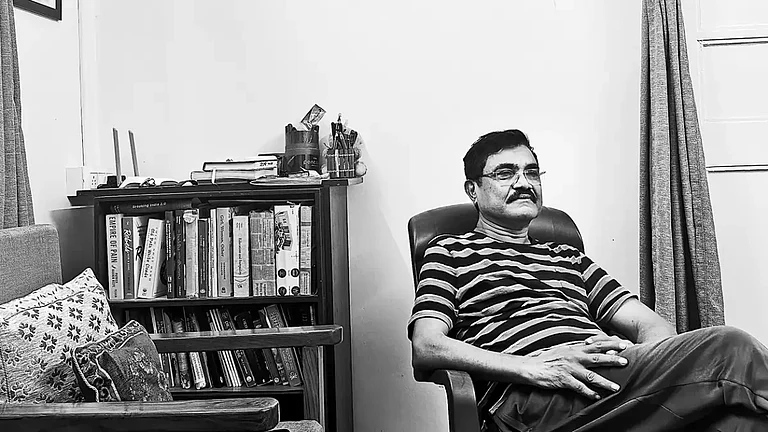

Anand Teltumbde’s latest book is The Caste Con Census.

In the book, Teltumbde argues that caste is not a list of categories waiting to be counted but a graded hierarchy that governs access to dignity, education, land, labour, and power.

Teltumbde critiques sub-categorisation as a narrow administrative fix that fragments oppressed groups further without addressing the real problem: unequal capacity-building and limited opportunities.

The Caste Con Census: Why Counting Caste May Wound More Than It Heals

Anand Teltumbde’s deeply researched book challenges the popular belief that a caste census will advance justice, arguing instead that enumeration can entrench caste consciousness and shrink the terrain of real equality.

Anand Teltumbde’s The Caste Con Census arrives at a moment when the country is loudly debating the need to “count caste.” But the book does not simply join this debate; it rewires it. With remarkable clarity and intellectual honesty, Teltumbde shows that a caste census is never an exercise in neutral measurement. It is an act that reshapes the very society it claims to describe. The book warns that enumeration, especially of caste, is always political, always consequential, and often far more dangerous than its proponents admit.

What distinguishes this book from the noise surrounding the caste census is its refusal to treat caste as a technical or administrative problem. Teltumbde insists that caste is not a list of categories waiting to be counted; it is a graded hierarchy that governs access to dignity, education, land, labour, and power. The contemporary discourse, he argues, has shrunk this vast moral and structural reality into the small frame of quota arithmetic. The caste census is widely spoken of as a tool to recalibrate reservations, but almost never as an instrument that could amplify caste consciousness and deepen divisions.

The book’s historical excavation sets the tone. Teltumbde meticulously traces how colonial censuses did not merely record caste—they solidified it. What were once fluid, localised, and context-dependent identities became rigid, pan-Indian formations under the classificatory regimes of six decennial enumerations. The British found in caste a perfect technology of governance: a way to divide a politically awakening population after 1857, and to anchor power through careful fragmentation. This colonial logic, the author argues, was not dismantled in 1947. It was inherited, preserved, and sharpened by the postcolonial state.

One of the book’s most unsettling insights is that India had the opportunity to abolish caste when it abolished untouchability. The Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes were, after all, administrative labels — not theological realities. But instead of breaking the back of the system, the new state expanded reservation to the “Backward Classes” on the vague and manipulable criterion of “social and educational backwardness.” In Teltumbde’s reading, this was less a gesture of justice and more a political act designed to maintain caste as a central organising principle of electoral life. The result was a caste cauldron that would simmer endlessly.

Its consequences are visible today. As public-sector jobs shrink under neoliberal reforms and education becomes increasingly privatised, the terrain on which reservations can deliver mobility is shrinking. Yet demands for quota expansion have multiplied, driven by intra-group resentment and elite capture within Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and OBC groups. Teltumbde’s chapters on the myth of caste homogeneity and internal stratification are some of the sharpest pieces of sociological writing in recent memory. He shows how large clusters like SC, ST, and OBC are themselves deeply unequal, with dominant sub-castes cornering benefits while the most deprived remain invisible.

This is where the book breaks new ground. Instead of advocating sub-categorisation—now a fashionable policy response—Teltumbde critiques it as a narrow administrative fix that fragments oppressed groups further without addressing the real problem: unequal capacity-building and limited opportunities. His alternative, the Reservation Usage Score and Dampening Factor, offers a strikingly pragmatic framework. It recognises that reservation benefits accrue to individuals and families, not entire castes, and seeks to distribute opportunities more equitably without reinforcing caste identities. It is rare to see a thinker who combines structural critique with a mathematically coherent proposal.

But the book’s most provocative turn comes in its analysis of contemporary politics. Teltumbde argues that a caste census is unlikely to weaken ruling parties; if anything, it may strengthen them. The lower strata of the backward castes — a key segment of the BJP’s social base — may interpret enumeration as acknowledgment, deepening their emotional alignment with the party. Meanwhile, the exclusion of the “general category” from caste enumeration provides fertile ground for expanding the EWS quota, slowly shifting India from caste-based reservation to economic-weakness-based frameworks. Enumeration, in other words, could become the Trojan horse for dismantling the very idea of caste-based affirmative action.

The final chapters are the book’s philosophical heart. Teltumbde argues that annihilation of caste must remain the ultimate horizon of any politics claiming to be just. Yet he admits that today’s climate — where even caste’svictims mobilise it as a resource — makes this goal feel distant. Still, he insists that without universal capacity-building — quality education, healthcare, land redistribution, secure livelihood, and equal starting conditions — reservation will never achieve its transformative purpose. It will simply manage inequality instead of dismantling it.

What elevates The Caste Con Census is not only the sharpness of its arguments but the moral seriousness with which they are made. The book is deeply researched, historically grounded, and written with an arresting clarity that cuts through the fog of policy chatter. It does not flatter its readers. It challenges them to confront uncomfortable truths: that caste cannot be counted without being strengthened; that political elites have preserved caste even while claiming to undo it; that reservation without universal social rights risks becoming a ladder for a few, not a bridge for all.

At a time when political discourse celebrates data without scrutinising its power, this book is a necessary intervention. It reminds us that enumeration is not a mirror but a tool — and tools can liberate, or they can wound. Teltumbde warns that the caste census, far from being a pathway to justice, may deepen the architecture of caste if pursued uncritically.

In the end, The Caste Con Census is not a book about counting bodies. It is a book about counting the cost of letting caste define our future. Its power lies in its clarity, its courage, and its insistence that justice requires far more than measurement — it requires imagination.

Sahil Hussain Choudhury is a lawyer and Constitutional Law Researcher based in New Delhi.