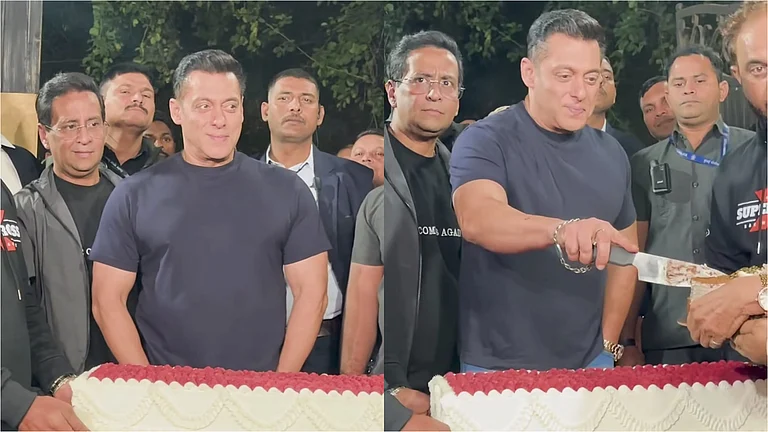

December 27 marks Bollywood star Salman Kan's 60th birthday.

Breaking out as a romantic hero in Maine Pyar Kiya (1989), a slew of hits in the 1990s established him as a box-office rage.

In the last six years, however, Salman’s stardom has turned deeply vulnerable.

Salman Khan At 60: Inside The Unravelling Of Bollywood's Once-Invincible Superstar

In the Khan-trio, Salman’s superstardom has frayed the most.

Salman Khan’s stardom is embedded in the goodwill he has amassed. The unbending charitable zeal his persona wields goes with it. No matter the widely documented accounts of unprofessionalism and abusive behaviour, the fraternity swears by his impeccable niceness. Everyone sings paeans to his loyalty and philanthropy with the Being Human foundation. Despite horror stories about his infamous rages, mood swings, criminal cases slapped for hit-and-run and poaching, his fanbase has remained steadfast for the longest time.

Breaking out as a romantic hero in Maine Pyar Kiya (1989), his upsurging move seemed destined. A chocolate-boy image endeared him immediately to the audience. A slew of hits in the 1990s, like Hum Aapke Hain Koun..! (1994), Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam (1999), Andaaz Apna Apna (1994), Judwaa (1997), Biwi No.1 (1999), established him as a box-office rage. However, his ascendancy did have its uneven path—a string of flops especially in the early 2000s. By then, Shah Rukh Khan already had a smooth journey, which would fall into a slump as late as the late 2010s. With Wanted (2009), Khan bounced back. Dabangg (2010) sealed his superstardom. His presence was lively, crackling, instantly garnering a new army of followers awed by a superstar taking shots at his image.

Khan appeals to the heart. That’s his mojo. Basic intelligence takes a backseat. There’s no attempt to be cosmopolitan and hip like Shah Rukh, or edge towards occasional experiments like Aamir Khan. One of his memorable lines in 2014’s Kick encapsulates his effect: “Mere bare mein itna mat socho. Main dil mein aata hoon, samajh mein nahin” (“Don’t analyse me so much—I win hearts, not the intellect”). Khan’s films ride on mass connect, while the urban middle classes are turned away in condescension. Working class and rural fans worship him as bhai. Unlike the others in the superstar-trio, Aamir and Shah Rukh, Salman hasn’t reflected any interest in pairing with the country’s foremost directors, or being backed by swanky production houses. In her article The irresistible badness of Salman Khan (2020), academic and filmmaker Shohini Ghosh writes, “A very large slice of Salman’s traditional fan-base is comprised of those for whom the changes unleashed by the forces of globalisation didn’t accrue any immediate benefits.” Salman’s star persona maps out a constant tussle between the Muslim identity and their existence within India’s rapidly far-right leaning, Hindutva fascist polity led by Narendra Modi and the BJP.

As the Hindu-Muslim bridge

Over the course of his career, he makes varied attempts to stitch the Muslim individual into the Indian social fabric, straining to make it an inveterate, easily-fitting part. He makes it a point to release his new films on Eid. Be it Bajrangi Bhaijaan (2015) or Sultan (2016), two of his biggest hits, they wrestle with Islamophobia and espouse a secular plea. As a result, his stardom crosses religious lines. There’s a lot of regard for the State. He’s the bhaijaan for both Muslims and Hindus. He isn’t dismissing a country mired in growing intolerance as much as he is widening space for the promised Hindu-Muslim amity. As Gohar Siddiqui underlines in his paper, Bridging the communal gap: The politics of Hindu-Muslim Salman Bhaijaan (2020), “Most of Salman’s characters are Hindu but they have a Muslim flavour, often indicated through cultural codes, mise-en-scène, or through references to Pakistan”. In Bajrangi Bhaijaan, his character grows from being wary of Muslims and Pakistan to eventually trusting their compassion.

His films don’t have complex configurations, rather simple-minded directions. Expect no nuance or shades of moral uncertainty. There’s an old-school brand of heroism at play—one that pummels enemies and is bursting with codified male honour-keeping. Moral dualities are uncomplicated, neatly demarcated. The actor’s characters are always out to nab the goons. The Salman-hero is pure-hearted, magnanimous and the sole ray of home in a persistently grim, doomed world. He plays fast and loose with the rules if it can get him to knock down the villain(s). As in his 2003 film Tere Naam, he may kidnap a woman whom he fancies, but will baulk from physically assaulting her. Before he’s about to hit her, he retracts and bashes himself. This drawing the line is propped up by the film as critical in distinguishing the kind of man the actor will embody. Above everything, he is respectful of women, never mind the publicly recorded instances of reprehensible behaviour off-screen. There’s barely been a compelling role for actresses in his films, but they—from Shilpa Shetty to Manisha Koirala—speak fondly of him. In a 2024 interview with Zoom, Koirala remarked, “He has spontaneity; there’s no pretence. Whatever he is, he shows.”

Actresses in his films have hapless fates or are entirely peripheral, a passing afterthought. The hero/Salman Khan inevitably swoops in to save the day. Occasionally, lip service to the female lead is done by handing her an action sequence or two. Katrina Kaif’s role as a Yash Raj’s first female spy lends her some latitude to flex stunts. It’s an aberration from the usual mould of the heroine in Khan’s films, suggesting newly granted agency and personality. Nevertheless, the Tiger franchise remains heavily pegged on him. He’s the one pulling it through globe-trotting and undercover missions. Kaif’s Zoya is more than competent, righteous in her own way, yet the narrative is careful to skew the relationship between spies of rival nations to Salman’s patriotic Indianness. However, there’s some relief in the two ultimately escaping both their countries and making their lives elsewhere, away from the stranglehold of jingoist demands.

In film after film, he essays the upright citizen. In a 2018 interview with Deccan Chronicle, he emphasised on how youths blindly emulate their beloved stars. This gives him an added sense of responsibility. “That’s why I decided never to play a villain on screen because people can get impressed by my actions,” he stated. His roles tinker with vigilantism aplenty. In another essay, Transfigurations of the star body: Salman Khan and the spectral Muslim (2022), Ghosh further writes, “The master trope of Salman Khan’s stardom is his ripped and six-pack muscular body. The body becomes, for the man, who has lost everything, the last surviving weapon in the battle against injustice.” As in multiple films like Garv: Pride and Honour (2004)and Tumko Na Bhool Payenge (2002), the enemy is communalism and majoritarian hate. Salman is a one-man army, paving the way for justice. He doesn’t actively reject religion; he only suggests peaceful recourse.

With the Tiger franchise, he’s ostensibly pushing for Indo-Pak camaraderie, while allowing India the moral upper hand by some degree, though the final impetus is to turn away from both nations.

Fractures in the Salman-myth

In the last six years, however, Salman’s stardom has turned deeply vulnerable. Post-COVID, his films, Radhe (2021) and Kisi Ka Bhai Kisi Ki Jaan (2023), bombed. Sikandar released on Eid, the festive day that is his lucky charm. With a reported budget of 200 crore, the film scraped a mere 21.6 percent occupancy on the first day. Ultimately, it collected just about a hundred crores. Karan Johar once remarked that Eid belongs to Salman Khan. At 60, however, Khan is faced with a desperate need to reinvent.

Instead, he is stuck in nursing his vanity, playing hyperactive, bulky men who’ll barely show vulnerability. Khan is too busy being an impossibly honed, granite-muscle slab. It’s the typical case of a once-reigning superstar fully consumed in his myth as unassailable, stuffing the same diet of comically disastrous films down his viewer’s throat. When a star keeps playing safe in film after film, the tide of popular favour stands endangered. It was only a matter of time before the audience began distancing themselves from ‘Bhaijaan’. In these last couple of years, Khan has almost entirely lost his spark, becoming something automated in cranking manipulative emotion and unpersuasive, painfully dull action.

Since the pandemic, the world has drastically changed. Viewing habits and patterns have undergone dramatic shifts. With the streaming platforms removing floodgates on access to other Indian languages and international series, the audience is a different beast. Theatres have even lesser room for small-budget titles, maximally reserved for juggernauts (Pushpa, K.G.F., RRR). While Khan’s films are also heavily bankrolled, they appear as bland reiterations of the same jaded syntax. Not that Khan ever summoned bristling nuance; but at least, he seemed to blaze through the screen in a supersized manner and reach out directly to his audience. Now, he comes across as trapped in lazy, uninspired repetition. Much like Ajay Devgn, his performances and persona reek of fatigue. The “zombiefication” of Khan is complete. Once again, many, like his Sikandar co-star Shahzad Khan, attribute his spate of flops to his generosity, that Khan is agreeing to certain films as favours to his friends. It’s all a smokescreen. This urgently calls for introspection—pained, but unavoidable. Nothing but freshly ignited artistic hunger for challenging, provocative roles can swivel his fate around and rewrite his stardom.