, a history lecturer at Delhi's Zakir Hussain College. The modern outlook is evident even in minor scenes like when he talks of treating prisoners of war with respect. Or take the scene where he dances in a trance to the beautiful Sufi number, Khwaja mere khwaja. "It is a visual reference to Din-e-Ilahi, his study of religions and his belief in the spiritual than the ritual side of all religions," says Gowariker. "He opened his ibadatkhana for debates and discussions on all religions," says Nadeem.

The contemporary tone goes a step further. Till Akbar came, the Khiljis, Lodis, et al were seen as invaders and marauders who plundered and looted India. He was the one who built and consolidated the empire and decided to belong rather than be perceived as a gair mulki or foreigner—a point that strongly echoes the current debates on Sonia Gandhi's Italian roots. "The Mughals transcended the Muslim and the Rajput to become Hindustani," says Visvanathan. In the film, he talks of building a "muqammal Hindustan" (unified India), of letting go of religious prejudices.

Though Gowariker's intentions in resurrecting Akbar have been noble, the criticism comes for his execution of these ideas. "The film does tackle issues like secularism, Hindu-Muslim unity and national integration head-on, but so head-on that it is hammer-headed in its lack of subtlety. Also because of its bottom-numbing length and langorous pacing these well-meaning messages get buried deep in the film," says film writer Naman Ramachandran. According to him, Mughal-e-Azam was far more remarkable for its matter-of-fact treatment of religion, it noted the examples of tolerance without belabouring the point, was unselfconscious in its display of religious harmony. But times have changed since those more innocent, idealistic days. So have the ways to tell stories from our past.