In Kerala, a majority of writers and intellectuals have historically aligned themselves with the Left.

Sahitya Akademi president K. Satchidanandan has advocated a change of government in the next election.

They fear that a third consecutive victory would jeopardise Left ideology and encourage authoritarian tendencies—an argument that others dismiss as lacking political reasoning.

Speaking Truth To Power? What ‘Intellectual Dissent’ Means For Kerala’s CPM

The recent statements by some writers have become a major political talking point in poll-bound Kerala.

When academic and political theorist Edward Said elaborated on the role of intellectuals in society, he was outlining the ethical qualities an intellectual ought to possess. He was certainly not writing with India—or Kerala—in mind. Yet the role Said ascribed to intellectuals, particularly the duty to “speak truth to power,” continues to resonate strongly in the present-day Kerala.

Edward Said characterised the intellectual as one who resists “easy formulas” and “ready-made cliches,” and who remains sceptical of the reassuring narratives offered by the powerful and the conventional.

Said’s formulation is invoked in Kerala when, on the eve of Assembly elections, a section of intellectuals—some of them long aligned with Left ideology—becomes sceptical of the policies pursued by the Left government and openly endorses a change of government.

The intellectuals and writers who took the stand that the Left should not be voted back to power framed their intervention as an act of ideological preservation rather than political opposition. Their argument was that an uninterrupted continuation in office risked eroding the Left’s ideological coherence, potentially leading to a rupture similar to what unfolded in West Bengal, where prolonged incumbency hollowed out the party’s ideological and organisational base. The consequences of that rupture, they argued, continue to reverberate in Bengal’s political landscape, generating persistent turbulence within the Left camp.

This line of reasoning entered the wider public domain following a statement by poet and Kerala Sahitya Academy president K. Satchidanandan. His intervention triggered a debate that extended beyond the immediate question of the ideology being practised by the Pinarayi Vijayan–led Left Democratic Front (LDF). It reopened a broader inquiry into the role of writers and intellectuals in shaping political judgment in society, whether their interventions merely reflect elite dissent or actively influence electoral choices by reframing political decisions in ethical and ideological terms.

According to K. Satchidanandan, a continued Left rule in Kerala risks not merely electoral fatigue but a deeper erosion of ideological clarity. Prolonged incumbency, he argued, can foster centralisation of authority and blunt the self-corrective mechanisms essential to a movement that historically defined itself through internal debate. Drawing on the experience of West Bengal, he suggested that the Left in Kerala should be prepared, if necessary, to return to the Opposition in order to preserve its ideological integrity.

The significance of Satchidanandan’s intervention lay not only in its content but also in its source. For decades regarded as a fellow traveller of the Left—his public critique disrupted the assumption of a stable cultural-intellectual consensus around the ruling front. His repeated assertion that “for democracy, rotation of power is the best safeguard” reframed the debate from partisan loyalty to democratic principle.

The reaction was telling. Sections of the CPI(M)’s online support base denounced him as a traitor, reflecting an increasingly polarised digital political culture. Yet the party’s senior leadership adopted a more measured tone, refraining from directly disowning him—an indication perhaps of the symbolic capital he commands within Kerala’s literary and progressive circles.

Satchidanandan’s position also emboldened other writers. Sara Joseph publicly endorsed similar concerns, intensifying the debate. Award-winning author P. F. Mathews went further, arguing that the Left in Kerala had “ceased to be Left” in substantive terms. Talking to Outlook, he cited the government’s handling of the ASHA workers’ strike and its stance on the Modi government’s PM-SHRI project as evidence of what he described as a drift away from foundational Left positions.

Notably, Satchidanandan is not a CPI(M) cardholder, but his long-standing opposition to right-wing politics and his involvement in progressive social causes positioned him within the broader Left cultural sphere. His unease with the Pinarayi Vijayan government became explicit during its confrontational approach to the striking ASHA workers.

However, when it comes to assessing the actual electoral impact of this intellectual “revolt,” opinions diverge. Not all writers are convinced that such interventions carry decisive political weight.

Renowned English novelist Anees Salim, who resides in Kochi, argues that the political positioning of intellectuals is unlikely to influence voting behaviour in any substantial way. In his view, electoral outcomes are shaped more by prevailing political currents than by statements from cultural figures. “There is already a perception, especially after the local body elections, that the Congress-led UDF is poised to come to power,” he observes. “The statements that are now emerging may reinforce that perception. Beyond that, they do not carry much relevance.”

Anees Salim also raises a question of credibility. Writers who had previously engaged with or worked alongside the government, but who choose the eve of an election to publicly distance themselves, may face scepticism from sections of the electorate. Such timing, he suggests, can make the dissent appear less like principled critique and more like strategic repositioning.

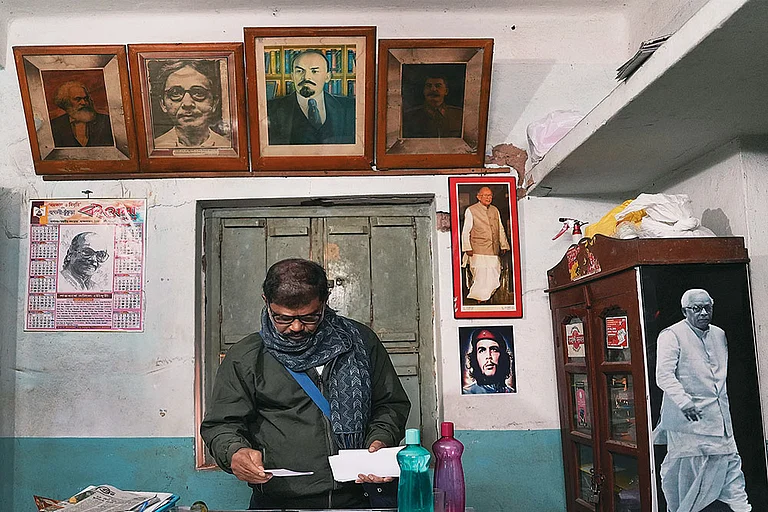

The Left in Kerala has historically cultivated a symbiotic relationship with intellectuals who were not necessarily party members but broadly shared its ideological commitments. From its earliest years in power, the Communist movement in the state drew legitimacy not only from its mass base but also from its engagement with the cultural and literary spheres. The first Communist government led by E.M.S. Namboodiripad in 1957 included figures such as V.R. Krishna Iyer—who would later serve as a judge of the Supreme Court—and the noted literary critic Joseph Mundassery as ministers. Their presence signalled that governance, for the Kerala Left, was not conceived merely as administrative control but as an extension of a larger intellectual and social reform project.

The party’s engagement with writers extended into the cultural domain as well. Its publications, including the weekly Deshabhimani, were at various points edited and shaped by prominent literary figures, reinforcing the perception that the Left was not just a political formation but also a cultural movement. This historical proximity between the political and the intellectual created a tradition in which writers and thinkers functioned as fellow travellers—sometimes supportive, sometimes critical, but rarely detached.

It is against this backdrop that the current fissures acquire significance. The debate is not about an external intelligentsia challenging power from afar, but about voices emerging from within a long-standing ecosystem of ideological affinity.

Dr. T.T. Sreekumar, author and professor at the English and Foreign Languages University, Hyderabad, contests the logic advanced by those intellectuals who argue that electoral defeat is necessary to preserve ideological purity. In his view, the proposition that a return to power would automatically lead to the decay of the Left movement is analytically weak.

“It is illogical to suggest that winning again will necessarily erode the movement,” he argues. “One may raise specific political objections against the government—that is a different matter. I am not making a case for or against the Left returning to power. But to claim that defeat is essential to preserve moral high ground is fallacious at the outset.”

Sreekumar points to the broader national context. Kerala remains the only state where the Left retains substantive governing authority. If the Left were to be voted out there as well, he suggests, the symbolic and organisational consequences would be far greater than the hypothetical ideological ‘decay’ attributed to a third term.

Yet others interpret the present dissent not as abstract ideological reflection but as a deeply political intervention. Social observer and columnist Damodar Prasad argues that what critics describe as the government’s rightward drift and increasingly centralised style of functioning are widely perceptible. In that context, he suggests, silence from long-standing fellow travellers would have carried its own costs.

“Writers like Satchidanandan may have felt that if they did not articulate their differences now, their credibility would be at stake,” Damodar Prasad says. “There is a perception that the government is being influenced by right-wing logic. For intellectuals who have historically positioned themselves against such tendencies, remaining silent would have appeared inconsistent.”Intellectual dissent, in this view, is less about electoral arithmetic and more about safeguarding moral authority within a constituency that expects critical vigilance.The intervention of writers and cultural figures has undeniably added intensity to the early phase of the election campaign. Even if their distancing from the Left does not translate into measurable electoral shifts, it has furnished the opposition with ammunition.Whether intellectuals still possess the capacity to shape mass political behaviour—or whether their influence remains largely confined to elite discourse—remains an open question. What is clear, however, is that in Kerala’s politically literate society, the symbolic alignment or estrangement of its writers continues to matter, if not always at the ballot box, then certainly in the realm of political meaning.