In Tamil Nadu, for the Sun TV network, political and business interests seem to go hand in hand. The group enjoys virtual monopoly in television and is now taking on print with the purchase of 'Dinakaran'. In Telugu, 'Eenadu' andETV control most of the market. Why do monopolies persist and don't we see healthy competition?

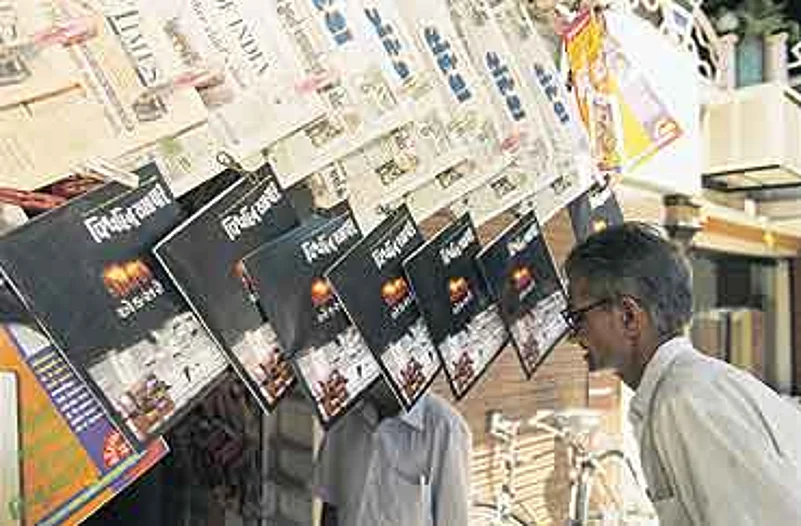

What business person would turn down the chance of operating a monopoly? The trend in English-speaking countries has been towards monopoly in the media. In Australia, two big newspaper chains control 90 per cent of daily circulation in big cities. For the time being, India is relatively fortunate with the kind of newspaper competition you see on the hawkers' stalls in the bus stands in, say, Thiruvananthapuram or Delhi on any morning.

Whenever the topic is FDI in print, there's talk of safeguards and issues of national concern. But wouldn't the presence of foreign players and global capital challenge the complacency of monopolistic mercantile capitalism?

That is probably right. If foreigners start papers, there's an extra voice created. Australia faces this question at the moment. Government has to decide whether to eliminate restrictions on cross-media ownership. And if it does, it will also probably lift restrictions of foreign ownership to try to get some more players into the media business. In India, too, foreign arrivals might provoke vigorous Indian response. Ramoji Rao said one of the reasons for founding Eenadu was to give Telugu speakers in the 1970s a Telugu-owned voice. It was a matter of self-respect for someone who could afford to express his self-respect by starting a newspaper.

You have discussed the connection between democracy and media expansion. But the media does not seem to be representative of demographic realities. In 1999, you had devoted a chapter to the near-total absence of Dalits in Indian newsrooms. Has anything changed?

Almost nothing, so far as I am aware. I'm told, reliably I think, that there is not a single Dalit newsreader or weather person on any television channel. When will we get, say, a national Dalit weekly, doing what the Chicago Defender did for African-Americans from the 1920s to the 1950s? The absence of such a voice is a mark of the political and economic weakness of the Dalit middle class.

In the US and Europe, there are demands on the media to be socially responsible. Why does the Editors Guild in India not seem to have similar concerns? Moreover the Press Council of India seems virtually defunct. Is this not dangerous?

If the national government intends to let the Press Council quietly fade away, that would be a very bad thing. What's needed is a revamped "media council" that would monitor ethics and conduct in the electronic as well as print media. But such a council would be politically difficult to create. Most governments find media matters very hard to deal with because they fear that powerful proprietors will turn their organisations against the government.