Arun Ferreira describes illegal detention and the fear of being killed in a fake encounter.

The memoir details custodial torture designed to leave no visible injuries.

Police allegedly fabricated evidence and charges under the UAPA to justify arrest.

Book Excerpt: Colours Of The Cage: A Prison Memoir, By Arun Ferreira

In May 2007, human rights activist Arun Ferreira was arrested by the Nagpur Police on charges of being a Naxalite. This book is a stark and unsparing account of the nearly five years that he spent in jail

I was afraid they’d kill me. Thus far, there was nothing official about my detention. They hadn’t shown me a warrant, nor had I been taken to a police station. I feared that the police could murder me and pretend that I’d been killed in an encounter. I’d read about many situations in which the police claimed to have had no option but to open fire when suspects they were attempting to arrest had resisted. I knew that the National Human Rights Commission had noted thirty-one cases of fake encounter killings in Maharashtra alone in the previous five years. The physical torture, though painful, was relatively tame compared to this prospect.

At midnight, eleven hours after I had been detained, I was taken to a police station and informed that I had been arrested under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 2004, which is applied to people the state brands as terrorists. I spent that night in a damp cell in the station house. My bedding was a foul-smelling black blanket, so dirty that even its dark colour could barely conceal the grime. A hole in the ground served as a urinal. It could be identified by the mass of paan stains around it and its acrid stench.

I was finally served a meal: dal, rotis and abuse. It wasn’t easy to eat from a plastic bag with jaws sore from the blows I had received earlier in the day. The only solution, I learnt, was to soften the rotis by soaking them in the bag of dal. But after the horrors I had undergone, these tribulations were relatively insignificant and allowed me a brief moment to pull myself together. I managed to ignore the putrid bedding, the humid air and the ache in my body and dozed off.

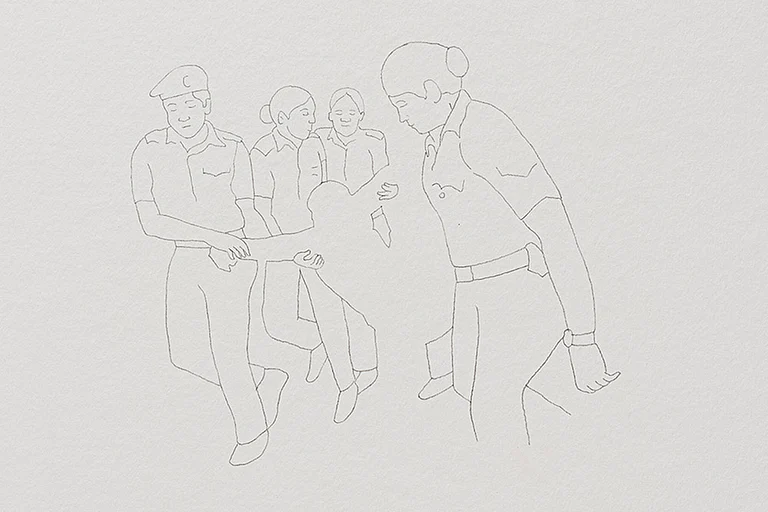

Within a few hours, I was woken up for another round of questioning. The officers appeared polite at first but quickly resorted to blows in an attempt to encourage me to provide the answers they were looking for. They wanted me to disclose the location of a cache of arms and explosives or information about my supposed links with Maoists. To make me more amenable to their demands, they stretched out my body completely, using an updated version of the medieval torture technique of drawing (though there was no quartering). My arms were tied to a window grill high above the ground while two policemen stood on my outstretched thighs to keep me pinned to the floor. This was calculated to cause maximum pain without leaving visible injuries. Despite these precautions, my ears started to bleed and my jaws began to swell.

In the evening, I was forced to squat on the floor with a black hood over my head as a posse of officers posed behind me for press photographs. The next day, I would later learn, these images made the front pages of newspapers around the country. The press was told that I was the chief of communications and propaganda of the Maoist Party.

I was then produced before a magistrate. As all law students know, this measure has been introduced into legal procedure to give detenues the opportunity to complain about custodial torture—something I could establish quite easily since my face was swollen, ears bleeding and soles so sore that it was impossible to walk. But from the deliberations in court, I gathered that the police had already accounted for the injuries in the story they’d concocted about my arrest. In their version, I had fought hard with the police to try to avoid capture. They claimed they had had no option but to use force to subdue me. Strangely, none of my captors seem to have been harmed during the scuffle.

That wasn’t the only surprise. In court, the police said that I’d been arrested in the company of three others—Dhanendra Bhurule, a journalist with a Marathi daily called Deshonnati; Naresh Bansod, the Gondia district president of the Maharashtra Andhashraddha Nirmulan Samiti (Maharashtra Superstition Eradication Committee); and Ashok Reddy, a former trade union organizer from Andhra Pradesh. The police claimed to have seized a pistol and cartridges from Ashok Reddy and a pen drive containing seditious literature from me. They said we had been meeting to hatch a plan to blow up the monument at the Deekshabhoomi in Nagpur. This is the spot where the Dalit leader Dr Bhimrao Ambedkar and more than 300,000 of his followers had converted to Buddhism in October 1956, seeking to liberate themselves from Hinduism’s oppressive caste system. By manufacturing a plot to show that leftists had been planning to attack the hallowed Ambedkar shrine, the police were obviously trying to drive a wedge between Dalits and Naxalites.

But mere allegations would not be sufficient. They needed to create evidence to support their claims. The police told the court that they needed us in custody for twelve days to interrogate us. While Dhanendra Bhurule and I were kept in the Sitabuldi police station in Nagpur, the other two were taken to the Dhantoli police station. Dhantoli was the station in Nagpur where the case had been formally registered. Twice or three times a day, a constable would come to my cell to fill in the official records: ‘Naam? Baap ka naam? Pata? Dhanda?’ (Name? Father’s name? Address? Occupation?) As he went through the routine with the man in the next cell, I realized that it was occupied by Bhurule, the journalist from Gondia, who had been accused in the same case as I was. We began to exchange a few words at mealtime.