Bi Gan's Resurrection premiered at Cannes Film Festival 2025, where it won a special prize.

It mines decades of cinema history into a strange, endlessly mutating form.

Resurrection screened at the 31st Kolkata International Film Festival.

KIFF 2025: Resurrection Review | Bi Gan’s Dream Epic Is As Astonishing As Annoying

The Chinese visionary erects astounding sequences that raze themselves into memory but the saga can exhaust in equal measure.

Nothing can prepare you for the mobile mysteries in Bi Gan’s Resurrection, a six-part odyssey of strange diversions. This saga gets peculiar with every bend. The minute you find it settling into recognizable terrain, Bi recoils like an allergic reaction, enacting yet another formal shock. Resurrection crafts a deep, lush lull that’s simultaneously at odds with itself. As much as you could drift along, Bi reassembles the cards and resets expectations. Even the scaffolding is spare. Shu Qi essays one of the “Big Others” in charge of nabbing the “Fantasmas”—a group of people whose persistent dreaming throws time into chaos. Being a select few in the larger human race that’s ceded dreams in an immortal grip, the Fantasmas briefly live in their discrete vivid dream-worlds. The Big Others hunt them out to restore the order of the world.

Resurrection follows a Fantasmer (Jackson Yee) as he’s trailed by a Big Other across studio-like carapaces. Yee keeps flipping between disguises and personages across the chapters, while intermittently putting back on a monster’s bearings. In the film’s staggering half-hour prelude, the viewer is held hostage to a dizzying series of montages. The semblance of a doll’s house ambushes these frameworks. Resurrection is elaborately orchestrated—a hall of mirrors with elusive reflections. It demands marveling, but has little emotional call back. Structure has never seemed so opaque, so slight. Few things recur, like the rain drenching every track at a time.

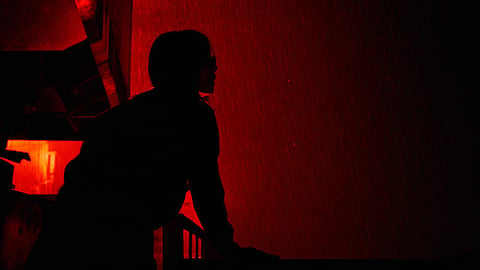

Suddenly, you’re hurled into a chilly spy noir, a mystery with an uncanny killer. The elegantly atmospheric section gathers tight intrigue, but this isn’t a film of resolutions. If motives of this couldn’t have been more obscure, Bi teases greater provocation in the next section—mischievous deities duping the unsuspecting near an abandoned Buddhist temple. This isn’t a filmmaker interested in holding onto a shot, no matter the intricate design, for too long. He wants to blow you away with razzle-dazzle, summoning the greatest reveries cinema is capable of. Hurry along, there are more jaw-dropping sequences down the road. Bi flirts with early animation techniques, a whole range of technical wizardry as has evolved across a century. He reserves the biggest stunner for the final stretch. In a single, unbroken take, Dong Jingsong’s camera shuttles across perspectives as it swoops on a vermillion light-soaked night—the closing one of the twentieth century. Reminiscent of the iconic oner in his earlier film, Long Day’s Journey Into Night (2018), Bi hits stronger notes here. Two strangers stumble into each other and are irresistibly magnetized by the other, but genre-inflected tragedy constantly defuses their union. Suddenly, tender melancholy sweeps up.

It’s all too much to process in a single viewing. Bi exhumes shifting histories, glancing through several cinematic modes to weave a fragmented fable. Resurrection changes shape, from silent-cinema throwback to yesteryear noir to vampiric hauntings, before you can pin it down into something legibly compact. Bi fashions a monument, cold to touch and striking sublimity—Liu Qiang and Tu Nan’s production design thrillingly matching every imaginative feat. To watch it is to be humbled.

Bi’s imagination is gargantuan, wildly unchecked—every moment a carefully designed disruption in contemporary movie-making. It’s one of those great experiments, whose potential failure is entirely secondary to the fact its maker has dared to leap so high. Where other storytellers might curtail themselves over practicalities, Bi’s images storm forth with defiant splendor. There’s no false modesty in him to diminish what he’s seeking to cobble together, neither any impulse to fit within convention. This is ambition of a different league altogether, barreling across stylistic dissonances to craft its own singular myth, seductive and distancing by turns. Bi keeps pushing at the edges of cinema, representability, how far and wide storytelling can approximate a world fantastically removed. In a later intertitle, Bi refers to the “forgotten language of cinematography”, directly jabbing at the monotonous contemporary sequence-mounting.

A film like this is bound to be frustrating. Resurrection occasionally glazes over with punishing indulgences. It grows airless, too consumed in self-admiration. Artifice is a tricky balance to strike, wavering between enchanting illusion and hyper-construction. Evoking awe over elevated sequences feels like such a continual duty for Bi that it veers into oppression—an imposition severed from charm. This is a film of excesses and its sensorial grandstanding alternately stuns and baffles. That Resurrection isn’t streamlined in any way both works its magic and spins stylized incoherence. You can either submit to its spell or be put off by showy tricks. It’s not so much about wrestling with the film’s fluid rhythms as it insists on a half-active dream-state of witness. Scrounging precise meaning and intentionality off every scene is relative, dismissed, almost scorned. Characters don’t especially resonate beyond being mere puppets at a vast theatre. Emotional comprehension itself is kept at bay. When Bi verges close to it in a later chapter, involving a kid trickster and a bereaved mobster, it feels too trite. Mercifully, Bi switches to a gorgeous, bittersweet, doomed vampire romance that pulls Resurrection out of a slump and bestows it with aching fragility.