The moment before making a mark is where memory and imagination merge, forming the emotional source of the artist’s visual thinking.

Imagined landscapes are shaped by fragments of lived memory, inherited stories, and sensory recall, blurring the line between what is remembered and what is invented.

Drawing on A.K. Ramanujan’s thinai concept, landscapes function as emotional codes, where terrain, colour, and horizon express specific states of longing, loss, and possibility.

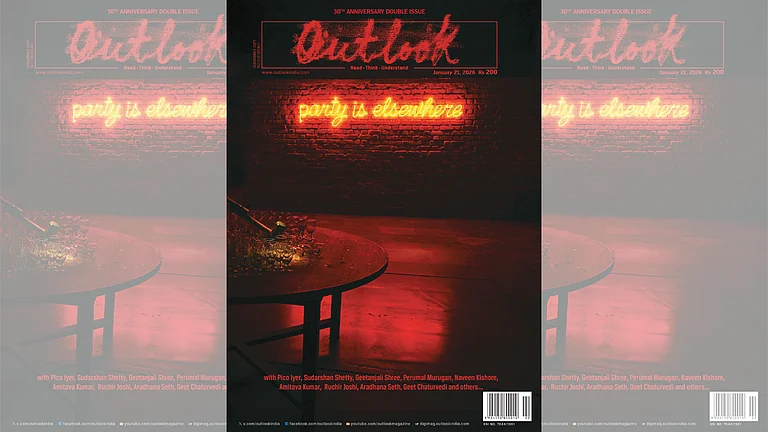

Outlook Anniversary Issue: Visualising Fictional Landscapes

A fictional landscape trembles at the edge of sight. It has not yet become a line, or a stroke of colour, it just exists as a pressure behind the eyes, like a thick fog looming over an uncharted river.

Is a Delhi-based curator, writer, and filmmaker dedicated to an intellectually rigorous and politically informed engagement with contemporary art. As a curator at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, he is committed to bridging the gap between art and the public

The moment is suspended in the silence before the first mark is made. A fictional landscape trembles at the edge of sight. It has not yet become a line, or a stroke of colour, it just exists as a pressure behind the eyes, like a thick fog looming over an uncharted river, like a hint of shadow across the plaza where no footsteps echo. Imagination lingers here for the visual artist. This is the private corner of visual experience where imagination fractures and reforms. It is as if one has glimpsed these spaces in some half-remembered past, though one knows with surety, they have never been visited. Indistinguishable from one another, memory and imagination warp here.

The artistic imagination does not draw from a void but from the already seen shards of lived realities recombined until estrangement and recognition coincide. The rainy courtyard glimpsed in childhood; its architectural structures slowly dissolve into the memory of a shoreline seen only in photographs. The red earth of tilled farmlands transforms fluidly into the flank of a gigantic mountain. Overheard conversations from a journey, evening in forgotten cities, inherited stories passed through generations of telling until their origins remain a mystery.

A. K. Ramanujan, that meticulous cartographer of the interior, understood this well. In his translations of ancient Sangam poems and extensive meditations on the classical thinai system (ecozones), landscape was not only a topography; the misty hills of Kurinji contain an emotional register within them, the trembling of hidden rendezvous, the ache of forbidden longing. The parched and desolate wastelands of Palai signify abandonment, of the emptiness one feels when one is left alone in that landscape. Each of these terrains bore its own afflictions, its own specific sadness or joy. When the artist imagines a landscape that has never existed, they too are plotting such a map, encoding within it the visible elements of an entire affective and temporal code. In this imagination horizon is not merely a line where earth merges with the sky, but also becomes an expression of limits or possibilities. Colour becomes a language, the bleeding of light as Goethe said and the golden suffocation of nostalgia.

Artistic imagination starts its true negotiations when the hand must move. It is in these moments that Maurice Merleau-Ponty, the French philosopher, insists on the relevance of the embodied nature of perception. For Merleau-Ponty, the eye of the painter is not a separate apparatus, like a camera that passively records what comes before it. Instead, the eye is part of the entire body’s engagement with the world. It is a lived body that is already entangled in the textures and perspectives of existence. When the hand finally moves, the artist makes that first mark, where the charcoal touches the paper, the brush encounters the surface, a strange miracle happens. The vivid inner image begins to dissolve, but the lines defy.

The paper’s grain, canvas’ surface, resists the transfer. The pigment accumulates more heavily than once thought or thins to transparency. An intense conversation between intention and the restrictions of material, between what the artist imagined and what the world, through its stubborn resistance, allows. What begins as a straight path in the mind, guided by the body, the limbs, curves towards the destination the artist did not consciously plan. The painting process of the body attempts to visualise what the imagination of the mind explored. Not being able to match that is not a failure of the body, but it is instead the inherent tension of making. The slow arrival of the image through the act of rendering imagination, in which each mark constrains and enables the next. Decisions impact the next steps. The emerging landscape slowly begins to possess its own logic; the image insists on how it must be arranged.

Marks and signs begin to accumulate, while the invented place claims its logic. Scale announces intent, vast architectural fragments assemble, populated by lonely silhouettes where the horizon in twilight forms the background of a frame. Light reveals its character, merciless skies shower brutal revelation, and an eternal apocalypse blurs the edges into reverie. Colour marks the time; the textures of the strokes pulsate in this imaginary landscape, and a fictional atmosphere emerges. Novelist Orhan Pamuk echoes this process in his The Museum of Innocence, which is a spatial and visual reimagining of the spectral Istanbul through his protagonist. He obsessively collects fragments of his lost beloved, such as cigarette stubs, a single earring, and old photographs. The novel and the museum do not illustrate each other; instead, they interpenetrate by deepening the other’s existence and meaning in a conflictual relation. The objects in the museum make tangible the novel’s emotional and historical contexts. It becomes an object-oriented narrative through a layering of memory, imagination, and material culture. Artistic visualisers do something remarkably similar, despite the difference in materials. They visualise absent rooms, inaccessible chambers, framing the unfathomable realities so that they return to haunt what is visible.

But here is a paradox that is essential to the artwork: no image can be complete. Roads must stretch beyond the edges of the frame. Windows open onto invisible spaces. Horizons are drawn, suggesting vast terrains that remain unseen. This incompleteness is not a limitation but a form of artistic generosity that invites the viewer to be the co-creator. They fill the gaps with their own interior images, their own memories, and desires. A viewer, while looking at an imagined city, may identify in its contours the homeland they left behind. Another may see in its spaces the premonition of a cataclysm yet to come. The image is the isle where the private imagination and the collective history intersect. The hand lifts, the image remains, mute yet voluble. By visualising the unseen, the artist redraws our world, affirming, amid silenced discourse, that seeing otherwise tolerates. When words fail, vision persists as fidelity to the imaginable: a lantern against invading night, proof that even skies welcome other dawns.

(Views expressed are personal)

This article appeared as Visualising Fictional Landscapes in Outlook’s 30th anniversary double issue ‘ Party is Elsewhere ’ dated January 21st, 2025, which explores the subject of imagined spaces as tools of resistance and politics.

Premjish Achari is an art curator, writer and filmmaker. His creative pursuits constantly attempt to disentangle the new visual regime we are caught up in