The error was...it failed to take into account what the policies of liberalisation would do to a (middle) class which was morally rudderless...and socially insensitive to the point of being unconcerned with anything but its own self-interest.

—-Pavan K. Varma in, The Great Indian Middle Class

This idea was born over a few glasses of beer. Relaxing at a pub in PVR Saket in Delhi with friends, I noticed something odd. It was a group sitting at a corner table. It wasn’t the usual crowd you see in pubs. They were not zippies or yuppies, neither did they belong to the rich or the upper middle class. They didn’t belong to any elite sections like politicians, businessmen, or professional services like medicine, engineering or theIAS. Clad in simple and non-stylish attire, their demeanour suggested they were visiting the place for the first time. The trio represented the real middle class.

Bingo! That’s when it struck me that the India around me had changed. Especially Middle Class India. The myriad faces of pubs, malls, discotheques, bowling alleys,PVRs, flashy restaurants and exotic tourist locations had been transformed in the last ten years. No longer were these spaces restricted to the social and the economic elite. The actual—what you may term ordinary—middle class had now comfortably occupied these geographies. More than that, hanging out at these hitherto restricted, hallowed places had altered and mutated its mindset and attitudes. Or vice versa.

Just to be sure, I talked about the idea to friends and colleagues. Their reactions shocked me. "That’s me," said one. "Almost everyone I know fits the new middle class image that you have sketched," said another. A colleague wrote a passionate e-mail describing how the change was happening in her extended family of cousins. It seemed as if this was the right time to make my journey into the hearts and minds of this neo-middle class, this NMC.

Not that others haven’t written about it. Books like Gurcharan Das’ India Unbound and Pavan Varma’s The Great Indian Middle Class have captured some of these changes. But the problem with them was that they tried to paint it in black and white, as either good or bad. Both the authors also looked at the issue through the prism of economic reforms and unbridled consumerism. While Varma did talk about the historical reasons that prompted this unimaginable transition, he didn’t establish the new ingredients that helped make the middle class’ life more spicy and tangy, even pungent to an extent.

Moreover, I wanted to talk about this change through people, through those who have broken the traditional middle-class taboos, who behave in a clearly non-middle-class-ish way, who have done things that were unthinkable until a decade ago. After meeting dozens of them (with help from several colleagues), I realised that one was dealing with shades of grey. For one, many still believed that they were typically middle class, their basic values were still rooted in the old paradigm, although they may have done a few things differently. Others felt that there were many facets to this swarm of teeming millions, and it was made of several subsets.

As sociologist Ashis Nandy puts it: "It depends on how you define this class.If you consider income levels, you may not get anywhere.But if middle class is someone who’s educated, has access to information, and reads papers, you’ll discover the change." Another sociologist-acquaintance concludes, "There’s one middle class that’s bubbling with excitement, adventure andenthusiasm.There’s another that’s stricken by fear, anxiety and turmoil.You need to capture both." I also found people who encompassed both sets of emotions and weren’t sure who they really were except, possibly, the middle class. Still, there are some common sentiments and behavioural patterns that cut across the various segments that constitute the middle class.

- They have a certain consumerist streak and are obsessed with money.

- They have an individualistic tenor, with a heady cocktail of confidence, ambition, even brashness.

- They love (or aren’t scared of) risks.

- They are increasingly becoming depoliticised—some have never voted, others don’t care who’s in power, and many are only interested in issues that affect their immediate lives.

- They love their freedom and don’t care what the society thinks of them.

It’s not the MNCs, but the NMCs that’s taking over this country. It signifies the birth of, what I call, the The Great Indian Middle Sect.

The middle class, whose size is 250 million according to latest NCAER estimates, is on a shopping spree. And of those, 20 million households (or 100 million people) earn over Rs 2 lakh per annum, whose numbers will more than double by 2009-10, who will buy more consumer durables, two-wheelers and branded products. Last year’s survey byKSA Technopak felt that the size of only the urban consumers, including tweens (8-14 years) and teens (14-19 years), was nearly 100 million. It highlighted a new trend—the age at which people are buying assets like homes and cars is getting lower every year.

Nandan Nilekani, Infosys CEO, is best-placed to view this phenomenon as he keeps a close eye on the thousands of young techies at his campuses. "We got our first cars in 1989, eight years after we had started Infosys. Today, people buy cars and houses within years of service," he says. He adds that this is reflected in the increasing pressures on urban infrastructure. A decade ago, most migrants to cities were from the lower classes, who lived in slums or decrepit houses, never put pressure on amenities like water and power, and used public transport. Now, with the migration of the middle class, it creates traffic jams and has a multiplier effect on housing demand.

Look around and observe the mania. Meet Mr X, who manages the technical operations of a BPO firm, is married with a two-year-old kid, and whose father is a government employee. He’s taken a home loan, which he’s still repaying, and has no qualms about being saddled with more debt. He took a personal loan for doing his house’s interiors. He took another one to do a long-distance management course from Sterling University (UK). He paid that and went in for another one last year to holiday in London. He’s paid that too, but has taken a top-up loan to re-renovate his house. Obviously, he changes his mobile in months and he’s changed three cars in the last 10 years. "I’m not into irresponsible spending. But I live for the moment, I can’t wait for tomorrow, I want my needs to be fulfilled today," he feels.Ironically, as longevity increases every year, the middle class is more bothered about the present.

Taking risks partially stems from this uninhibited materialistic pursuit, apart from the unabashed urge to follow one’s passions.Chetan Bhagat, 31, anIIT graduate, is a successful investment banker, who works in Hong Kong for Deutsche Bank.But now, he wants to chuck up his job and become a writer after reasonable success with his first book, Five-point Someone, a fictional account of life at the IITcampus. "My second book (One Night @ The Call Centre) will be released soon. While the first one was personal and based on my own experiences, the second was written for professional reasons. If it does well, it might become a career option. I might move to Delhi and even explore writing film scripts," he reveals.

More importantly, Chetan feels that his success was so-lely because the Indian middle class has changed. "Ten years ago, no one would have read my first book, which was based on middle-class frustrations and aspirations. It worked only in 2004, when the values of this class have shifted, they don’t feel inferior to the West, take pride at being an Indian and want to read simple and interesting things about themselves." Even his decision to quit is timely in another sense. "My parents would have raised eyebrows if I had suggested something like this 3-4 years ago. But now they understand."

Obviously, what epitomises the middle class’ risk-taking mindset is its growing ability to turn into entrepreneurs. No one wants to work for someone; even if they do, they are willing to change jobs every year for more money or other reasons. A joint study by the London School of Business and Babsons College, which surveyed 40 countries that account for 70 per cent of the world’s output and 60 per cent of its population, found that 18 per cent of Indians, in the age group 18-64 years, were engaged in some form of entrepreneurial activity. Although India was ranked seventh, its position was higher than the US, China, Japan, Germany and France. The report stated thatIndian start-ups created 17 million jobs in 2003, the second highest behind China.

People are giving up their jobs to start new ventures; this became a craze during the days of the new economy boom. SudheerKoneru, senior VP, SumTotal Systems, is one example, although he’s back to being a senior manager.Another investment banker I know left an attractive job with GE to start an Internet venture. It flopped, but he kept experimenting with new ideas and is back to working as an investment banker. Government employees and those—like GauthamGopal, a garments exporter—working forPSUs are opting for VRS (voluntary retirement scheme) and starting businesses .

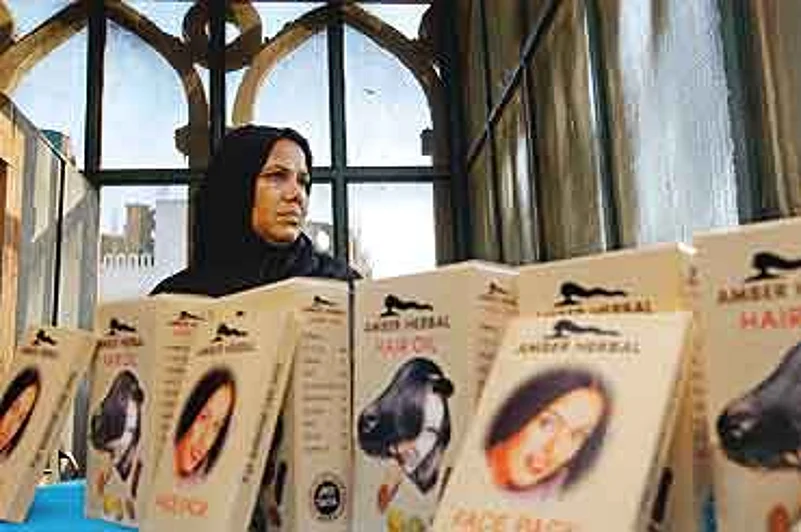

Anisa Begum,age 45, entrepreneur, Delhi

She has been separated twice, was cheated by both her husbands, has four children, and has come up trumps as an entrepreneur. Her herbal products factory was gutted. But she started all over again and plans to sell her wares in the malls.

The same risk-taking sentiments are, in a way, seen in personal lives.Just count the number of women (or men) who are separated, even with kids, but are comfortable with their decisions.Let me take you through this tragic, yet courageous, story of Anisa Begum.At 45, she’s been separated twice, was cheated by both her husbands, has four children, but has resurfaced successfully, both as a mother and as an entrepreneur.Soon after she got married at 16, her husband ran away to Pakistan and divorced her when she was 21."That was the first time I stepped out of the house without a burqa," she remembers while sitting in her run-down, two-room apartment in Batla Chowk near Delhi’s Jamia Millia.A year later, she set up a small embroidery unit at her house, supplied garments to an export house, did a course in poultry farming, became a minority partner in a poultry farm in a village near Noida. She learnt on the job as she had not studied beyond the ninth standard. Years later, she decided to marry again.

"That was the worst decision of my life. My second husband was unemployed, and forbade me to work too," shesays. But when they ran out of money, she defied her husband’swishes to work again "as my children’s education was at stake". She came from a family of hakims and it seemed natural for her to get into herbal products. Business picked up, she caught the attention of government officials who asked her to participate in an exhibition, where her products were soldout. She was referred to the Bharatiya Yuva Shakti Trust, run by the CII, received financial aid of Rs 50,000, which was used to set up a factory in Okhla.In 1996, she won theJRD Tata award for best entrepreneur.

Life seemed good, but who can fight fate? Her factory was gutted in a fire. She says her jealous husband destroyed the evidence required to claim the Rs 3 lakh insurance. "I found the strength to fight back and divorced my second husband." She managed a claim of Rs 85,000 and used it to start all over again. She built a new factory in Bawana (Haryana). "My eldest son runs a restaurant in Japan and my other son wants to become a software professional. Only the daughters are interested in the business," she says. As the muezzin from a mosque calls out for the evening prayers, she quickly added, "I want to sell my products in big malls—Sahara, Ebony and Sab ka Bazaar."

Anisa is the quintessentially neo-middle class. Another one is Meenakshi (name changed), who’s in her mid thirties, separated, lives with her two kids, and doesn’t wish to marry again unless she finds a good guy. "When I took the decision, it was emotionally upsetting, but I was never scared about issues relating to finance or my ability to take care of my kids. I have always been independent and was confident that I’ll be able to do it. I have never cared about society," she says. Or look at Lakshmi (name changed), who works for a marketingMNC and is based in Malaysia. She married at 19, went to Australia as her husband lived there, left him in six months, didn’t have money, somehow managed to come back to India, couldn’t face her parents, and subsequently did crazy things in her professional life.

Her firm had legal issues in Nepal. While handling the crisis, she had to sneak in and out of the country for fear of being arrested. She stayed at non-descript hotels and never told anyone where she was staying. Later, she went to theLTTE-controlled areas in Sri Lanka, where some customers had problems. While meeting them, she was told that a few LTTE people were among the crowd and it could get a little dangerous. She fled the same night, although it was dangerous to do so because of the land mines that separatists had laid along the route to Colombo. She survived and went to Cambodia to handle a similar crisis. "I had no stakes. I wanted to prove myself.Somehow, I thought that nothing would happen to me. Maybe, if I had kids, I wouldn’t have done it," explains Lakshmi, who travels a lot and, while she was based in Bangalore, she never spent more than ten days in a month in the city.

This new crop of middle class is actually willing to go wherever they have to—especially geographically.They are not just Indians, they are transforming themselves into global souls. The IT and the BPO boom have opened up new opportunities for them.Meet Puneet Pushkarna, president (SE Asia operations), Headstrong. Based in California, his work takes him regularly to Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, the Philippines and Australia."My family life is a mess. I missed my daughter’s convocation and my wedding anniversaries. But I enjoy working like this. I feel proud to be some sort of a brand ambassador for India Inc. There are many others who are working like me," he says.

Such souls, as is obvious, may know several cultures but don’t have time for national politics. Even when they have, they are not interested.Lakshmi, who’s never voted, finds politics amusing and funny. Ninaz Kapadia (name changed), 35, a loving mom who’s swift in taking stockmarket-related decisions and runs a successful linen business, says she neither has the time nor the inclination to vote."I’m more aware than normal people. I read the papers and follow the news headlines on TVchannels. But there’s something that makes me reluctant about voting. Maybe, because I know it’s a false choice—what’s there to choose between Sonia and Vajpayee?" she explains and asks to be excused as she has her daughter dressed and has to rush off to a powerpuff theme party (whatever that means).

Ananth Kumar, a BJP MP who’s won all elections from the south Bangalore constituency in the past ten years, differs slightly. "Over 60 per cent of voters in south Bangalore are from the middle class. I think they are still interested in the political process, but their concerns have changed. Ten years ago, they would discuss issues like secularism. Today, they ask questions about development, infrastructure and growth," he says. Infosys’ Nilekani explains how the urban middle class voter is bothered about things that impacts him directly. So, he would be worried about the state of the roads, where he spends hours while commuting. Or the drainage system or the neighbourhood security. "The number of citizen forums who take up such issues is an indicator," says Nilekani.

Slowly, but steadily, the middle class is talking economics. Last week, I went for a panel discussion organised by the economics department of a south Delhi college. I casually asked if the students had leftist leanings, as was the case when I was studying, or believed in market reforms. "Market reforms," pat came the reply. "No one is a leftist any more." As India becomes younger—56 per cent of Indians are below 25 years—the belief in reforms, globalisation, higher economic growth can only increase. And, in this survival-of-the- fittest kind of life, let those who get hurt, remain hurt.

What’s surprising is that many of the die-hard leftists, including politicians, are singing the rightist tune. AdhirChoudhury, the Congress MP from West Bengal, is one of them . There are others who, in their younger days, were members of the Students Federation of India (a CPI(M) wing) or the Democratic Youth Federation of India (another CPI(M) wing). But they have changed colours. Sajal Dasgupta, who owns a software development and consultancy firm that employs over 100 people in Calcutta, exemplifies this breed. "I was an office-bearer of the SFI during my college days in Calcutta.