MGNREGA altered the citizen-state relationship in rural India. It gave workers leverage—against landlords, contractors, and local officials.

Women, in particular, used the programme to negotiate wages and mobility. The retreat from a rights-based framework erodes this leverage, returning workers to precarity.

The ideological migration—from right to scheme—reshapes accountability, weakens the worker’s claim on the exchequer, and alters the grammar of social citizenship itself.

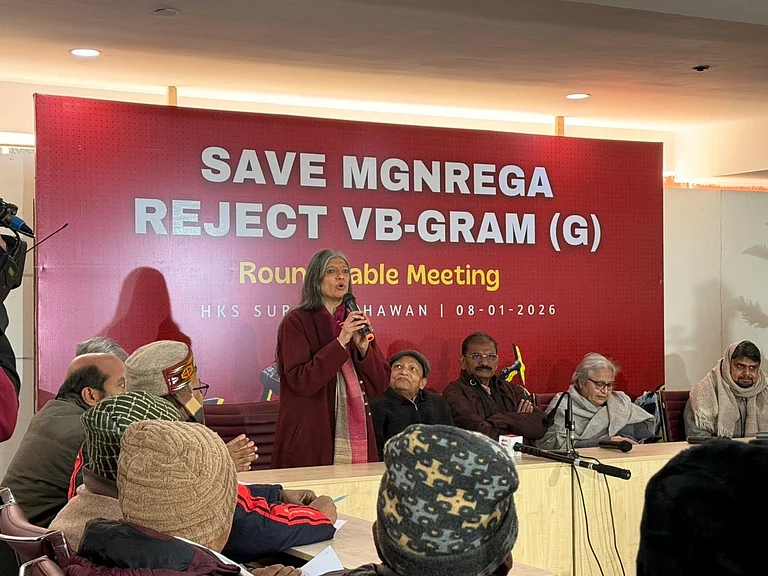

Gandhi To Ram: Dismantling Of MGNREGA And Rewriting Rural Welfare

The dismantling of MGNREGA is not a technocratic policy decision but a logical extension of a political project that is uneasy with enforceable rights—especially when claimed by the poor

The dismantling of MGNREGA and the enactment of VB-G-RAM-G represent more than the closure of one programme and the birth of another. They signal a transformation in how the Indian state interprets its obligation to the rural poor. Where the original Act located poverty in the structural absence of dignified employment and responded with a demand-driven, legally enforceable guarantee, the Ram-named successor shifts the axis to administrative management. Work is no longer something a citizen can

compel; it is something the state may provide. This ideological migration—from right to scheme—reshapes accountability, weakens the worker’s claim on the exchequer, and alters the grammar of social citizenship itself.

MGNREGA, enacted in 2005, was an anomaly in post-reform India. Emerging from sustained mobilisation by grassroots movements and policy advocates, it treated unemployment as a structural failure rather than an individual deficit. Its most radical feature was not the number of person-days it generated, but its legal architecture: demand-driven employment, time-bound guarantees, unemployment allowances, social audits, and that fact that it was fully litigable. Several activists and labour economists point out that the contribution of MGNREGA to social justice went beyond its role as an anti-poverty tool.

The Act empowered the poor. For the first time, rural Indians could legally compel the state to act. As the social scientist and welfare economist Jean Drèze said: “MGNREGA gave some bargaining power to rural workers. For instance, many bonded labourers have used MGNREGA as an escape from slavery. Similarly, MGNREGA empowered rural women by giving them a rare opportunity to earn their own income in a dignified manner. Further, MGNREGA helped unorganised workers to organise. Where this happened, it was a truly liberating experience for many.”

That premise has now been abandoned. The replacement framework shifts employment from a right to a scheme—one mediated by administrative discretion rather than citizen

entitlement. The change reveals a deeper transformation in the state’s theory of poverty: from a condition requiring enforceable guarantees to a problem to be managed through calibrated welfare delivery.

Reduced Poverty, Prevented People from Falling Below the Poverty Line

MGNREGA had a measurable impact on incomes among the poor. It provided predictable employment and cash income, reduced dependence on informal lenders, supported rural wage levels, and generated tangible welfare gains. For millions of households facing chronic underemployment and seasonal distress, the programme functioned as a safety net, income stabiliser, and poverty-alleviating institution. The quantitative evidence points to significant poverty reduction, increased consumption, and improved economic resilience where the scheme was implemented effectively.

The law, now repealed, reduced poverty by up to 32 per cent and prevented about 14 million people from falling below the poverty line in its first decade of full implementation, according to an analysis of national data.

A study by the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative found that income from MGNREGA work increased per capita consumption by roughly seven per cent of the national poverty line in regions where the programme was strongly implemented, indicating real increases in household welfare and consumption capacity.

MGNREGA quickly became one of the world’s largest public employment programmes. By the early 2010s, millions of rural households were participating: one evaluation found that by FY 2010–11, the programme had provided employment to about 5.47 crore rural households, generating roughly 256.44 crore person-days of work nationally.

The scheme particularly benefitted traditionally marginalised groups and women. In many years, more than half of the workforce under MGNREGA has been women, helping boost their incomes and bargaining power within households and communities.

By offering work during the agricultural lean season—when farm labour is scarce and wages are lowest—MGNREGA provided a crucial safety net that helped rural families avoid distress coping strategies such as high-interest borrowing. Multiple impact assessments report reductions in household debt levels and a decline in dependence on informal moneylenders where the programme was effectively implemented.

Beyond direct income, the programme contributed to improved food security and reduced seasonal migration. Case studies indicate that in some districts, MGNREGA employment opportunities helped reduce seasonal labour migration to cities, keeping families more stable and connected to local agricultural cycles.

MGNREGA’s guaranteed wages were often used by families to invest in children’s education, health expenditures, and basic consumption, contributing to long-term human development

outcomes. Though comprehensive national longitudinal data is limited, localised studies show increases in school attendance and consumption correlated with secure MGNREGA income.

MGNREGA Was Politically Inconvenient

MGNREGA created inconvenience by design, said one government official who was involved in early evaluations of MGNREGA. “It forced the state to respond to demand, not convenience.” This friction is precisely what made the programme politically inconvenient, and hence it became crucial to make the law ineffective—a process that was carried out gradually.

Over the past decade, successive changes hollowed out the Act: delayed wage payments, shrinking budgets, digital attendance systems that excluded workers, and the quiet erosion of unemployment allowances. The final step—replacing the programme altogether—completes the transition.

Former senior officials in the Rural Development Ministry describe the new model as administratively streamlined. But activists argue that efficiency has become a euphemism for control. Without the threat of court intervention, grievance redressal collapses back into bureaucratic channels where power asymmetries are entrenched.

The consequences extend beyond wages. MGNREGA altered the citizen-state relationship in rural India. It gave workers leverage—against landlords, contractors, and local officials.

Women, in particular, used the programme to negotiate wages and mobility. The retreat from a rights-based framework erodes this leverage, returning workers to precarity.

The most scathing critique has come from people like Drèze, who witnessed how MGNREGA transformed the lives of the rural poor. In an interview with Outlook, he said that the government is promising jobs without guaranteeing work. He also highlighted that, by repealing MGNREGA, the government prioritised the concerns of the Centre over those of the rural poor. The law has been recast as a discretionary, centrally controlled scheme with budget caps, blackout periods, and political gatekeeping.

Under the VB-G-RAM-G Act, the Centre has all significant powers and no significant obligations. “The Centre has no reason to bother with employment guarantee since the obligation to meet the demand for work lies with the state governments. It can treat VB-G-RAM-G like any other centrally sponsored scheme. Worse, it can restrict this scheme to notified areas of its own choice,” he said.

From Gandhi to Ram: The Politics of Naming

The ideological shift is also visible in language. The decision to replace “Mahatma Gandhi” with “Ram” in the naming of the rural employment programme has been widely dismissed by government spokespersons as cosmetic. But in a polity where symbolism does heavy ideological lifting, names are never neutral. They signal lineage, moral authority, and the philosophical foundations of policy.

MGNREGA drew legitimacy from Gandhi’s association with the dignity of labour, village self-rule, and the ethical obligation of the state to protect the poorest. The name anchored the law in a rights-based tradition that linked citizenship to entitlement, not cultural identity. Its removal is therefore not incidental; it marks a deliberate rupture with that legacy.

“Ram”, as deployed in contemporary political discourse, is not merely a religious figure but a civilisational signifier—one increasingly mobilised within a majoritarian framework. By attaching welfare to this symbolism, the state reframes social protection not as a constitutional right but as moral benevolence embedded in cultural nationalism. Welfare becomes something bestowed, not claimed.

This shift matters. Rights-based laws invite scrutiny, audit, and litigation. Culturally coded schemes invite gratitude and loyalty. The repeal of MGNREGA thus tells us that the Indian state is increasingly uncomfortable with rights that can be invoked by the poor against power. It prefers welfare that can be administered, branded, and controlled.

Governance Framework Centred on Duties

But if one analyses the Modi government closely, the repeal of MGNREGA and the shift from a rights-based framework to a discretion-driven scheme does not come as a big surprise. It aligns closely with the ideological direction articulated repeatedly by Narendra Modi in recent years.

In speech after speech, the Prime Minister has foregrounded fundamental duties over fundamental rights, recasting citizenship less as a relationship of entitlement and accountability and more as one of obligation, discipline, and compliance.

This rhetorical shift is not incidental; it signals a deeper reorientation of the state’s vocabulary. Rights-based welfare regimes like MGNREGA presume a citizen who can make claims against power—who can demand work, seek legal remedy, and hold the state accountable for failure. A governance framework centred on duties, by contrast, places the onus on citizens to prove worthiness before assistance is extended. In such a worldview, welfare is no longer something owed as a matter of justice, but something granted conditionally, mediated by administrative discretion and moral judgement.

Seen through this lens, the dismantling of MGNREGA is not a technocratic policy decision but a logical extension of a political project that is uneasy with enforceable rights—especially when claimed by the poor. The retreat from guaranteed employment mirrors a broader discomfort with constitutionalism as a rights-bearing compact, and its replacement with a model of governance that prizes obedience, productivity, and cultural conformity over legal entitlement. In this India, the citizen’s duties are loudly proclaimed, while the state’s obligations are quietly withdrawn.

Tags