The Chandni Chowk constituency, that romantic heart of Purani Dilli, is being fought over by 41 candidates, a bewildering 19 of whom are independents. Running your finger down the list of anonymous names, you pause at Prem Narain from 5/7 (Backside) Roopnagar, Age 51, 12th Std Pass, Total Declared Assets Rs 15,000—the last fact alarming because the deposit of Rs 10,000 is non-refundable to minor pollers.

It is too late to say, 'No! Don't do it!', but still you ring Prem Narain at once, seeking crucial insight: the desperation in the mulk; the realpolitik behind his move. His caller tune is Shailendra's lovely Ajeeb Dastan Hai Yeh. He answers in a rueful, geriatric voice. He tells you he is doing this "for the experience". He is a gent's tailor. He has never stood in any kind of election before. He has no special grouse nor ambition. You try to sense whether he has been put up as a vote-spoiler, but in his own estimate he won't poll more than 300 votes. You try to push him for a manifesto, which he supplies, after some thought: "Hum bhi kuchh kar sakte hain (I too can be something)."

Disarmed, you wish him luck and hang up. You picture candidate Prem Narain at his sewing machine, five days before general election, an inchi tape around his neck, a cup of tea by his side, singing Ajeeb Dastan Hai Yeh.

***

Delimitation has utterly transformed Chandni Chowk. It was the smallest Delhi constituency at 3.4 lakh voters. Now, chunks from eastern and outer Delhi have been added, tripling the electorate. The Muslim population, a third of the demographic in 2004, is down to a fifth or less. Hence, you conclude that independent candidate Mohammed Shafiq of Bahar Wali Gali, Chatta Lal Mian, Daryaganj, in the old walled city, might offer insight. You track him down, penetrating deep into Bhaijan Market, turning left at the peepal ka ped, past the first cut, which is Pahad Wali Gali, into the next cut, which is Bahar Wali Gali, into a tenement with a crowd of coloured doors, where Shafiq's is the pink one.

He emerges freshly bathed in a white bush-shirt, white trousers, sandals, and a thick black moustache. He is annoyed with the state of affairs. There is no water in the area; the schools are in such a state that when children come home you think they have returned from a jungle. "Badi qorma-biriyani waali baat ki thi," he says of the incumbent MP, Kapil Sibal of the Congress, "lekin jeetne ke baad mooh tak nahin dikhaya. Musalmanon ke liye kuchh nahin kiya (He made great promises, won, and vanished. He did nothing for Muslims)." But his principal contempt is reserved for Shoaib Iqbal, the sitting MLA; and it is to battle Shoaib Iqbal that he is taking this step.

Shoaib Iqbal, a donnish local presence, is from Ram Vilas Paswan's Lok Janshakti Party. As in 2004, he opted out of these elections at the 11th hour. Subsequently, his brother and nephew became chairman and deputy of an influential municipal committee. In Chandni Chowk, rumours abound of deals. Shoaib Iqbal: this is sufficient insight. For, upon taking leave of candidate Shafiq and ringing candidate Bashiruddin, who, by coincidence is currently aboard a rickshaw a minute away from Golcha Cinema towards which you too happen to be walking, it is confirmed that the chief cause driving Muslim independents to contest is MLA Shoaib Iqbal.

***

No sooner have you got on to the rickshaw with Candidate Bashiruddin, a delightful slip of a 63-year-old who bagged 55 votes in the assembly elections last year, than he thrusts a yellow cyclostyled sheet of Urdu into your hand. It is a polemic against Shoaib Iqbal. It is the sum amount of Bashiruddin's campaign. "Qurbani ya saudebaazi?" it asks, "Jawab do, Shoaib Iqbal." (Sacrifice or horse-trading? Answer us, Shoaib Iqbal. ) If you truly cared about the qaum, Shoaib saab, it says, you would have supported a Muslim candidate: Haji Mustaqeem of the Bahujan Samaj Party. But no. The same Congress which you yourself said was responsible for Gujarat, for Babri, for Batla House, you ask the qaum to elect that same Congress.

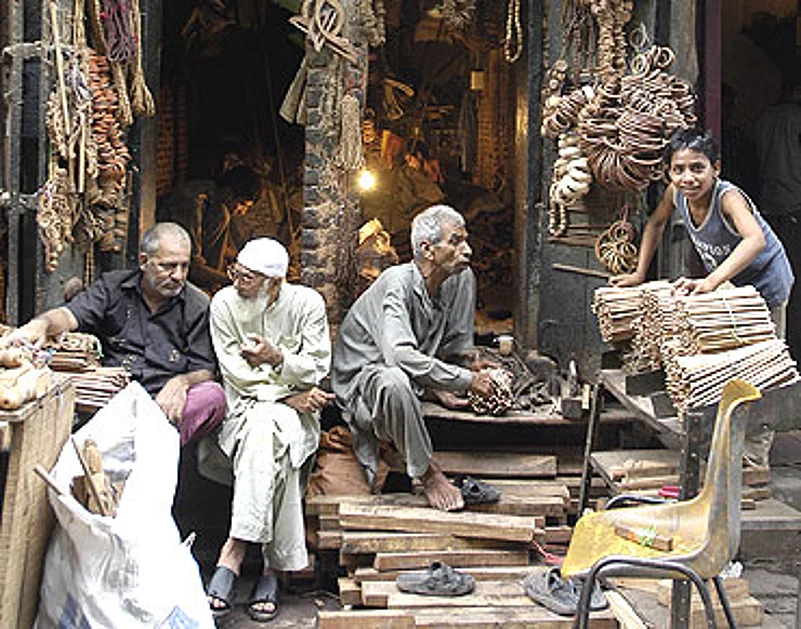

Sugar control vies with wood in Ballimaran

Our rickshaw arrives at Jama Masjid, blazing red in mid-day May. And here, with a clever sparkle, candidate Bashiruddin instructs a youngster to go to the mosque, then the madrassa, and hand these cyclostyled sheets to those emerging from prayer. We talk briefly of his life and times, of his fall from nawabi, his revival of a derelict mosque, his friendship with the Shahi Imam of Jama Masjid, who had earlier controversially called for Muslims to unite under a single political party; and of his travails, which he relishes. He is running his election campaign on a budget of Rs 80,000, of which Rs 30,000 are donations gathered at his jalsas. For his jalsas, he giggles, are great fun. "Main chatni chataa chataa kar baat karta hoon (I make them spicy)." With that, candidate Bashiruddin disappears up the street, to organise the permission slip for his jalsa in the evening.

***

You soon come to appreciate the power of the permission slip, when you locate, at last, the multi-layered address that is Nooruddin Park, Beri Wala Bagh, Bara Hindu Rao, Azad Market Road, where the BSP's Haji Mohammed Mustaqeem aka Ballo Bhai is to hold a public meeting. Ballo Bhai is an influential Quresh who runs a lucrative mutton export business, and the BSP is the up-and-coming party, a fair contender via its appeal to the lower castes, and now, through Ballo Bhai, to Muslims, who together make up almost half the constituency. But on a patch of bare earth on this cacophonous intersection there are only empty chairs, and a platform about to be dismantled. The young man in the white salwar kameez, Ballo Bhai's nephew, tells you amid several purges of paan spit that the event has been cancelled. The permission slip was in his younger brother's pocket; and the boy left for Kashmir with the slip still in his pocket. "Bade gusse mein hain Ballo Bhai (Ballo Bhai is very angry)," he adds, somewhat boastfully.

***

You move up the scale, from the irrelevant independent, past the new challenger, to the old force. They do things differently here, you think. For shortly after contacting them, e-mails from the Sibal Campaign have landed in your inbox, the first of them titled: 'Vijendra Aur Unki Patni Par Gambhir Aarop (Serious Allegation Against Vijendra And Wife)'. Vijendra here is Gupta, the arch-rival from the BJP with whom Sibal has traded accusations and lawsuits liberally over the past weeks.

Notwithstanding the increase in Chandni Chowk's Hindu trader community population, the feeling is that the game is Sibal's. In 2004, he polled 71 per cent of the vote to BJP's 27. The Congress won six of the seven Delhi seats, and also triumphed in the area in last year's assembly elections.

The itineraries dispatched by the Sibal campaign indicate that he begins campaigning at seven every morning and finishes at 10 at night. In the maze of events, you zero in on a Saturday night meeting at Jama Masjid. It is to be graced by the main man, MLA Shoaib Iqbal. There, walking through the mad crowd and fights, chaat stalls and special thalis, temples, gurudwaras and signboards of Chandni Chowk, between the crate-laden rickshaw lane of Lajpat Rai market, past mounds of tomatoes and potatoes, and through the old Cotton Market exploding with gaudy blankets, you emerge from behind the magnificence of Jama Masjid, pale in the yellow night light, into the fluorescent street, and in a gathering of maybe 500. You take a seat next to an impoverished cripple holding a Kapil Sibal flyer, the reverse of which supplies the season's IPL schedule.

A man begins with a praise song for Kapil Sibal; and then, a pink-shirted Aligarhi produces a poem that segues into a thunderous speech. "Elaan-e-jung hai yeh faasist taaqat ke khilaf (This is a call to arms against fascist forces)," he declares. His voice gains strength with every line, reaching a crescendo with an apocalyptical vision of a BJP victory: "Hawa takrayega baadalon se. Pani nahin zehar barsega (The wind will clash with the clouds. It will rain not water but poison)."

Mr Sibal, only 15 minutes late, arrives to chanting and takes the mike to silence. He appears tired. He warns of an India with Advani and Modi at the helm; commits to make Gujarat India rather than India Gujarat; he points to a child in the crowd, and asks what about her education, her future under Advani and Modi?

Just then, however, he is interrupted rudely by an extended volley of fireworks and a gang of aggressive sloganeers: Shoaib Iqbal has arrived! Mr Sibal is not pleased. He requests silence from Shoaib's supporters. Shoaib climbs hero-like on to the stage, and at the end of the address, a humongous tricoloured garland takes both prosperously built gents in its embrace.

When Shoaib Iqbal makes his address, you see why he has been roped in as the vote-puller. Under a puff of filmy hair, he reiterates his fight against communal forces and his sacrifice for the qaum in this regard. He speaks urgently, conveying the impression that you missed a word at your own peril. He extracts a promise from the crowds that not a single vote shall go to the BJP or, for that matter, the BSP, for they are liable to join forces with the BJP. He draws great cheers, and applause rings in from the elders in the crumbling balconies across.

And shortly after, fear having been sold, the blackmail complete, the gathering dissipates.

You ask an old-timer when the BJP will campaign here. Never, he replies. But they are out there somewhere in the dark night, peddling an opposite fear, issuing a contrary blackmail, and you think to chase it.

Another time.

(Rahul Bhattacharya is the author of the acclaimed book, 'Pundits from Pakistan'. He is currently working on a book on Guyana.)