For political prisoners booked under the stringent UAPA, prison experience reveals a daily reality of systematic deprivation

Often, there are no medical facilities inside prisons. Equipment and manpower shortages are rampant

In many prisons, prisoners working in medical facilities “treat” patients and prescribe them medicines

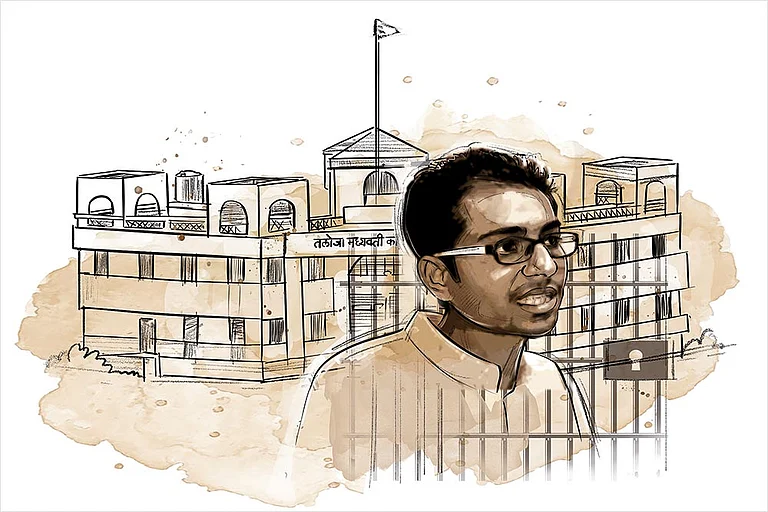

Mahesh Raut | A Broken Prison System Is In Dire Need Of Critical Care

Mahesh Raut, the youngest accused in the Bhima Koregaon case, was granted interim bail on medical grounds. Many prisoners have no hope.

What constitutes freedom? What does it constitute for the person who is confined or for the one who comes out of jail, only to get entangled in another web of chains; some similar, but for others, different from what they experienced behind bars. In a prison, your identity is reduced to just a number. You are dehumanised at the whims of authorities and burdened by numerous hurdles and difficulties to secure bail. Many are not able to come out of prison even after securing bail due to financial constraints. All these factors take a toll on the physical and mental health of prisoners.

Life outside prison does not let you come out of the cobwebs of the negative impacts on physical and mental health. For those who secure bail after years of incarceration, the transition often comes with crushing restrictions and social repercussions. They have to face stigma and hostility from neighbours and society at large. While reunion with family and loved ones is emotional, finding employment is a steep climb.

For the political prisoners ensnared in the Elgar Parishad-Bhima Koregaon Case, and for the other political prisoners, those who are implicated in cases under UAPA, India’s stringent anti-terror legal framework, the prison experience reveals a daily reality of systematic deprivation inside jail and a “liminal" freedom for those out on bail. I am yet to see the light of release on final bail in this matter—it’s been more than two years since the bail on merits was granted by the Bombay High Court, which subsequently got stayed and is pending for final hearing before the Supreme Court. Even though the stay on permanent bail is yet to be lifted, I got the opportunity to come out on interim bail four times during these two years.

This time, I came out on interim bail granted by the Supreme Court on medical grounds. In early 2025, I was diagnosed with two autoimmune diseases—Rheumatoid Arthritis and Sjogren's Syndrome, thanks to the prolonged incarceration. As my health situation worsened, and there was no adequate medical facility available in prison, I approached the Apex Court to seek relief. After going through the rigmarole of complicated procedures, I got interim bail in September 2025.

The time spent in prison after the diagnosis till I got interim relief was the period of continuous engagement, realisation of the situation of medical facilities or the lack of them in prison and also about the medical treatment of prisoners in general. There were some significant aspects to this; even though it was limited to interim bail, at least I was able to come out for medical treatment. But the opportunity I got is something that other prisoners never get. The situation in the prison is very bad; particularly in terms of health, medical conditions and mental health. There is total neglect of these serious aspects, both inside and outside of prison, as we see. But the basic minimum medical facilities in prison are also in a very bad state.

We know many stories wherein prisoners have lost their lives because they did not receive timely medical attention. We saw many prisoners perishing, dying a slow death. The hospital in prison is not equipped, neither in terms of infrastructure nor manpower. Equipment required for medical treatment are not available and if they are available, there aren’t enough trained people to operate them. There is a shortage of manpower; there aren't enough qualified doctors. The doctors who come there are in a hurry to leave. Often, medication is administered by prisoners who work in hospital as helpers. In effect, prisoners are running the hospitals on their own, relying on whatever medicine are available.

The dispensing of medicines for common ailments is normally done by prisoners and prison guards who work in the hospital and move from one barrack to another with a medicine box at night. They listen to the health problems of prisoners and make their own diagnosis, often based on common sense, and not tests and prescribe medicines. Often, the medicines are the same for all kinds of health problems, as limited medicines are available. In the absence of a proper medical diagnosis, treatments don’t start on time. Prisoners are given antibiotics and painkillers and sent back. In case of serious ailments, they are sent to government hospitals outside.

These hospital visits are based on the whims of the prison administration. Poor prisoners slip through the cracks. Only those who have resources and money, or those with whom the administration does not want to get into a confrontation, are sent to outside hospitals. Many prisoners, even those who are suffering from serious ailments, don’t end up in hospitals for treatment. Often, it’s too late.

Many die inside prison, many on the way to hospitals and some in government hospitals outside. Father Stan Swamy, our co-accused in the BK case, an 84-year-old Jesuit priest with Parkinson’s, was denied a sipper to drink water for weeks, not given timely medical treatment, and was sent to the hospital only after court intervention, which was very late, before his death in custody in July 2021. The issue of Father Stan’s institutional murder was raised and protested by many individuals and groups. It was widely reported in the media.

I recollect a situation when I was admitted to the hospital prison. A middle-aged prisoner was admitted in the middle of the night with a complaint of chest pain. No doctor visited him at night. He was in a lot of pain. We raised an alarm, told the guard to call for a doctor, but nothing happened and we were told to wait till morning. But in the morning hours, the person died while we were holding him. There was sadness and anger.

When it comes to timely medical care, I've had some luck. I owe it to the untimely death of Fr. Stan. The outrage it created had a cascading effect. Because of our case, I received attention. For me, it was an arduous struggle to hold on to hope that I would be able to make it this time. The diagnosis of the autoimmune diseases was delayed. It was actually an accidental diagnosis. The possibility of my having contracted these diseases earlier cannot be ruled out because there was no room for a proper diagnosis inside the prison facility. I was only able to get tested because of severe pain, and even that was done after I repeatedly requested and put pressure. Even after the diagnosis, I had to go through the legal route to get timely medical treatment. I never lost hope in these trying circumstances, thanks to the constant pressure, support of lawyers and well-wishers. I knew that I would survive this moment to fight for another day. I was determined, though this period (the last two years) has been very difficult. That for someone who has been granted bail to still find himself behind bars for more than two years just to vacate the stay in itself can contribute to serious health issues (often stress-based).

It's no more a personal/individual question, but a sad reflection of the long and winding road of the process, as inherent factors in the steep climb for judicial remedies in our criminal justice system. And even now, the inability to get relief in this way, regarding the ongoing process related to health and treatment, is an added pressure. When I was in prison, at least I was taken to the hospital, and finally after a long wait, I could get interim bail for medical treatment. But this is not the situation for other prisoners. There is no concern for the health of prisoners, those who have already been subjected to rejection by society. The prison system treats them even more poorly and doesn't allow them to go where they need for timely medical treatment. The rapid deterioration, from relatively good health to deep distress to a life-threatening situation and even death, is a process I was often witness to during my period in prison. So many untold stories of prisoners who die slow death in prison.

Prisons reflect our society, institutionalising and perpetuating injustice—social, economic, political inequalities. The marginalised people are left behind in India’s criminal justice system as it has a disproportionate impact on people belonging to minority, Dalit, Indigenous communities. Denial of timely medical care and total medical negligence in prison is used by the state as one of the tools in its long list of retributive tactics. Hence, inside or outside the prison, “freedom is an illusion”, until the prison and other institutions and structures of oppression and exploitation are dismantled.

Violence erupted on January 1, 2018, during a Dalit commemoration of the Battle of Bhima Koregaon’s 200th anniversary, resulting in one death and multiple injuries from stone-pelting and arson. Tensions stemmed from caste hostilities, with the speakers at the Elgar Parishad event probed for incitement. Investigators named several activists in connection with the Elgar Parishad event. The celebration commemorates the 1818 battle, seen as a symbol of Dalit resistance. Key arrests included Sudhir Dhawale and Jyoti Jagtap, followed by activists such as Surendra Gadling, Shoma Sen, Mahesh Raut, Rona Wilson, Sudha Bharadwaj, Arun Ferreira, Vernon Gonsalves, Varavara Rao and Gautam Navlakha.